USA/Africa. Uncertain Future.

Donald Trump as President of the United States could have important consequences for Africa. These could include higher trade tariffs, less development aid and less political conditionality on human rights. However, Trump’s unpredictable nature may hold surprises

for Africans.

According to Afreximbank’s 2024 Trade Report, the United States has become a secondary trading partner, accounting for only 8% of Africa’s exports and less than 5% of its imports, well behind China (20% of Africa’s exports and 16% of its imports), the European Union (21.4% of Africa’s imports and over 30% of its exports) and the Middle East (10.8% of Africa’s exports and 8.2% of its imports).

Trump’s first term saw a tough trade policy. The Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which exempts 1,800 products from 32 countries from tariffs, saw US imports from Africa peak at under $10bn a year, down from $66bn in 2008.

The United States accounts for only 8% of Africa’s exports and less than 5% of its imports. 123rf

This trend is likely to continue, with everyone expecting another tariff-heavy approach. During his previous administration, Trump said AGOA would not be renewed when it expires in 2025.

As a result, African exporters are likely to sell less in the US market. South African exporters of fruit and automotive components are affected, as are Kenyan, Nigerian and Ghanaian textile producers.

Nevertheless, some African exporters expect Trump’s transactional pragmatism to prevail. After all, the results of his Prosper Africa initiative during his first term were not insignificant.

It closed 2,500 deals in 49 countries worth $120bn. Optimists hope that as a deal-oriented leader, President Trump could preserve AGOA, provided some changes are made.

Analysts say that if the US is serious about countering China’s growing economic influence in Africa, it will need to maintain some level of partnership. In this regard, Trump may be tempted to implement Joe Biden’s project to invest in the Lobito Corridor in Angola, so that the railway line can transport critical raw minerals from Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the Atlantic Ocean for export to the US.

Pundits are also predicting possible cuts to US aid to Africa, which amounts to about $8 billion a year. Trump’s first administration proposed slashing foreign aid worldwide. But the Democrats, who controlled the Senate at the time, opposed the cuts. Now, with Republicans holding a majority in both houses, no one can stop Trump from making cuts if he wants to.

The Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi was among the first to congratulate Donald Trump on his victory. Photo: Simon Walker / N.10 Downing Street

In any case, many African leaders seem pleased with Trump’s victory. His victory was immediately congratulated by Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Ethiopia’s Abiy Ahmed, Nigeria’s Bola Tinubu and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa. The King of Morocco, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi, his Ivorian counterpart Alassane Ouattara, Chad’s President Mahamat Idriss Deby and Senegal’s new leader Bassirou Diomaye Faye also rushed to congratulate the new American president.

Trump’s victory was hailed also in the Sahel, where military leaders expect that he will focus less on democracy and human rights. The leaders of the Sahel Alliance formed by Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger believe indeed that Trump shares with them the same sovereigntist ideology. President Emmerson Mnangagwa of Zimbabwe who faced US sanctions in the past also praised Trump’s triumph, describing him as a leader who “speaks for the people” while Paul Kagame of Rwanda celebrated his “historic and decisive” victory while stressing his opposition to any interference. King Mohamed VI reminded that during his first mandate, Trump recognized Morocco’s claim over Western Sahara, (in exchange for the recognition of Israel).

But protocol aside, the future relationship between the US and several key countries remains uncertain. South Africa, which filed a complaint with the International Court of Justice against Israel for genocide in Gaza in December 2023, may face difficulties given Trump’s staunch support for Netanyahu and his cabinet of hawks.

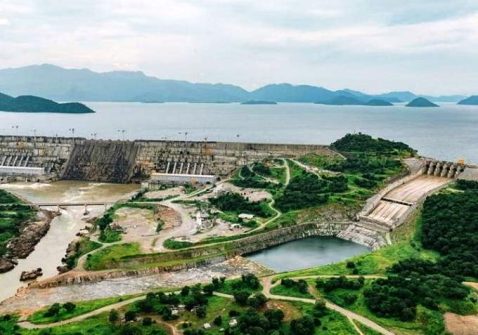

Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam aerial view. Trump appears to have sided with Cairo on the issue of the Renaissance Dam, which Ethiopia is building on the Blue Nile. Photo: Prime Minister Office Ethiopia

During Trump’s first term, contradictory signals were sent to Ethiopia. On the one hand, Trump’s former special envoy, Peter Pham, insisted on the importance of recognising Ethiopia’s legitimate interest in access to the sea, and Addis Ababa announced the signing of a memorandum of understanding with the breakaway state of Somaliland to build a port there. On the other hand, diplomats stress Trump’s desire not to antagonise Egypt by showing too much sympathy for Ethiopia or Somaliland. Indeed, Trump appears to have sided with Cairo on the issue of the Renaissance Dam, which Ethiopia is building on the Blue Nile and which angers Egypt because it could deprive it of much-needed water.

In 2020, Trump said Egypt would not be able to live with the dam and might “blow it up”.

Apart from issues such as access to critical minerals and security, Trump is not expected to spend much time in Africa during his second term. He has never travelled to Africa as president. This could mean that the military’s U.S. Africa Command, or AFRICOM, will continue to be the main face of U.S. policy on the continent.

US Africa Command, Gen. Michael Langley. Under the Trump administration, U.S. Africa Command, or AFRICOM, will remain the main face of U.S. policy on the continent. Photo: Jeremiah Meaney

One concern, however, could prompt Trump to guarantee some American presence on the continent: China. Indeed, Trump’s former assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Tibor Nagy, is convinced that the new Republican administration will not neglect Africa because it sees China as a threat to US interests there.

An isolationist “America First” agenda that ignores Africa would provide an opportunity for Beijing to expand further into the continent, predicts Yun Sun, director of the China Programme at the Stimson Centre. According to Christopher Isike, professor of African studies at the University of Pretoria, Trump’s disregard for Africa could also encourage African countries to pursue stronger trade and relations with Asia and the Middle East.

On the security side, Trump’s isolationism should mean less interference than during the Biden administration. During his first term, Trump ordered the withdrawal of American troops from Somalia where they fought al-Shabab jihadists. Yet, Donald Trump can also be unpredictable. Reports of collusions between Iran-backed Yemen Houthis and al-Shabab, which increase the risk of attacks on American vessels may change his attitude.

With his relationship with Vladimir Putin less strained than under the Biden administration,

During his election campaign, Trump promised to deport more than a million illegal immigrants from the US. 123rf

Donald Trump could also create synergies between the two superpowers to combat the scourge of jihadism. The Russians might welcome such an initiative if they acknowledge that even if they have gained influence in the Sahel, they have not managed to eliminate the Islamist threat and that they might need US intelligence to achieve this goal.

African states should also be prepared for a new situation at the UN, where Trump may not feel bound by Biden’s commitment to support the creation of two permanent seats for Africa on the Security Council. Afro-US relations are also likely to be influenced by Trump’s desire to achieve success on illegal immigration. During his election campaign, he promised to deport more than a million illegal immigrants from the US. Africa is concerned: according to US Customs and Border Protection, 58,000 African migrants were apprehended at the US-Mexico border in 2023, four times more than the previous year. Concerns are particularly high in Nairobi, Khartoum, Abuja, Asmara, Dar-es-Salaam and Kinshasa. (Illustration: Pixabay)

François Misser