The Gadamoji Celebration.

Every eight years, the feast of final Borana passage called Gadamoji, when a man reaches complete social and ritual maturity, is celebrated.

Due to the fact that it is celebrated at such long intervals and its importance and influence in various aspects of the life of the tribe, this is one of the more typical manifestations of the Borana culture.

When the Bufa moon appears, immediately preceded by the Wachabaji moon, the village of the Gadamoji is completely rebuilt. Each elder builds his own hut next to those who will make the ‘passage’ with him. This results in a wide semi-circle of huts in which the Gadamoji come to set up house with their families.

The doors of all the huts face the single, large cattle enclosure, more or less elliptical in shape and different from that usually used by the Borana to guard their cattle. The usual enclosure has, in fact, just two openings and is in the form of a circle, while this one may be considered a multiple enclosure. Corresponding to the hut of each cattle owner, there are two openings in the hedge: one facing the hut and one towards the other side. The huts of the Gadamoji are different from ordinary huts: instead of one single room, it is formed of a number of communicating rooms. However, there is still only one opening to the outside and anyone wishing to enter or exit has to pass through it. Near the entrance to the hut cattle hides are arranged on which various animals are depicted: lions, buffalos, elephants, sheep or camels. There are also some human figures. They symbolise the wealth and courage of the person being celebrated.

A Time of Peace

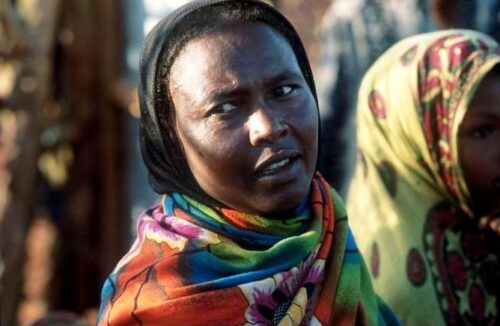

The families of the Gadamoji stay in the village for the whole month, waiting for the celebration. This is a period of peace, tranquillity, and serenity during which, either in the home or in the village, harsh words, unpleasant acts, complaints, cursing and all gestures that may disturb the atmosphere of harmony, are forbidden.

The real celebration commences when the so-called Wachabaji moon appears. On the evening of the New Moon, the men gather in a corner of the hut and, in a circle, spend the night singing to the sound of a drum, chatting and expressing the invocations (ebissa) from time to time. The women gather in groups in front of the dwellings where they sing and dance on hides spread out on the ground.

In the morning, at sunrise, each Gadamoji approaches the opening in the cattle enclosure corresponding to the opening in his hut. There the cutting of hair takes place, a ceremony that is essential to the celebration. Jarsa mata bufadde: the old man whose hair has been cut, is the name given to the man who has completed the passage of the Gadamoji. The haircutting is begun by the wife and finished by the eldest son. The hair is gathered in the palms of the hands and carefully taken by the same son to the prepared place called fodu, close to the entrance to the enclosure opposite that facing the house and is there buried under a heap of cattle dung (on the right side, inside the entrance).

Once the haircutting is finished, the old man enters his hut and stays there segregated for three days. In the meantime, inside the animal enclosure, to the left of the opening facing the hut, each family slaughters a fat calf, called a jarra, and leaves it there with its throat cut.

The procession then follows. All the male children of all the Gadamoji, with their faces painted, their heads crowned with the kalacha (a kind of metal horn tied with a leather strap to their foreheads), each holding in their hands the rod of their birth, called danissa (a black stick pointed like the kalacha), gather outside the enclosure, in front of the external entrance of the first Gadamoji.

A woman with a child on her back and flanked by two girls comes and places herself in front of the place where the hair has been buried. When everyone is present, the woman and the girls start to move, opening the procession which passes through the external opening, through the enclosure and through the internal opening of the enclosure itself, towards the house of the first Gadamoji. The small crowd moves in procession slowly, singing.

When everyone is inside the enclosure, the external opening is closed and guarded by two men armed with whips (lícho) who prevent anyone else from following them. The Gadamoji inside his house finds before him a large vessel full of milk called madala, supported by the usual framework of branches (chanchala).

The procession stops in front of the hut. Only two or three sons are then allowed inside where they call to the old man: buta! He then begins to enumerate, in a loud voice, his former glories, his wealth and his merits. All the other people crowd around the hut to hear what he is saying.

When the old man has finished his speech, those inside the hut come out, carrying the still closed vessel of milk. They open the vessel, dip their sticks in it and apply it to their moustaches saying: afaressa! They then take the vessel back into the hut.

When the procession for the first Gadamoji is over, the children approach the external opening of the enclosure corresponding to the hut of the second Gadamoji and everything is repeated in the same order. The same is done for each ‘passage’ candidate.

Once the processions are over, the fat calf previously left in front of the hut is skinned. Each person has already marked themselves on their foreheads, their throats and also the doors of their houses. Each family group skins its own calf. As always happens when sacrifices are being offered, the skins of the animals are cut into strips, called medicca, which each takes, using a stick and then ties it to their arms. Only the wife of the Gadamoji, who, on this occasion, wears the traditional hide (gorfo) and carries a sort of rattle made of small gourds tied together (usually called saka but in the case of the wives of the Gadamoji, called a hapa) places the medicca around her neck.

The meat is taken into the huts and cooked. There is plenty for everyone. The next night is also spent dancing and singing. After three days, the elders come out of the huts and that concludes the celebration which will be repeated every eight years when hair will be cut at the following Gadaa. Gadaa, like lubba, means age-group or class.

Uncertain future

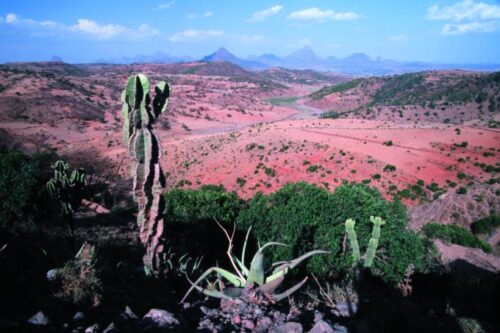

Today the territory of the Borana is regularly struck by periods of drought. The elders recall the time when ‘the sky was friendly’ and the regular rain allowed people to live happily according to the movements and settling of the nomadic life. There is a real danger that the ongoing rapid process of desertification may force the group to abandon for good the savannah where, for many generations they have pastured their camels, oxen, cows and herds.

The rains are less frequent and the problem of water supplies is becoming difficult. There is an increase in arguments, conflicts and even armed clashes (with lives being lost), that are often caused by attempts to use, even illegally, the few wells still functioning.

It seems certain – and the representatives of the nomadic groups said so during their various meetings organised in Kenya, Tanzania and Ethiopia – that the nomadic life has a poor future in eastern Africa and in the Horn of Africa. Boundary conflicts, population growth and progressive desertification are leading to water sources drying up.

While it is true that human mobility and the pastoral life still strongly permeate Borana culture and tradition, nevertheless, the difficulties and disadvantages of nomadism today exceed the benefits of the past. Sickness, drought, malnutrition, environmental degrading and the high cost of moving are forcing communities to become sedentary.

There is an urgent need to introduce appropriate methods of using the agricultural land, without excluding a degree of mobility of herds, which must not cause any further deterioration of the environment. Commercial exchanges may be promoted to create work and increase sources of income. Above all, what is needed is new infrastructure: roads, schools, health facilities and access to potable water. There is no other way to guarantee the survival of the Borana in the territory they have lived in for centuries and to preserve their cultural aspects which forged their identity and their structures of social relationships.

Provvido Crozzoletto