Sudan. Art against war.

Marked by decades of political instability and conflict, Sudanese artists narrate the complex reality of their country through works that reflect their identity, originality and resilience.

Riahiem Shadad is an art curator. He owned an art gallery in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, called Downtown Gallery, where nine artists from his country were represented. However, the civil war that began in 2023 destroyed the gallery. Providentially, Rahiem had started preparing a travelling exhibition a year earlier, with the intention of taking it to several European countries. “I wanted this exhibition to show Sudanese art and give it a face… This was the idea before the war, luckily because we sent the works on Thursday, April 12, 2023, and the war started the following Saturday. It was a coincidence that we left in the last hours when the airport was working because it was the first target to be attacked,” Shadad tells us.

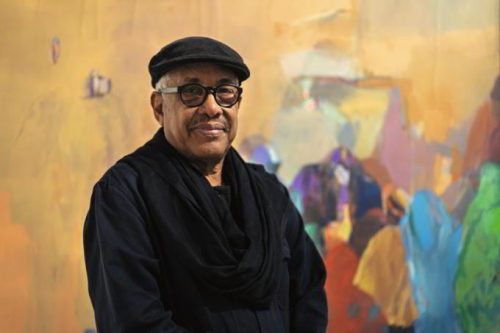

Riahiem Shadad is an art curator. He owned an art gallery in Khartoum. Photo: Laura M. Lombardía

And suddenly the exhibition that Shadad had titled “Troubles on the Nile” took on a whole new meaning. “We had not planned to defend the Sudanese people and tell their story, but suddenly we felt responsible. It was our duty,” the Sudanese curator explained. Rahiem Shadad explains that the name “Troubles on the Nile” “is not about the war, but about the turmoil that Sudan has experienced over the past thirty years and how it has affected art.”

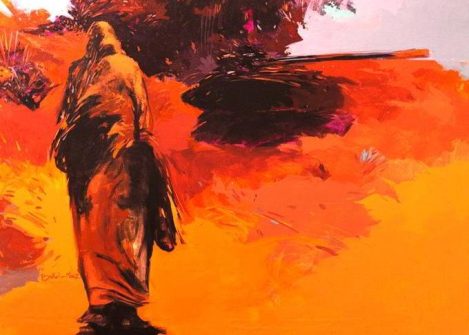

“The exhibition spans several generations of artists and each of the works has experienced its own war. With the current war, we have added two videos and there is an additional painting, by Bakri Moaz, done later, of a woman walking next to a tank. At the moment, the paintings by Waleed Mohammed on display are the only three that remain from his studio. The same goes for Rashid Diab. That the collection in his house in Sudan was lost is absurd. I have been there several times and there were hundreds of paintings and works. God only knows what happened to them”, Rahiem said.

Art is a relationship with influence

Of the nine artists represented by Downtown Gallery and with works in the travelling exhibition “Troubles on the Nile,” three have lived outside of Sudan and have been influenced by the diaspora. Rahiem Shadad continues, “I think anyone who sees the paintings will immediately see who has lived outside of Sudan and who has always stayed in Sudan.”

Works by Sudanese artists on display in Madrid. Photo: Gonzalo Gómez

“Rashid Diab, Eltayeb Dawelbait, and Miska Mohmmed have all lived abroad. Sudanese artists are, for the most part, quite classical. If they use oil, they paint everything in oil. They don’t do a lot of collage or mixing. It’s something to do with school in Sudan and art education. However, with the three artists I mentioned, you can immediately see that they break the rules. Dawelbait paints on wood and then scrapes it off. This is an unusual practice, especially for artists his age. Rashid uses monochrome to create colour transitions and then paints over them, accentuating the impression of depth and movement. Miska paints landscapes. His subjects are classical, but he draws with horizontal lines and uses green and blue colours that are not the usual yellows and browns, more common in nature in Sudan. He learned this in Kenya from the artists who attend the Makerere School in Uganda”.

The Sudanese artist reflects experience

The older artists of the group of nine works in this travelling exhibition—which has been shown in Paris, Madrid, and Lisbon—represent a generation that lived through the Arabization of the regime of al-Bashir, president of Sudan from 1993 to 2019. At the time, everyone had to obey a model that greatly limited expression and individuality. “If you look at the artists of that period, they deal with themes related to the community as a whole, they rarely talk about themselves. Mohammed A. Otaybi, for example, paints African faces as masks with Arabic calligraphy. It is a statement against the government, a denunciation of what it was trying to do by forcing Sudanese people to be Arabs and Muslims. His paintings say that there is an African identity mixed with an Arab one. We accept both identities and embrace them…”,

explains Rahiem Shadad.

A woman walks towards a tank by artist Bakri Moaz. Photo: Gonzalo Gómez

The art curator goes on to explain the differences they perceive in the group: “But if you look at Yasmeen Abdullah, she paints what she feels, it’s not about what her community is experiencing. Reem Aljeally also paints her bedroom, she reflects on the limits of women, their participation in society and the invasion of women’s privacy in modern Sudan. Her work is located between the public and the private and is very personal.” In this context, Rahiem highlights “Waleed Mohammed, whose origin is an African tribe from Darfur, but whose family moved to the Arab state of Al-Jazeera, dominated by Sudan since 1930. In his paintings, there is a personal search, but relevant to many individuals who are going through the same identity issues.”

The impact expected from the exhibition

Rahiem Shadad hopes the exhibition will help people understand what Sudan is and see it differently, humanising its history and the numbers, such as the twenty million deaths the war has already caused, while also identifying those who are struggling to survive. He says: “The World Food Programme says there are 18.6 million people in Sudan at risk of famine. Our fellow artist Waleed Mohammed is one of them. This is a humanising story. We cannot communicate with him. I am sure he has lost half his weight because there is no food. There is nothing in Khartoum. The 18.6 million Sudanese with food shortages is nine times the population of Gaza. So, I hope that if something can be done, it will be done. In addition to the exhibition, we provide information and there is a lot of documentation on the Internet about how to help.” Art lives in exile and Rahiem Shadad regrets that the travelling exhibition is living in exile: “These works of art should return to Sudan, but they can’t because of the war. The nine artists are scattered across six countries.”

Rashid Diab, artist and researcher. Photo: Gonzalo Gómez

Rashid Diab is one of them. He lives in Spain. An affable character, he says he is sad. The war in his country made him lose everything: work, home, the gallery… According to the news, everything has been destroyed.” Rashid had already lived in Spain in the 1980s and 1990s. He earned a doctorate in Fine Arts on the philosophy of Sudanese art and returned to his country in 1999 because, in his opinion, “If we all leave and don’t come back, we are not helping our people.” Upon his return, he opened an art gallery and founded a cultural centre … which was destroyed by the war in 2023. He explains that, for him, “The root of wars is the lack of understanding between peoples and the best way to understand each other is through the appreciation of art. We must realize that the artist does not paint a picture for his own people but for all of humanity”. (Open Photo: A group of Sudanese women talk and walk in this work by Rashid Diab. Photo: Gonzalo Gómez)

Gonzalo Gómez