Togo. A Voodoo is born to us.

Among the waci (a name that means ‘the souls of our ancestors dwell here’) of southern Togo, the birth of a child is seen as a precious gift, a sign of divine blessings. We now consider the breech delivery.

Unusual births, ones that are so difficult that they endanger the life of the mother or the child, are placed in the context of offences committed by the parents against the family and society. These are punished by the voodoo, the supernatural powers used by God to intervene indirectly in the affairs of the world. This is why the birth of twins, albinos, babies born by breech birth (born feet first), Down Syndrome babies, or babies who are deformed, is seen as the apparition of a voodoo. In many cases, it is thought that the voodoo may have assumed the appearance of the child. Such phenomena, far from being seen as commonplace, are instead brought into the sphere of the sacred. Children born in this way are called ago and recognised as voodoo.

When an ago child is born, the parents are confined for nine days in the room where the birth took place and the door is closed from the outside. This period of seclusion (called phedhexo) has different purposes: to prepare the parents to come into contact with the voodoo who has been born and ‘initiate them’ into the mysterious powers of the cosmos, separating them from the ‘profane’ world and consecrating them as huno, ‘ministers’ or qualified representatives of the voodoo; and to bring the child into society and to help the parents to accept the voodoo-child. During the phedhexo, the family members spend their time preparing ‘the rite of coming out’, or vidheto, which will allow the child and its parents to leave the house.

After consulting the afa oracle, the paternal uncles go to look for a mother and father who have already had an ago child (and so have become huno or ‘ministers of worship’ of the voodoo ago) and they invite them to come and preside at the ceremony which will take place within a designated period (from three months to three years).

The ‘rite of coming out’ takes place on the ninth day of confinement. The huno mother knocks nine times on the door with her left hand, opens the door and picks up the mat, the loincloths and the money. She then asks for clean loincloths for the child and her parents and gives them to them to put on. She then takes the new-born child outside, touching the bar of the door nine times with the foot of the child. She then takes the foot of the mother, touching the lower part of the door with it and, finally, she repeats the same gesture with the father. The imposition of the name then follows. If the child is a girl she is called Agossì (feminine form of ago). If the child is a boy, the name is chosen from among Agossu (male ago). From now on, the child may not be called by any other name, and cannot become an adept of other voodoo.

Vodulili

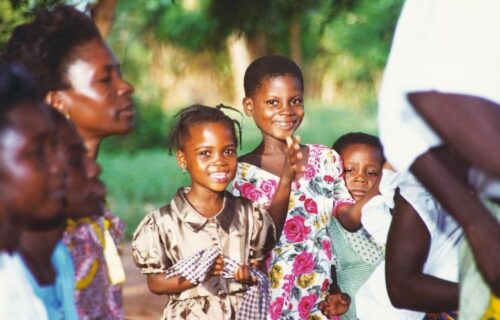

The child may now be taken to the market for the rite of presentation of the parents (asiphephle). Only after this ceremony will the parents be free to go to the market to buy things. The people give gifts in kind or of money to the ago child. When they return, a simple meal is prepared to celebrate this happy event.

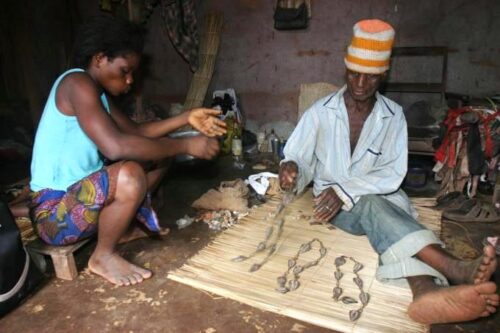

If the parents can afford it, on the day of the vidheto, the vodulili rite, or ‘installation of the voodoo’ also takes place, in the room where the ago child was born. This installation is obligatory since the voodoo now dwells in the house and wants an altar to be erected so as to receive worship and be venerated by the people.

It is from this altar – a privileged place of encounter between the human and the divine – he will be able to show his power and his generosity. In the corner of the room a hole is dug 30-40 centimetres deep into which is placed a jar containing the symbolic objects of the ago voodoo: the head of a viper dwakpata, a rifle bullet, a little gunpowder, small grains of kalikuvi pepper, pieces of bark of the vhuti tree and of the baobab and an object of gold (sikawowo), plus some special herbs (kpanuhehe and adzuca). The hole is then covered with soil and there follows the great prayer (dhephopho) of the ancestors. Afterwards, a chicken is killed and food is prepared for the common meal.

Life force

Once the meal is over, the huno father cuts the hair of the parents and child, for the first time since the birth of the ago child. In this context, the cutting of the hair represents a rite of separation of the ago child and his parents from the ‘profane’ world, to bring them into the sacred sphere of the voodoo. The ‘minister’ then gathers up the hair and will bury it afterwards in the forest, in a place where nobody can find it.

Finding the hair would bring a curse upon the family. Having finished the haircutting, the minister prepares some ‘holy’ water in a vessel in which some special herbs have been placed, and carries out the washing of the parents and the child.

The brief ceremony of the azakplikpli, or ‘reunion of the sleeping-mats’, finally permits the parents to resume normal conjugal relations.

A breech birth is never easy and often, especially in the past, it resulted in the death of the mother or the child, or both. It is understandable that the birth of an ago child is considered an extraordinary event, ‘pregnant with power’. ‘Ago has neither mother nor father’, the prayer says. That is, the voodoo himself comes to live only because he wants to do so, and it is certain that he will be able to overcome, without much help from his parents, the difficulties of life. (A.G.)

Open photo: Village/© Can Stock Photo / homocosmicos