The Paradox of a Country.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, 64 years after its independence, has, for many years, embodied the paradox of abundance. It is very rich in natural resources while its population is extremely poor.

It is the paradox of a country whose lands are home to the Congo basin, the second largest rainforest in the world in terms of size (smaller only that of the Amazon River basin), as well as Lake Tanganyika, the deepest in Africa and the second largest in the continent.The mineral riches of the DRC are among the richest and most diversified in the world and include vast deposits of copper, cobalt (essential for the production of lithium-ion batteries), coltan (essential for the electronics industry), diamonds, gold, tin, iron, zinc, uranium and petroleum.

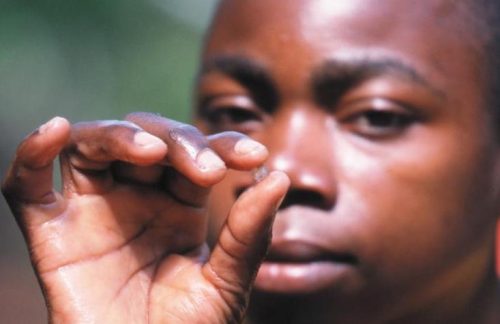

The DRC is the world’s fourth-largest producer of diamonds. File swm

Copper production, for example, stood at 2.2 million tonnes in 2022, making DRC the largest copper producer in Africa, second only to Chile and with the same production as Peru.

The country accounts for about 16% of global diamond production and its oil potential remains largely untapped. It also has enormous agricultural potential: it boasts around 80 million hectares of non-forest arable land, of which only 10% is currently cultivated. If this potential were adequately exploited, the country could move from a net importer to a net exporter of food.

Failed objectives

But the data on the living conditions of the population, combining economic, social and environmental dimensions, are not encouraging. Suffice it to say that it has not achieved any of the Millennium Development Goals, set internationally in 2000 and which were to be achieved by 2015, while significant improvements have been recorded

in other countries.

Today, the sustainable development agenda has set ambitious new goals to be achieved by 2030, but poverty continues to remain pervasive and higher than the average for sub-Saharan Africa.

The DRC is among the five poorest nations in the world. 123rf

The DRC is among the five poorest nations in the world and, in 2022, almost 62% of the population lived on less than $2.15 a day, the threshold adopted by the World Bank to define absolute economic poverty. About one in six people living in absolute poverty in sub-Saharan Africa are in that country.

In 2005 the percentage of people below the absolute poverty threshold was 69.3%, so the situation has improved slightly if read in relative terms. However, in the face of a significant demographic increase, the slight reduction in the percentage has translated into an increase in the absolute number of poor: it has gone from 39.2 million in 2005 (with a population of 56.5 million inhabitants) to 61.4 million in 2022 (with a population of 99 million).

Riches and opportunities wasted

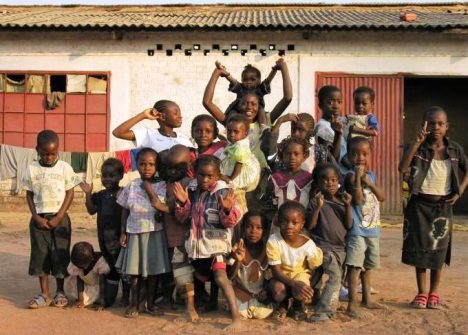

This the story of a country of extraordinary potential riches dotted with missed opportunities, because the high demographic growth (currently 3.23% per year) also means that it is a very young country, with an average age of 15.6 years, that is, with extraordinary energies projected towards the future and an overall population that will double in the space of twenty years.

DR Congo. Group of children. The quality of education is extremely poor. 123rf

Absolute economic poverty is widespread but also very low levels of human development according to the indicators used by the United Nations Development Programme, which uses the Human Development Index (HDI) integrating three fundamental dimensions: health, education and standard of living. Even today, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, life expectancy at birth does not reach 60 years and the infant mortality rate (i.e. the percentage of children who die before they are one year old) is 5%, a very high percentage, which rises to 7.5% considering children who die before reaching the age of 5.

The vicious circle of poverty

The poverty trap is a perverse mechanism that feeds on itself and reinforces itself with poor health, the lack of education, decent working conditions and a living wage – the inability to participate actively in decision-making processes or count for something – and access to resources.However, this is the sort of poverty that does not affect everyone without distinction. Poverty in the DR Congo is not distributed evenly between the regions and the situation worsens where there are conflicts and where employment in the mining sector, especially in artisanal and small-scale mining, has greatly decreased over the years. Then there are particularly vulnerable groups, especially children, people with disabilities, displaced populations, women (especially widows and heads of families), the elderly and indigenous populations.

The DRC is home to a diverse array of indigenous peoples (IPs) who have faced a range of challenges, including forced displacement from their ancestral lands, discrimination, and lack of access to basic services such as healthcare and education. File swm

The poverty trap is a vicious cycle in which poverty itself makes it difficult to escape from poverty because the poor who have limited access to basic rights and resources are more likely to be exposed to violence and conflict. The Indian economist Amartya Sen has repeated it many times: poverty is the deprivation of skills and opportunities that makes people incapable of leading the kind of life they value. And it is this deprivation that takes away spaces of freedom and constitutes the true tragedy of being poor. What is certain is that the future will have to go beyond paying attention to estimates to change things. According to forecasts from the African Development Bank, the economy of the Democratic Republic of Congo should grow – mainly driven by the extractive sector – by 7.2% in 2024. (Open Photo: Mauro Burzio)

Marco Zupi