The Church Raises the Voice.

Since independence, the Church has been somewhat close to the MPLA, although it has always opposed civil war and worked for reconciliation.

A turning point in relations between the Church and the MPLA took place in 2015 when protesters who supported the activists of the Angolan Political Prisoner Support Group tried to gather on the square and inside some churches of Luanda (Sagrada Família, São Domingos and the churches of the Upper Town).

The Church was divided, but in the end decided to support the activists, while the security forces decided to intervene, entering the places of worship. This gesture marked a division in the relationship between the Church and the government.

Over the years, the Catholic Church has intervened in the main problems that affect the lives of Angolans. It had its say on poverty, hunger, inequality, natural resources and environmental protection, violence and lack of freedom. In this sense, it has played and continues to play a prominent role both nationally and continentally.

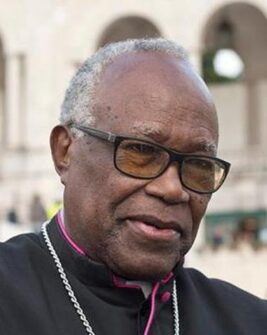

Archbishop emeritus of Lubango, Zacarias Kamwenho,

Relations with the MPLA are well exemplified by the interventions of the archbishop emeritus of Luanda, Bishop Zacarias Kamwenho (Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought in 2001) and the bishop of Cabinda, Bishop Chissengueti, current spokesman of the Episcopal Conference of Angola and of São Tomé and Príncipe (CEAST).

Last December, Bishop Dom Zacaria Kamwenho criticized President João Lourenço, arguing that he is making Angola ‘his private constituency’ and that ‘Angola is tired of being a constituency deprived of its party’. And he did not limit himself to this. He asked for changes: an end to illusions related to the fight against corruption, a profound transformation of the MPLA, a solution to the discontent that is stealthily entering the population and respect for the Constitution. It is possible to look at this intervention as representative of the Church’s position and a response to the hostility, on the part of some members of the MPLA, towards bishops who raise their voices and demand the rule of law.

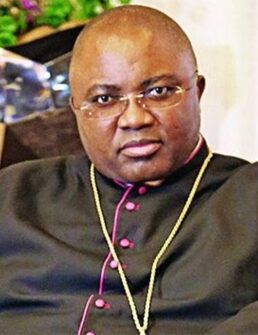

The Bishop of Cabinda, Belmiro Chissengueti

As for the new bishop of the exclave of Cabinda (a territory of northern Angola that borders the Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo and separates it to the south from the rest of Angola with a narrow strip of land), Bishop Chissengueti pacified the Catholic community of the exclave, known for its opposition to the central power. While, on the one hand, the Bishop of Cabinda constitutes a factor of unity in the Church and of closeness to the rest of Angolan society, on the other, he does not limit himself to dialogue, but also raises issues. Aware of the social problems (poverty, hunger, and youth unemployment) of a territory that is the largest oil producer in the country, Bishop Chissengueti argued that ‘the Church must not be afraid to get her hands dirty to defend her brothers and sisters’ and must make her voice heard not only to spread the Gospel but also to denounce social problems. On the regional question, Bishop Chissengueti raised two questions: Cabinda continues to have a poor population with few educational and health care opportunities, while the territory produces crude oil that amounts to 80% of the GDP.

There is poverty in the villages while investments are concentrated in the cities where the institutions are located; this causes internal migration to urban centres and the consequent desertification of rural areas. Meanwhile, the Episcopal Conference of Angola and Sao Tome (CEAST) has expressed itself several times on issues that have to do with the ‘state of health’ of the country, such as freedom, the right to vote, the rule of law, democracy, the good functioning of the institutions (also with reference to the recent decision of the Constitutional Tribunal to annul the internal election of the president of Unita, a historic opposition party) and on balanced regional development. The Church’s vision is based on human development, communities, and essential goods, very different from the extractivist model that exploits oil reserves without the slightest concern for generalized poverty and future challenges. The Church echoes the discontent coming from all the provinces, especially from young people: its position is increasingly aligned with the sentiments of civil society.

Last February, in a statement on the occasion of the first Plenary Assembly of the Conference, in view of the general elections, the bishops stressed that ‘a strengthened democracy, by its nature, undoubtedly contributes to the affirmation of human dignity, to the strengthening of justice, peace and the well-being of citizens’.

For this reason, they invite ‘Catholics to avoid abstention’ and ‘to renew their electoral cards’. ‘The elections will take place according to our hopes if they are well prepared in truth, transparency, honesty and justice’. For this reason, the CEAST hopes for the promotion of ‘civic education of citizens’ so that ‘education for democracy is cultivated’.

The episcopate also invites the political parties to observe mutual respect during the electoral campaign, because the vote will be truly free only if the electoral campaign ‘is based on mutual respect and if all recognized subjects have the right and the possibility to express their opinions’. (Photo: The Catholic cathedral in Luanda. CC BY-SA 3.0/Fabio Vanin)

Marc Jacquinet and Ufulo Mbanza