Suriname. A Multi-coloured Country.

It is the smallest country in South America with a population of just over 600,000 inhabitants and a population rate that has been steadily decreasing since 1970. About 245,000 people live in Paramaribo, the capital. Located near the mouth of the 480 km long Suriname River that crosses the country from south to east, colonial architecture predominates in the city and the historic centre is

a UNESCO heritage site.

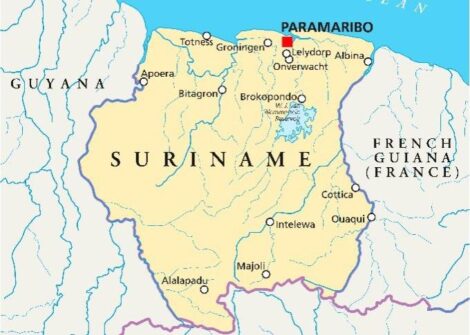

The country is located on the Atlantic Coast, even if it is considered a Caribbean country, and is nestled between French Guiana, with which it borders to the east, Brazil to the south, and Guayana to the west. The country occupies an area of 163,821 sq. km of which about 80% is covered by uncontaminated rainforest. It is rich in waterways and mineral resources and is in continuity with Guyana both geographically and morphologically. In the past, these territories, which constituted a single segment, were perceived by the Spanish and Portuguese as unhealthy and not to be dealt with, despite being located in the part of the South American continent closest, as the crow flies, to Europe or, more precisely, to the Iberian Peninsula.

Suriname political map with capital Paramaribo. 123rf.com

This refusal was perhaps determined by the presence of swamps and the appearance of the forests. Unlike the Spaniards and the Portuguese, the English, the French and, above all, the Dutch – the latter belonging to the powerful West India Company – did not disdain to establish themselves in those territories on which they established their respective sovereignties, carrying out a division into three parts defined as follows: British Guiana, Dutch Guiana or Suriname and French Guiana.

The name Guyana probably derives from the name of a village called ‘Guyane’ already present in those territories and inhabited by indigenous people. By founding the first establishments with exclusively commercial purposes, the settlers effectively began colonization through the abundant use of slaves imported from Africa. In the course of the following centuries, Dutch Guyana or Suriname changed hands several times between the English and the Dutch depending on which country held the balance of power. The reclaimed territories were used for coffee, cocoa, and sugar cane crops. However, the settlers had to face the problem of manpower since Indians, Black Africans, and Creoles did not want to work in the plantations under their orders and, therefore, decided to withdraw to the virgin forests, little known at that time.

This forced the Dutch to enter into five-year contracts with the mostly Chinese and Indian workers employed on these plantations.

In the following years, in addition to these crops, stock-raising, the mining of gold and bauxite, as well as the production of timber

were also developed.

Cannon at fort Nieuw Amsterdam in Paramaribo. 123rf.com

In the history of Suriname, 1950 undoubtedly represents an important date since in that year it was granted self-government by the Netherlands. This process, which became complete in 1954, allowed Suriname to become part of the kingdom of the Netherlands and therefore to develop its own political life characterized by a close confrontation between the National Party of Suriname (PNS), an expression of the black and mulatto majority who favoured independence, and the Asian-backed Progressive Reform Party (PPR), which advocated maintaining ties with the Netherlands. This confrontation reached a turning point on 25 November 1975 with the achievement of independence by the country which, however, throughout its history was not immune from interference by the military who, as in many other countries in the region, played a crucial role in the political equilibrium of Suriname by determining its isolation from the rest of the international community.

In 1975 a new government was formed headed by the major representative of the National Party Henck A. Arron and whose members were representatives of various ethnic groups – Creoles, Africans, Indonesians and Chinese – while many Dutch citizens returned to their homeland and Holland allocated a few billion florins to help Suriname take its first steps with a certain degree of tranquillity. However, after about five years of activity, Arron’s government was overthrown in 1980 by a military coup and replaced by the military junta, chaired by D. Bouterse who imposed two years of martial law on the country, after which, following harsh protests by the population, a constituent assembly was appointed which produced a constitutional text approved in 1987. During those five years, the country was isolated, which caused both a decrease in exports of aluminium and bauxite and the suspension of economic aid from the Netherlands and the United States; factors that aggravated the country’s already precarious economic situation.

Ferries in port of Paramaribo. ©mathess/123RF.COM

With the launch of the new constitutional charter, new elections were also held which ended with the victory of the Front for Democracy and the affirmation of Ramsewak Shankar. However, Bouterse was appointed head of the Military Council, and this allowed him to have control of domestic politics. This balance showed all its precariousness after just a short time, dissolving in 1989 when the government tried to reach peace with the ‘bosch neger’ (descendants of slaves who fled to the forests) who had already been defending their autonomy since 1986. They met with strong opposition from the military who sent against them the ‘Amerindians’ of the Amazonian Tucayana. In the face of this pacification process implemented by the government on December 24, 1990, the military overthrew R. Shankar and called new elections, held on May 25, 1991, which assigned the victory to the nationalist New Front and the presidency to R. Venetiaan.

The National Assembly in Paramaribo.

The new government concluded an economic assistance agreement with the Netherlands, promoted constitutional changes to limit the influence of the military, and formalized Suriname’s entry into the Caribbean community in 1995. The constitutional changes did not prevent Bouterse from playing a crucial role in the political life of the country in the years that followed. After several ups and downs, which also saw him involved in drug trafficking, he finally returned to the vertex of the state in 2010, when he was elected president of the Republic, confirming his mandate also in 2015. The last presidential election was won by Chandrikapersad ‘Chan’ Santokhi, a former police officer and exponent of the Vooruitstrevende Hervormings Partij (Progressive Reform Party, VHP), a social-democratic party founded in 1949 by the union of old Hindu and Muslim parties. (Open Photo: 123rf.com) (F.R.)