Uruguay. A Buffer State.

The country is preparing for the next presidential elections which will be held on October 27th. The Frente Amplio is currently ahead in the polls. We retrace the political and economic path of this South American country.

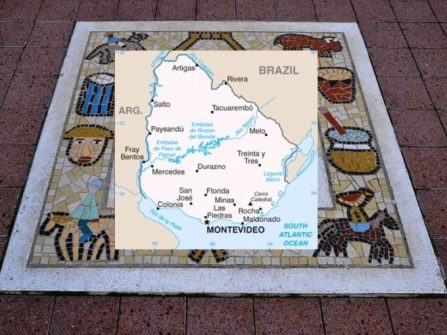

Located on the Atlantic side of the Southern Cone, and second in extension only to Suriname, Uruguay is the smallest country in South America with a surface area of 176,215 thousand km2. Its size also appears reduced considering that the country is nestled between the two South American giants, Argentina and Brazil, from which it obtained independence in 1828 and with which it shares borders of 580 km to the west and 1,068 km to the east, with the remaining 660 km of coast washed by the Atlantic Ocean.

From a morphological point of view, the country is flat on which, at times, the cuchillas, low hill systems rise, rarely exceeding 500 m, and is crossed from East to West by two large rivers, the Uruguay and the Río Negro, its tributary, whose basin occupies approximately half of the state’s territory. Other tributaries of Uruguay are the Cuareim and the Queguay Grande; the Río Negro, in turn, receives the Tacuarembó and the Yi. From a historical point of view, Uruguay represents an exception within the South American continent since, unlike neighbouring countries, it has not undergone the experience of long dictatorial periods, except that which occurred from 1973 to 1984.

This has allowed it to develop, over the years, a democratic path that has led authoritative observers to define the country as the “Switzerland of Latin America”.

José Pablo Torcuato Batlle was the president of Uruguay for the Colorado Party for two terms: from 1903 to 1907 and from 1911 to 1915. Photo Archive.

The roots of the renowned economic prosperity and political stability that existed until almost the middle of the last century can be found in batillismo, an experiment implemented by then President Josè Batlle who managed to build a state free from the pressures of territorial caudillos, open both to modernization and industrialisation and capable of meeting the demands of the population of Montevideo and those of the nascent working class who, together, formed the basis of the interclass social bloc that merged into the Colorado Party. Not only from a political but also from a social point of view, Uruguay is unique since it was the first country in the area to admit divorce even at the sole will of the wife in 1923, to extend suffrage to women in 1927 and to found a truly secular state, equipped with an advanced welfare state system. These were factors which in those years made it become a model for avid supporters of liberalism.Overall, the system took shape as the unprecedented democratic version of an interventionist state, led by a charismatic leader and structured on a two-party system, the Colorados as the expression of the city bourgeoisie and the Masonic lodges, and the Blancos of agrarian inspiration and Catholic brand, whose alternation characterized Uruguayan political life.

The 1960s began to overshadow that period of splendour that had characterized Uruguay up to that point. The economy began to be suffocated by tremendous inflation which reached 40%, resulting in a high level of social unrest which translated into strikes and student mobilisations. It was in this phase (already in the two-year period 1958-1959) that for the first time in ninety years, the Blancos took back the reins of the country’s government and, in order to face the growing economic disaster, agreed with the IMF on a series of liberalist measures that, promptly adopted, consisted mainly in the reduction of credit and public spending and in the downsizing of the active role of the State. These measures, however, contrary to expectations, worsened the economic situation to the point of generating a process of unification of different social segments – such as the working class and students –

who aspired to obtain political representation that

differed from that of the two parallel parties and was historically

convergent in the government of the country.

It is in the described panorama of irritation and discouragement due to the insensitivity of a political class now in disarray and the obstinacy of the strong powers, that a group of politically prepared and determined people sanctioned the birth of the Tupamaros Nacional Liberation Movement in 1962 (MLN), among whose exponents was the future President Pepe Mujica. The Movement quickly managed to involve and attract students and intellectuals, as well as the most sensitive sections of the workers’ movement into its ranks and radicalized its work to the point of accentuating the breakdown of the political balance already tested by the crisis. In 1967, the Colorados returned to power and applied a bloody repressive policy which, contrary to predictions, contributed to increasing guerrilla actions in urban areas. Thus it was that from 1973 onwards the country’s democracy was channelled into a narrow bottleneck. The political forces represented in parliament, with the exception of the Frente Amplio – a movement that had entered the scene in 1967 bringing together the democratic and progressive forces and supported by the MLN – agreed on the suspension of individual rights and on the declaration of a state of war, entrusting, for the first time in Uruguay, the defence of national sovereignty to the armed forces. A Consejo de Seguridad Nacional was also established made up of soldiers and civilians which worked to suspend political activities with the closure of parliament and traditional parties and implemented ferocious repression with arrests and deportations.

Parade of the army of Uruguay. In 1967, for the first time in Uruguay, the political parties entrusted the defence of national sovereignty to the armed forces. Shutterstock/ Ceswal

Even the military, obviously, relied on liberalist recipes to deal with economic imbalances, significantly reducing the role of the State with the aim of reinvigorating demand and market forces, aiming mainly at relaunching exports in the agri-food sector. These manoeuvres, however, which had very heavy costs in terms of the real economy, did not have the desired effect; on the contrary, they led the country towards a terrible and burdensome indebtedness, exposing it in 1984 to a foreign debt four times greater than the total exports the military junta had aimed for.

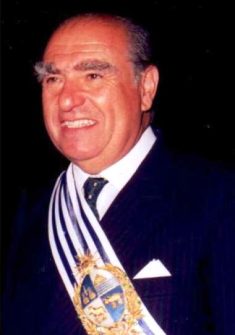

Julio María Sanguinetti Coirolo was president of Uruguay from 1985 to 1990 and again from 1995 to 2000. He was the first democratically elected president after twelve years of military dictatorship.

CC BY-SA 3.0/ Agmontesdeoca

This unfortunate dictatorial parenthesis ended, at least formally, in 1984 when the presidential elections placed the civilian Julio M. Sanguinetti at the helm of the country. A member of the Colorado party, he was, moreover, reluctant to free himself from the protection of the army, benefiting on the contrary from its protection to repress the strikes and mass mobilizations that again affected the country in those years.A few years later, in 1989, the MNL returned to legality by participating – as the MPP – in the Frente Amplio which with Tabaré Vázquez would win the administrative elections in the capital in 1994 and, subsequently, the presidential election in 2004. This last date marked the end of the Uruguayan bipartisanship that was mainly responsible for the economic crisis and the military coup. (Open Photo: Uruguay Flag. 123rf)

(F.R.)