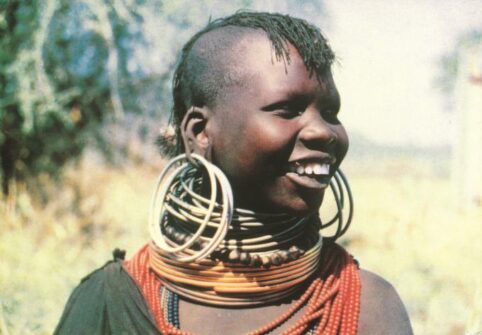

Uganda. Ekipeyos. The prayer of the elders.

Stricken by adversity a Karimojong man, a member of an ethnic group of northern Uganda, does not keep it to himself but renders the entire community participants in his sorrow. Above all, he entrusts himself to the prayers of the elders who come to his aid with a traditional community celebration called the ekipeyos.

The Ekipeyos is a traditional ceremony consisting in the slaughter of a steer to celebrate and honour the elders gathered for the traditional assembly (akiriket) or to render homage to one’s own father or mother, one’s father or mother-in-law. On other occasions, the Ekipeyos takes on a deeper, more religious meaning, becoming an invitation to the elders to pray, during their assembly, for a particular member of the community who is in difficulty.

When an individual or an entire family is stricken by adversity, sickness or death, when their flocks become a cause for deep concern or their harvest is totally inadequate, the Karimojong can do nothing but recognise and accept their impotence and turn to God to free them from their troubles.However, the Karimojong man will never address God by himself. His strong feeling of belonging to a group or a people and the unlimited confidence he has in the efficacy of the prayers of the elders move him to share his troubles with the entire community and to seek the intervention of the elders that they may be intermediaries between himself and the divinity. With this in mind, he visits the elders of his area one by one and explains his problems to them.

The ox for the sacrifice

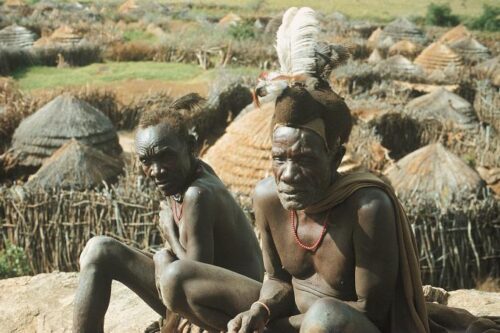

On the established day, the elders go to the village of the person seeking their intercession who meets them in front of the corral where he has his cattle. Only men who have been initiated may participate in this ceremony. All those present sit on the ground in a circle at the centre of which is the ox chosen for the sacrifice. When they are all in their places, the person requesting the prayers stands, holding the spear in his hand and with cautious gestures he approaches the victim. With a lightning-fast and extremely precise blow of the spear, he despatches the ox which falls to the ground.

While those appointed collect the blood in special vessels, an elder (ekasikout) approaches the animal and, with a few precise strokes of the spear, opens its abdomen and extracts the stomach; taking some of its contents, he approaches the man who requested and organised the ceremony and covers his entire body with the viscous material taken from the stomach of the ox. He then repeats the operation for the male members of the unfortunate family and all those present.

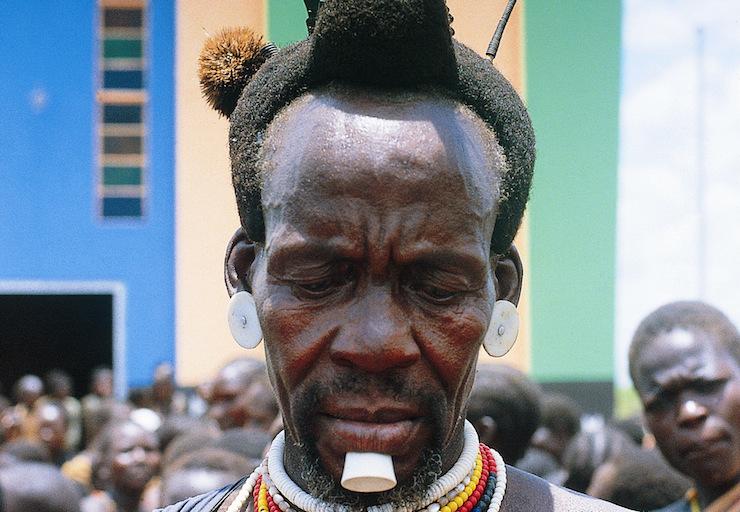

Meanwhile, a young man brings a pipe and fills it with tobacco. Another lights it by placing on it some coals from a fire that has been lit in a corner of the compound. Once the pipe is prepared, the young men hand it to the elders who pass it from one to the other for ritual smoking.

A piece of flesh is then taken from below the anus of the beast (elamacar), reserved for the elders, and the servants quickly cut it into four parts. The elder presiding over the rite turns to two young men saying: “take this meat and put it on the fire”.

They carry out these orders and when the meat is sufficiently roasted, they remove it from the fire and hand it to the two most esteemed elders at the assembly who are seated in the centre of the group. These two take the four pieces of meat and give a portion to each of their two co-elders sitting beside them.

When the elders have finished eating the elamacar, those responsible hand them vessels (ngwito) full of milk. They taste it and spray some of it into the vessel used to collect the blood of the slaughtered animal. This is the traditional form of blessing and reconciliation (akimwar).

At this point, the elders call the one who has asked them to pray and tell him: “gather all your people together. Come and sit down; we will now supplicate God”. All the male members of the family gather close to elders and crouch on the ground close to the pot of blood and milk, in front of the whole assembly.

One of the more elderly men gets up from his place and begins the prayer of exorcism (akigat): “O you, a being who are evil for the cattle, for men, for this corral and this village! You, evil being, leave, get out, go far away!” To convince the assembly even more as to the efficacy of his exorcism, he directly addresses it saying: “Has the evil spirit not gone away yet?” All those present, with a very loud vocal burst, accompanied by hand gestures answer: “It has gone away, it has gone away!”

The verbal tense used in this dialogue between the elder and the assembly: the past perfect, a tense that expressed an action already finished. He is praying for the liberation from adversity that has brought down a family and now he speaks of a past experience, of something no longer present. This is the most tangible demonstration of the unlimited trust the people place in the prayer of their elders.

Using the same tone of voice, the elder continues: “Will the grain not sprout? Has it not already sprouted?” Those present respond: “Alomut!”, “It has sprouted!” “Have the cattle not come back in the evening?” “They have come back!”

Having finished the dialogue with the assembly, the elder continues speaking, using formulas of swearing and exorcism unaltered for centuries, about the presence of the Karimojong in the region, their riches and their power: “The Karimojong are present; the Ngimoru (class in power) are present; the Ngigetei (the class below the one in power) are present; the Ngimiryo (children of the Ngigetei) are present”, etc.

The akigat is a form of prayer that is truly communitarian. All those present may indeed suggest, after the imprecation formulas, their own needs and desires to the presiding elder; he interprets them and proposes them to the assembly. For example, a boy may ask the elders and the assembly to pray for him as he has lost a cow. “Will the cow lost by this boy — the elder intones — not reappear in the evening?” And the people respond: “It has been found, it has already reappeared!”

The final banquet

When the prayers are over, those taking part in the ceremony begin the closing banquet. The meat of the ox is distributed to all present, always giving precedence to the most elderly. The same is done with the mixture of milk and blood: the first to drink are the elders Ngimoru (the class in power) and then the others in descending order.

The assembly becomes enlivened and everybody becomes busy with their portions of meat that they cut with their spears or with an egolu, a round knife held in the right hand.

By the time people disperse to go to their homes, the sun is already going down. The only person who remains in the corral is the person who asked for the prayers, convinced of the effectiveness of the mediation of the elders. He has again found peace and confidence in the future: “I am very happy and satisfied! God will help me and free me from all my troubles!” The people going to their homes are also similarly convinced and repeat to themselves: “God has heard the prayers of the elders!” (A.P.)