“We are the ‘most beautiful’ of all”.

The cult of physical beauty is most important. The rules of aesthetics are followed by the entire group.

Gently but firmly, the mothers try to shape the physiognomy of the new-born child in the hope of affecting the collective appearance of the group. From birth, the head of the child is delicately squeezed between the hands and the nostrils are compressed.

The Bororo believe they are the most beautiful people in the world.

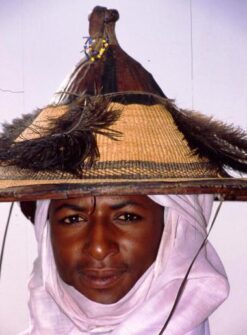

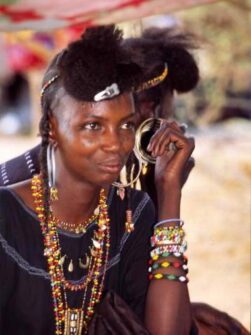

The man is tall and slender with a straight nose, large eyes, white teeth and a high forehead. These are the rules of beauty for the male nomad. The woman also has soft and gentle lines and wants to have a concave spine and lengthened breasts. She wears her hair in the form of a bun plaited on her forehead. The scars on her face and the sides of her mouth denote the clan she belongs to and protect her from evil spirits. Her jewels and ornaments make her even more good looking. For her, beauty represents the joy of life.

The social position enjoyed by the woman within the family renders her tranquil. She has the same status as the husband: she may share her man with three other wives but she may easily abandon him.

The young Bororo spend much of their time taking care of their bodies. They adorn themselves with earrings and multi-coloured necklaces and cover their eyes with a blue veil. They live as young people up to the age of sixteen. When a man asks for a young woman as his wife, he must accompany his request with a gourd full of milk: if he is accepted by the family of the girl, the future spouse must offer his in-laws three Zebu cattle for the great marriage feast. Every palio, a word denoting a single Bororo, gives the greatest attention to respecting the norms of behaviour handed down from father to son: strength, courage, pride, honesty. When he goes against them he becomes a pulaku (meaning ‘you are outside’, you have gone beyond the norms of the fathers and you must therefore leave). Another serious offence is that of the septundum, lacking respect for the wife or not satisfying her desires, including her loving advances.

“If her heart is already far from you, a mother may say to her son, you must not keep her because her sorrow will also become yours. Her beauty will fade. It is better that others should see her while she is beautiful rather than have her become unhappy staying with you”.

According to the Bororo, man and woman are like two poles that naturally attract each other. When she is ‘ready’, when she is neither pregnant nor breast-feeding her child and finds someone who attracts her, she must immediately halt, even if her herd is moving with the entire group. She stops in order to be with her young man who will never call her by name since this is prohibited by tradition. ‘The one you love, you must respect’, they say. One form of respect is not to show love openly. This is really a matter of avoiding the semteende, ‘the shame’, that strikes whoever breaks the taboo.

The Bororo woman is, however, free and independent. She has no regard for virginity and may reject the man her mother and father offer as her future husband. If her husband is unfaithful, the demands of culture determine that she is in no way faithful since this would be unjust. (F.M.)