West Africa. Hezbollah. Financing to the Party of God.

The Lebanese movement relies on a mafia-like, opaque system

rooted in the Shiite diaspora, which also uses the laundering of

proceeds from illicit trafficking networks to reach Shiite

neighbourhoods in Beirut.

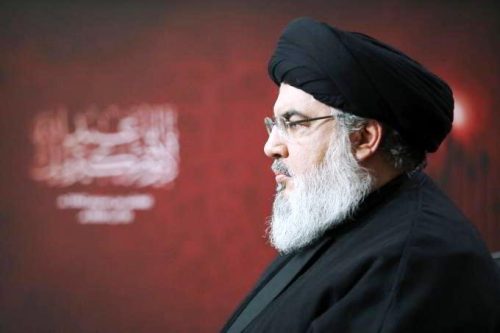

In Abidjan, especially around the al-Mahdi Mosque in the Shiite neighbourhood of Marcory, many have been in mourning for days after the killing, last September 27, of the charismatic leader of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, hit by 80 anti-bunker bombs, dropped by the Israeli army on the headquarters of the Lebanese Shiite movement in Dahieh, in the south of Beirut. In Ivory Coast, 100 thousand Lebanese live, 80% of whom are Shiite Muslims. But since the 1980s, Hezbollah has had ramifications in West Africa.

On 27 September last year, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed by the Israeli army at the headquarters of the Lebanese Shiite movement in Dahieh, south of Beirut. Shutterstock/mohammad kassir

While the emigration of Lebanese Maronite businessmen to the continent has been documented since 1910, the stable presence of a Shiite community, particularly in Guinea and Ivory Coast, began just when Hezbollah was born in Lebanon. Not only that, the Lebanese Shiite diaspora has established solid ties with Beirut, as often happens among migrants who maintain strong emotional roots in their homeland. This is why political scientist Benedict Anderson called them “long-distance nationalists.” And so, the support for Hezbollah from the Lebanese Shiite diaspora in West Africa, not numerous but rich, has never been lacking. Indeed, it has grown over the years.

Lines of credit from the mosques

The lines of credit began, as often happens, first of all from the mosques frequented by the Shiite community in Abidjan, such as al-Zahra, and from religious centres, such as al-Ghadir, also in the economic capital of the Ivory Coast. From here, millions of dollars are sent every year, simply donated as ritual alms, or zakat, towards Beirut. In 2009, during the presidency of Laurent Gbagbo, the imam of this mosque, Abdul Kobeissi, was arrested, convicted and expelled to Beirut after being accused, also by the United States and Israel, of financing Hezbollah. “Everything is allowed for a good cause, which can be the survival of the movement, the resistance against Israel, the military support for Bashar al-Assad in Syria, the training of Huthi militiamen in Yemen.

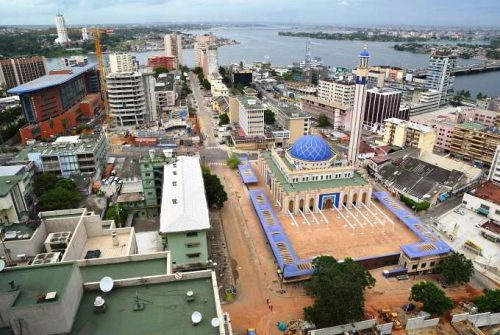

Abidjan. Great Mosque. In Ivory Coast, 100 thousand Lebanese live, 80% of whom are Shiite Muslims. CC BY 3.0/Citizen59

These are all valid reasons to continue financing Hezbollah, even from so far away,” explained Lebanese analyst Maya Khadra.But these ties with Lebanon also guarantee many advantages to the Shiites in Ivory Coast. For example, when in 2004 there were strong tensions between Paris and Abidjan, with the attacks against the French military presence as part of the United Nations Operation in Ivory Coast (UNOCI), it was precisely the diaspora close to Hezbollah that secured the assets of the Lebanese community in the country.On the other hand, aid arriving in Beirut from West African countries has been growing, even after the economic crisis of 2019, with the devaluation of the Lebanese lira and the explosion of the port of Beirut in 2020. In particular, a large part of the economy of the city of Tyre, hit by Israeli bombings in recent weeks, in southern Lebanon, is supported by remittances from migrants in Ivory Coast. So much so that one of the streets in the village of Zrarieh has been renamed “Abidjan Street”.

Hezbollah policy

But Hezbollah did not stop there, it soon began to engage in politics in West Africa. This happened, for example, with the military support that affiliates of the Lebanese Shiite movement gave to the Polisario Front, which is fighting for the liberation of Western Sahara from Morocco, alongside members of the Iranian al-Quds militias. Not only that.

US Treasury Department reports confirm that 30% of the cocaine trafficking through Africa to Europe passes through the hands of Hezbollah affiliates. Shutterstock/Fuss Sergey

Many analysts have reconstructed the role played by members of the group in the 2023 coup in Niger. “The geographical presence of Hezbollah in West Africa was encouraged by logistical reasons: the control of drug, diamond, wood and weapons trafficking. In particular, drug trafficking starts in Latin America, especially from Colombia, Venezuela and Mexico, and then passes through the countries of West Africa from where their illicit marketing and distribution in Europe begins. These networks have seen an active role of members of the Lebanese Shiite movement”, added Maya Khadra. Reports from the US Treasury Department also confirmed that 30% of the cocaine traffic that passes through Africa to reach Europe passes through the hands of Hezbollah affiliates.

The effects of the economic crisis

Yet even the Shiites in the West African diaspora have had to deal with the serious consequences that the economic crisis has had on the Lebanese, for example on the methods of financing Hezbollah. Since the United States included the Lebanese Shiite movement in its list of terrorist organizations – imposing sanctions on private supporters, companies and charities that have ties to the group – and following the measure taken by Lebanese banks that have capped the withdrawal of money at a few hundred euros, the old methods of getting the money to its destination have returned. “Money laundering, which is reused to finance Hezbollah, is often transported in the suitcases of Lebanese passengers who take commercial flights,” Maya Khadra explained.

Aerial view of Beirut city and the port. “Money laundering to finance Hezbollah is often transported in Lebanese passengers’ suitcases on flights.” Shutterstock/mohamed.m1

This happened, for example, in 2003 when between 2 and 3 million dollars were found in the suitcases of one of the passengers of the Boeing 727-200, which crashed in Cotonou, Benin. The same thing happened to two Lebanese-Guinean businessmen, Ali Saadé and Ibrahim Taher, accused of “money laundering and financing terrorist groups,” arrested while trying to bribe customs personnel at Conakry airport, to travel with bags full of dollars, intended, according to Washington, to finance the activities of a Hezbollah affiliate in Lebanon, Kassem Tajideen. And so, the Lebanese movement, in addition to the funding coming from Tehran, relies on a mafia-like and opaque system in West Africa, rooted in the Shiite diaspora, made more fragile by the economic crisis gripping the Lebanese, which also uses the laundering of the proceeds of illicit trafficking networks to reach the Shiite neighbourhoods of Beirut. (Open Photo: Hezbollah flags painted over cracked concrete wall.Shutterstock/sameer madhukar chogale)

Giuseppe Acconcia