The River Niger. A meeting place.

In Mali and Niger, the lives of millions of people depend on the Niger River. Forced to live with the terror of jihadist attacks and military reprisals, and under the threat of an increasingly harsh climate, the inhabitants of the two Sahelian countries entrust their destinies to a river, an inexhaustible source of life, which continues to flow placidly amid the torments of men.

Old Ousmane Djebare Djenepo smiles as he watches the placid waters of the Niger flow around his wooden canoe. The 76-year-old man is one of many Malians who earn their living thanks to the river and the verdant wetlands that surround it. But Djenepo’s smile hides apprehensions. “Before, the river was deep and the fishing seasons were long,” he says. “Now there are far fewer fish and the river has too many problems.” Djenepo heads the association of fishermen in the inner delta of the Niger River, a vast area of land in central Mali. Ecological problems threaten the survival of local populations, already hit hard by the violence of armed jihadist groups that have taken control of the region, governing its most profitable trafficking (drugs, weapons, migrants).

Armed jihadist groups have taken control of the region. 123rf

Since the Islamic militants launched their insurrection in 2012, terror has spread among the inhabitants who live on the Niger, and the repeated attacks on civilians – costing the lives of thousands of defenceless citizens – have emptied entire villages. Due to the insecurity, many farmers have abandoned the patches of land where they once grew courgettes, onions, tomatoes and aubergines. The armed raids by the jihadists, who travel on motorbikes armed with Kalashnikovs, are usually carried out while people are working in the fields, or along the roads on market days when the farmers go to the city with their carts to sell their vegetables. In an increasingly uncertain climate, those who remain can do nothing but entrust their lives to the river, which has always guaranteed daily food and in the event of an attack can represent an escape route. But the problems remain.

The climate change affecting the Sahel, increasingly characterised by prolonged droughts, is draining the Niger dry. File swm

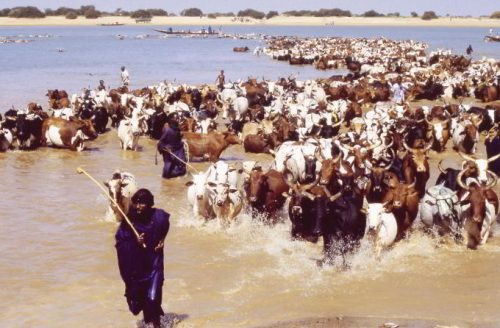

Overfishing has depleted fish stocks in the Niger Inner Delta, and the Sahara Desert is also encroaching on the green floodplains. Concerned Boukary Guindo, director of the government fisheries department for the region, comments: “The situation is going from bad to worse.” The Niger Inner Delta is a complex ecosystem that supports fishing, farming and pastoral communities. During the floods of the rainy season, only pirogues can cross it. But when the waters recede, vast meadows of fresh grass emerge, attracting livestock from across the semi-arid Sahel. Today, this alternation is disappearing.

War among the poor

“The Sahara is ‘swallowing’ the Niger River,” is the blunt view of Hamidou Touré, head of the delta fisheries development office. “Every week, new sandbanks cut off the once productive areas of the delta, and the fish cannot survive in the pools, which evaporate under an increasingly harsh sun.” Also to blame are the dams built since the 1970s, which have altered the course of the third-longest river on the African continent and reduced its flow. Today, the climate of the Sahel, increasingly marked by prolonged droughts, is bleeding the Niger dry.

“The heat causes strong evaporation along the watercourse,” notes Hamidou Touré. “In Bamako, the river has a flow of a thousand cubic meters, but this halves after about 500 kilometres.” And every year, new negative rainfall records are recorded.

High tensions exist between Fulani herders, Bambara farmers, and Bozo fishermen. File swm

“The result is there for all to see: an environmental and human catastrophe waiting to happen,” says Ibrahima Sankaré, of the humanitarian NGO Delta Survie. “What was once the green heart of the Sahel is becoming arid and unproductive. And this is upsetting the fragile balance between populations, which for centuries have ensured peaceful coexistence between Fulani herders, Bambara farmers and Bozo fishermen.” With the progressive impoverishment of resources, tensions are increasing and the rules of customary law devised in ancient times and passed down orally for generations are being undermined. In the dry season, the level of the river goes down allowing small grassy islands to emerge in the middle of the river. The fishermen then move and build makeshift huts and exploit new fishing grounds.

Getting food from the river is a matter of survival, but every human activity in these lands causes environmental repercussions that can cause problems and conflicts.

We civilians are a target

“Our Bozo cousins think fish fall from the sky,” Boukary Guindo says with a sad smile. “They don’t respect closed seasons and raid fish that are breeding, but in doing so they risk decimating the stocks.” Guindo’s work would consist of raising awareness among fishermen about the need to deal with the river responsibly, for example by encouraging them to use nets that spare the smallest fish. However, widespread insecurity in central Mali impedes fieldwork. Since al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadists advanced into this region, the area has become one of the bloodiest battlefields in the Sahel conflict, where the government has little control. “We are at the mercy of bandits and militiamen,” shouts in despair Barthélémy Ouédraogo, a farmer who lives in the red zone – an area considered highly dangerous where the authorities allow access only to the military.

“The problem is that we don’t even feel protected by those who should defend us. The French army and military soldiers who were once stationed in these parts have left the field to Russian mercenaries called to cleanse the area of jihadists. But we civilians are often the ones who end up in the crosshairs of their weapons. We live in terror at the mercy of those who forcefully impose their law.”

Those who pay the highest price for the situation of instability and political uncertainty in the region are the communities. File swm

Security has certainly not improved with the coup d’état of July 26 that removed President Mohamed Bazoum and installed a military junta in power (as already happened in Guinea, Burkina Faso and Mali). For months, al-Qaeda groups have been exploiting the situation of instability and political uncertainty in the region to launch attacks on military bases, villages and gold and uranium mines.

Those who pay the highest price are the communities in the Nigerien area of the so-called “Triple Frontier” (the Liptako-Gourma area) at the intersection of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger: the ones most affected by the jihadist insurgency.

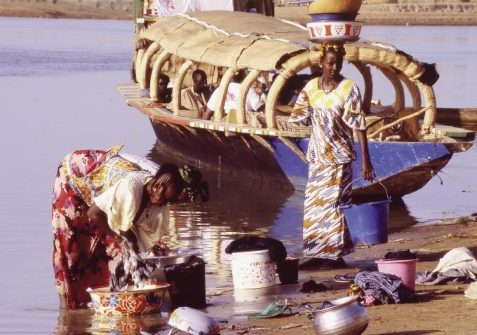

But Niger, despite the environmental alarms and the instability of the regions it passes through, maintains its charm unchanged. You travel at the slow pace of the pinnaces, with their sails made of cement bags sewn together. Enormous patches that intercept the tired breezes of the river, to push people and goods. On the banks, villages made of earth houses and straw domes seem to parade slowly by. The herds of nomadic shepherds are part of the landscape, as are the small pirogues of fishermen looking for a good place to cast their nets. It is that unchanged landscape that inspired Ali Farka Touré, the king of the Sahel blues, a Malian guitarist and singer who died in 2006, whose vibrant music was born on the banks of the Niger and drew strength from its waters. (Open Photo: File swm)

Amaury Hauchard and Pierre Yambuya/Africa