The Panama Canal.

The Panamanian economy, like domestic and international politics, is strongly linked to the activities of the canal and the services connected to it.

It is no coincidence that, compared to the rest of the region, the agricultural sector is not particularly widespread and that since the 2000s, the period in which the Canal came under total Panamanian control, Panama recorded the highest GDP of the Latin American countries and one of the highest in the world.

This growth was, moreover, increased by the expansion of the infrastructure which allowed a greater flow of containers, making the passage possible not only for Panamax ships, the largest until then capable of passing and transporting 5,000 TEU containers, but also for the Neo-Panamaxes, which carry up to 13,000.

Furthermore, the country constitutes an important logistics hub, as well as a hub for activities related to the advanced tertiary sector and financial services, which represent approximately 70% of the national income and which have also given it the title of a tax haven.

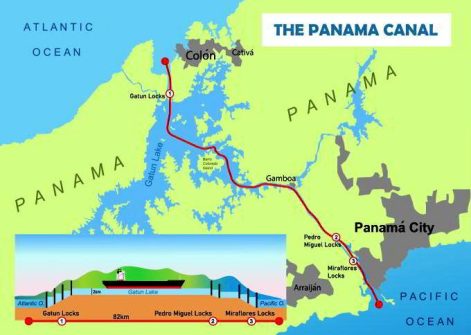

The Panama Canal map. Canal locks. Shutterstock/Zaporizhzhia vector

Over recent periods, drought has drastically reduced revenues from the Canal, causing a slowdown in the passage of ships. The Canal, in fact, with its 81 km of length, is fed by the artificial freshwater lake Gatún, through a complex engineering system of locks to raise or lower the water level, based on the direction of the ship, to overcome the difference in height between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, with the former located in a higher position than the latter.

Thus, the passage of each ship involves a considerable waste of water in a period in which the resource is scarce.

Due to the geostrategic and geoeconomic importance that the infrastructure has, over the last few years it has been a theatre of conflict, fought with investments and threats of sanctions, between the United States and China. The latter, in fact, thanks to its now consolidated presence in Latin America, with a significant part of its imports and exports passing through the Canal, has increased its efforts to expand its influence also on Panama by investing in the infrastructural, technological sector and telecommunications with Huawei and ZTE committed to providing equipment for Panamanian commercial services companies. Beijing’s influence on the Canal dates back, however, to the early 2000s, a period in which the administration of the infrastructure passed – as foreseen by the Torrijos-Carter treaty – from the United States to the Republic of Panama, obtaining the assignment to the Chinese Hutchison-Whampoa company the concessions to manage the ports on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides, thus positioning itself at both ends of the canal.

Transit of the Panama Canal by large sea vessels.123rf

Furthermore, China has also intensified its financial activity through the Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China ICBC, engaged in financing technological projects. In particular, in 2017, under the Varela presidency there was a strong surge in Chinese trade agreements and investments, including the construction of a new port and logistics complex on Margarita Island. The relationship between the two states intensified to the point that, in June 2017, President Varela decided to disavow Taiwan, followed by Xi Jinping’s state visit, which culminated in the achievement of 19 cooperation agreements and Panama’s accession to the Belt and Road Initiative. This situation, obviously, alerted Washington which began to put pressure on the Panamanian government to contain Beijing’s advance which stopped in 2019 with the advent of President Cortizo. The new government, in fact, began to oppose the projects presented by the Chinese counterpart, including the construction of a high-speed train capable of connecting Panama City with the north of the country, worth 4 billion dollars, but also the construction of the Panamanian capital’s subway for a cost of 2.5 billion dollars, the concession of which was delegated to the Korean company Hyundai Engineering, at a cost which was also higher

than that offered by Beijing.

It is located at the entrance to the Bridge of the Americas on the Pacific Side of the Canal. It was built as a reminder of 150 years of Chinese presence in Panama. Shutterstock/Mabelin Santos

Furthermore, the then Panamanian Minister of Public Works Rafael Sabonge also suspended the construction of a bridge over the Canal, originally assigned to a consortium led by China Harbor Engineering (CHEC) and China Communications Construction Company (CCCC). In the opinion of authoritative analysts, Washington’s pressure on the Panamanian ruling class was carried out through the threat of inclusion in the “Clinton List”, which sanctions those individuals who conduct business with people or companies included in the list and which in previous years forced into bankruptcy some Panamanian businessmen including Abdul Waked.

Certainly, in the years to come the Canal will continue to be an object of contention but the United States will hardly allow penetration to other actors in a territory that, historically, they consider their own “backyard”. (Open Photo: A cargo ship entering the Miraflores Locks in the Panama Canal.123rf)

Filippo Romeo