The Sahara. In the Shade of the Tent.

The tents of the desert inhabitants are a concentration of technologies, the use of materials and design particularly suited to the environment – which is why they have varied typologies – and to the way of life of those who are always ready to get back on the road

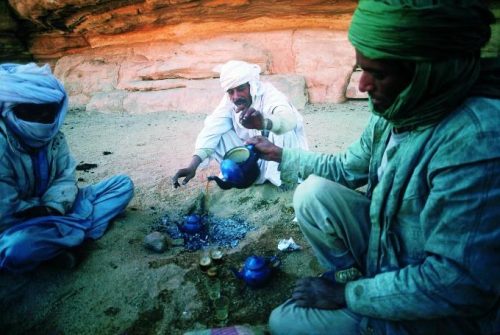

“The first tea is as bitter as life; the second, as sweet as love; the third, as strong as death.” Yislim recites the ancient saying of the nomads of the Sahara while his wife watches over the teapot which bubbles away on a tiny brazier fired with the coals from the previous evening’s fire. All around lies endless emptiness, nothing but sand scorched by the sun and changing dunes shaped by the wind, but inside the small tent, the atmosphere is enveloping and fresh, as if it were a mirage.

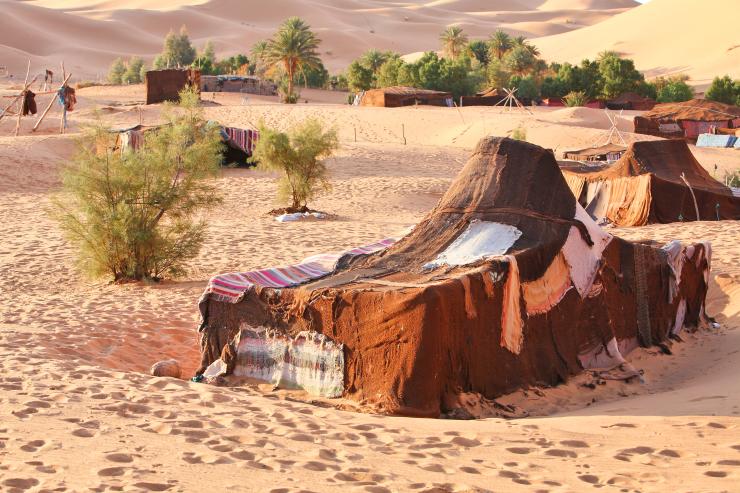

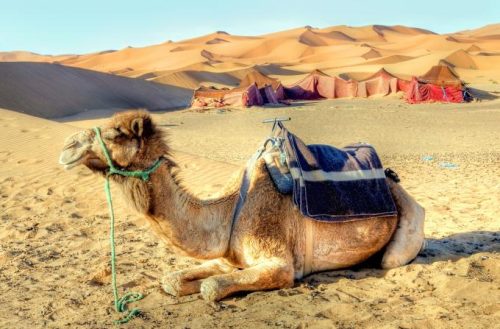

The tents of desert nomads are the absolute pinnacle of architecture. They manage perfectly to combine simplicity, technique, economy of resources, resistance and lightness; it is impossible not to be fascinated by their sinuous and elementary shapes or by the skill with which they are quickly set up, or dismantled and loaded onto dromedaries.

The bedouins tent in the sahara. Shutterstock/Seleznev Oleg

There is no single type of tent: as happens with houses, the different latitudes and climatic conditions, specific local traditions or the availability of some materials rather than others have led to the development of very different models. However, almost all of them seem to recall the surrounding dunes with their shapes, generating that unique dialogue between landscape and architecture that only traditional buildings and technologies can achieve.

The Berber tent is also called the black tent because it was historically made with black goat wool. It is supported by a pair of central wooden poles approximately 2.5 meters high and connected by a crossbar; other larger versions require the insertion of several pairs of timbers of different heights. The anchoring of the cover sheet to the ground is done with a series of sturdy tie rods parallel to the seams in order to

minimize the risk of tears.

The result is a roof with an organic shape capable of offering minimal resistance to the wind, the main risk factor for the stability of structures in these contexts; the spaces between the limits of the covering sheet and the ground are closed with additional lighter sheets or left open during the summer season to allow the air to flow.

Dromedary camel in the desert, nomad tents in the background. Shutterstock/ Chantal de Bruijne

The traditional Mauri khaima manages to further optimize resources: the large square wool or cotton sheet of the covering is perforated at the top so that it can be supported by a single tall central wooden pole, which families have handed down for generations. Other variants widespread among the Tuareg or in the areas between Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia have tents made with mats or skins instead of sheets and with structures made using curved branches that can reach a semi-dome shape.

The desert teaches that everything superfluous is a burden that can even become lethal. Objects therefore often perform more than one function or can be easily reconverted as needed; this is the case of hammocks for children, which serve to stow furniture during the day and as bags for transporting furnishings when travelling.

In front of their house. (File swm)

Among the Moorish nomads, however, the amchaghab, or amsaqqab, is very widespread, a simple table made with finely carved and decorated wooden feet, connected by crosspieces and tie rods on which cushions, blankets and furnishings are placed. While travelling, the same object, turned over, becomes a comfortable sedan chair that allows children and women to travel on the back of a dromedary.

They seem like tales from ancient times, yet even today tens of thousands of people build and inhabit these marvels of ingenuity; new technologies and materials have partially modified some elements without however altering the overall characteristics of the structures.

“The first tea is as bitter as life; the second, as sweet as love; the third, as strong as death.” (File swm)

The sturdy cotton sail sheets, reinforced with double stitching and treated with waterproofing have for years replaced the goat’s wool or the skins of traditional tents, just as steel rods for reinforced concrete have become good and resistant alternatives to perimeter poles or pegs for the guy lines, which in ancient times were made with bushes or tangles of shrubs that were buried in the sand.

Inside, the apparently indistinct space is instead well divided into male and female areas, where the space for the hearth and the loom is usually found. The floors are covered with decorated mats, often even the inside of the sheets is covered with lighter fabrics decorated with geometric patterns and bright colours.

The afternoon sun filters through the coloured fabric and creates a dreamlike atmosphere full of reflections and shades, like the windows of a Gothic cathedral. An essential, austere and ephemeral cathedral, in the heart of the Sahara. (Open Photo: The nomad (Berber) tent in the Sahara, Morocco. Shutterstock/ Vladimir Melnik)

Federico Monica/Africa