The Unending Saga of Jacob Zuma.

The former president faces two important trials. At the moment, he has only been in prison for three weeks. The strategy is to extend the trial time in order to prevent him from returning to prison because of his advanced age.

In June 2021 Jacob Zuma, President of South Africa from 2009 to 2018, was sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment. His crime was that he ignored an order of the Constitutional Court that he should appear before a judicial commission of enquiry that was investigating corruption and maladministration during the period of his presidency.

In the days immediately following his imprisonment, rioting and looting broke out in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal and in a few other places around the country. Although much of this was opportunistic – poor people seeing the chance to grab some food or consumables – some of it was a genuine, orchestrated political reaction by Zuma’s supporters. Even after all the revelations concerning his corrupt relationships with various business interests, and the collapse of state-owned corporations, as well as social services, that occurred during his administration, he is still popular in parts of the country.

After three weeks, an official released Mr Zuma on ‘medical parole’, apparently because he was unable to look after himself physically. This release was later found to be unlawful by the High Court, but Zuma has appealed against that finding and remains, in effect, a free man.

Palace of Justice in Church Square in Pretoria. ©demerzel21/123RF.COM

This is not the only criminal case that Mr Zuma faces. He is also on trial for numerous charges of corruption which relate to his role in arms purchases and other government deals back in the 1990s, when he was a fairly minor provincial politician.

For many years he and his lawyers have fought endless legal battles to prevent this trial from proceeding; and of course, while he was President, he was able to appoint his allies to the top posts in the prosecution service, and thereby stall the investigation.

For South Africans who value the rule of law, and who understand the importance of preventing public-sector corruption, all this has been extremely frustrating. Hundreds, maybe thousands, of state officials and politicians have followed Zuma’s example, and have involved themselves in corrupt activities costing the state billions of dollars every year. And many of them have also adopted his tactic of launching legal challenges – often on non-existent grounds invented by their lawyers – against every step of the investigatory and prosecutorial processes.

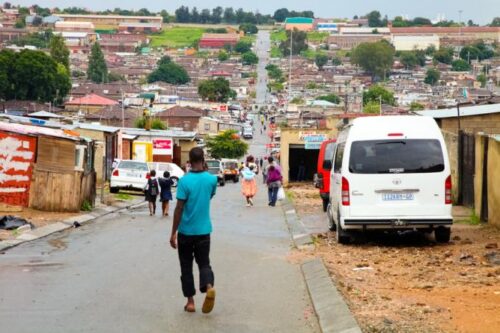

People walking down a main road in Alexandra township, a formal and informal settlement. ©sunshineseeds/123RF.COM

Law-abiding citizens do not understand how Zuma and other corrupt politicians are able to stay out of jail. They increasingly blame the prosecution service, without grasping just how much this arm of the state was intentionally weakened by Zuma when he was President. Citizens are also questioning why the current President, Cyril Ramaphosa, who has committed himself to tackling corruption, does not do more to have people arrested, charged and sent to jail.

All of this diminishes respect for the rule of law, for the courts and for the justice system as a whole. People begin to ask whether there is any benefit in having a constitution that guarantees fair trial rights and due process of law if the result is that figures like Zuma can exploit these rights in order to evade justice for nearly 20 years.

Politically, this saga is an embarrassment for President Ramaphosa. In a constitutional state, he cannot intervene in prosecutions or in the work of the courts; he has to respect their independence. But as long as Zuma and others implicated in large-scale corruption remain unaccountable for their crimes, it will be difficult for Ramaphosa to build a new ethos of clean, honest government in South Africa. In addition, Mr Zuma and his supporters lose no opportunity to undermine Ramaphosa – in their populist rhetoric he is portrayed as a servant of white capitalist interests, while they claim to be on the side of the poor and the marginalised. A cynical reversal of the truth!

123rf.com

It is difficult to know how this will end. Mr Zuma will be 80 years old later this year, and the older he gets the more reluctant the courts will be to send him to jail; it is regarded as inhumane to sentence a person of such an age to the harshness of prison life. Mr Zuma and his lawyers know this and deploy their delaying tactics accordingly.

And even though his age also means that he cannot personally make a political comeback, his followers – including a number of ambitious ministers and senior ANC members – take encouragement from the way he has played the system.

On the positive side, we can at least say that there is still a chance that Zuma will ultimately be convicted. The basic principles of criminal justice and accountability are still in place, but it will require greater determination and a tougher attitude on the part of prosecutors than we have seen so far if they are to succeed in applying these principles to Mr Zuma. (Open Photo: Former president Jacob Zuma in the dock. Photo: Leon Lestrade/African News Agency)

Mike Pothier