The Cities of Africa. Urban and Decolonial.

The key to understanding the growth of cities in the African continent.

At a frenetic pace, Africa has gone from being the least urbanized continent to be the fastest urbanizing region on the planet. With urbanisms and complex dynamics as diverse as the histories that have shaped them, African metropolises today stretch across the continent like authentic dystopias. Capitals like Bamako (Mali), port cities like Lomé (Togo), secondary cities like Saint Louis (Senegal) or smart cities like Kigali (Rwanda) are authentic social hotbeds and spaces where cultures and different ways of being in the world meet. They are an inevitable continuum that provides different answers to common challenges.

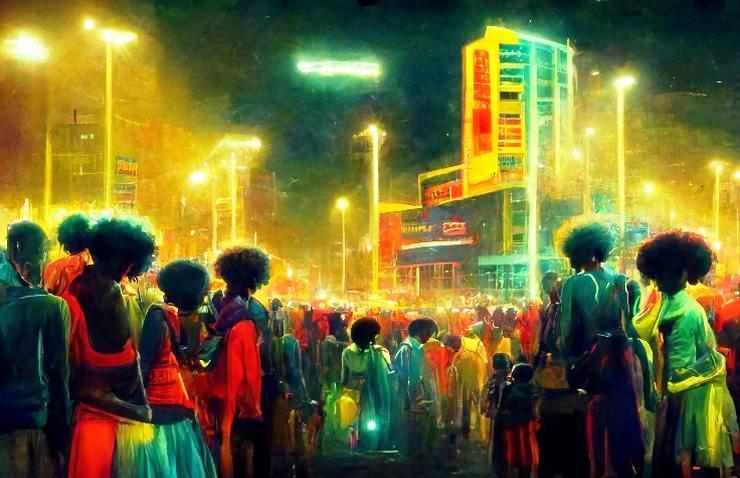

Kampala. A crowd of people on the streets and heavy traffic. 123rf.com

Although the main approaches that are being made to urban Africa are aimed mostly at focusing on challenges, one of those that relate most to the media is its dizzying population growth.

The population growth that African cities are experiencing is not comparable to anywhere else on the planet. Furthermore, the peculiarities of the rapid transformation of urban spaces in the southern Sahara make them perfect paradigms of what the urban theorist Mike Davis had already baptized in 2005 the ‘planet of slums’.

The phenomenon of African urbanization is challenging to say the least. It is wrong to think that the African continent was rural before colonization. As the historians and chroniclers of the time testify, while Europe remained closed in on itself during the Middle Ages when most of the population was afflicted with diseases, African urban residents were more numerous.

However, modern urban history reveals vertiginous transformations. While in the 1960s the population of cities did not reach 15%, by 2030 half of Africa will already be urban and by 2050 its streets will host more than 60% of its population.

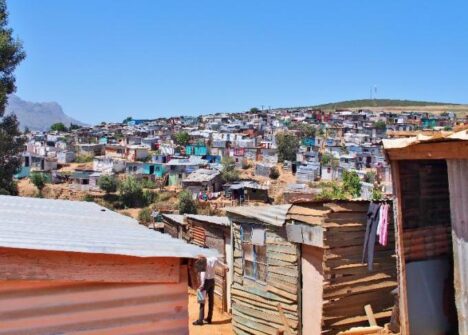

Angola. Luanda City. 123rf.com

Very soon, in fact, Africa will host six of the largest megacities on the planet. While Lagos (Nigeria), Cairo (Egypt) and Kinshasa (DRC) are about to host more than 20 million inhabitants, Luanda (Angola), Dar es-Salam and Johannesburg (South Africa) will exceed 10 million inhabitants.

The most recent demographic studies identify three fundamental causes of this ‘urban revolution’.

The main one: the natural growth of the population due to the increase in life expectancy and the birth rate. Secondly, there is the rural exodus because, although in the decade of independence there was an important element of attraction, this has ceased to be a relevant component beyond particular cases such as that of refugees. And, to a lesser extent, the reclassification of the urban territory and the birth of secondary cities, the most numerous on the continent.

Informal settlement on the outskirts of Stellenbosch, Western Cape province, South Africa. 123rf.com

Overwhelmed by the unstoppable trend towards urbanization, the anguish of urban planners and local administrations is palpable, aware of the serious implications of urban laissez-faire in the international agendas of the last century. What consequences does such a hasty and profound transformation entail for African societies? Who is responsible for the continent’s current urban unsustainability? How does the use of second-hand vehicles from Europe pollute the air the Dakarois breathe and how to reverse it? How did the supply crisis affect the restriction of international flights in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic? What about the current Russia-Ukraine war?There are countless worrying aspects that we could explore when we talk about contemporary African cities. But in each of them there is a structural response that refers us to colonization and post-independence.

Who is responsible?

It is not only the way ancient metropolises designed modern African urbanism that must be held responsible for today’s urban dysfunctions, but also the urban response to the multipolar world in which we live. It is no coincidence that Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), the headquarters of the African Union, is the city that has invested the most, with the support of China, in public transport or road infrastructure, having been the first to build a subway in the 2015, or that it has a promising textile and clothing industry that is making it known as ‘the new Bangladesh’.

The protests that triggered the usurpation of Oromo lands in 2014 for the expansion of the Ethiopian capital, and that form the backdrop to the current war that the federal government supports in Tigray, have no place in the state’s accounts. The fact is that, like Addis Ababa, African cities generate 50% of the gross domestic product of the entire region, becoming real centres of economic power. The question of who (and how) controls this power is probably the crux of the matter.

One of the most evident characteristics of the African urbanization phenomenon is poverty. Globally, and with great nuances, depending on the country, about 62% of city dwellers live in informal settlements. This means that most of Africa’s population growth occurs in poor neighbourhoods and where the majority of the population depends on the shadow economy. In this sense, the African urbanization process has nothing to do with the Western one. While other continents such as Europe have seen the growth of urban areas due to the rural exodus of an industrial proletariat called to provide labour in factories installed in urban centres, Africa is experiencing a process of urbanization without job opportunities that have no similarity even to the other continents in the southern hemisphere. Unsurprisingly, a stereotypical image of African cities is being built as degrading, indecent and hopeless spaces. But exclusion and marginalization also have their genesis.

In Africa, modern urban projects were designed as part of the extractive goals of colonial administrations. Colonial cities projected urbanisms that only served their purposes. It can be seen how cities that fell under the Gallic yoke such as Abidjan (Ivory Coast) imposed urban planning that reflected their model of direct control, and where it was intended to be able to control as many meters as possible from each road intersection. Meanwhile, cities developed on the British model such as Nairobi (Kenya) are the reflection of an indirect rule very much

along the lines of apartheid.

The municipal urban plan of Nairobi dates back to 1948.

The capital of Kenya, to name a specific case, was a ‘tricolour city’ where white British officials lived in the highest places, avoiding malaria. Blacks, at the other extreme, were barred from entering administrative and commercial areas. There were building permits that Blacks couldn’t afford, as well as imported building materials that they couldn’t access. Meanwhile, the Indian community, who arrived as a kind of second-class citizen in the service of the colonial administration, stood between the two and was given permission to build near the white residential areas. An exclusive urban plan was thus imposed, safeguarding the minority of settlers from the municipal regulations that made the presence of the local population illegal.

A direct consequence of this is that today, and in conditions of overcrowding and administrative neglect, 5% of the Nairobi area is inhabited by 60% of its residents, while a minority owns most of the city with garden houses and barbed wire trying to protect the privilege of having inherited power and right. This is what is known as the colonial slab of African urbanism.

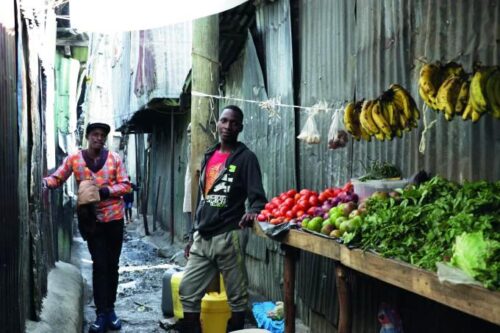

Kibera is the largest slum in Nairobi and the largest urban slum in Africa.

Post-colonization continues to affect the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those first rural migrants who arrived in the new Nairobi, the city that was built on the land of the Maasai practically from scratch to build the railway that connected Uganda with the port of Mombasa (Kenya). A panoramic look at the famous slums of Kibera, Mathare or Kawangware, shows an agglomeration around the swampy areas where improvised toilets emerge during the rainy season, simple plastic bags with faeces flung from windows forming waste sediments in the absence of toilets and water pipes. After all, why would a government invest in informal settlements that keep speculating and selling poor land to wealthy landlords who ceaselessly build condos and shopping malls? The municipal urban plan of Nairobi dates back to 1948. It is enough to consult the local press of any city to see how the scourge of forced evictions in poor neighbourhoods manifests itself daily in all cities of the continent.

The cities of the continent are today an amalgam of centrifugal forces in decolonization where municipal laws do not yet reflect their real actors or their needs. Urbanization and decolonization are an inseparable couple in contemporary Africa, and each city will decide, with a greater or lesser degree of violence and conflict, how to lay the foundations for the future, already undeniably urban for all. (Illustration: 123rf.com.)

Gemma Solés i Coll