Seeking to control the Northeast.

The thirty-year instability of the mining provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu and Ituri is an indicator of the voracity of neighbouring countries, the obtuseness of the Kinshasa government and the lack of interest on the part of the international community. A state of war that also has ethnic implications.

Compared to 2018, the elections last December 2023 had an additional and rather cumbersome obstacle: the armed group March 23 (M23), a survivor of the enormous combined civil and foreign war that took place in the Democratic Republic of Congo between 1996 and 2007. M23 was a remnant formed in March 2012 as an armed extension of the Congolese Rally for Democracy which had lost heavily in the first post-war elections. Having disappeared from the Congolese political scene after an attempted insurrection, the M23 brutally reappeared in the northeast in November 2021 as an unofficial but heavily armed embodiment of Rwandan interests.

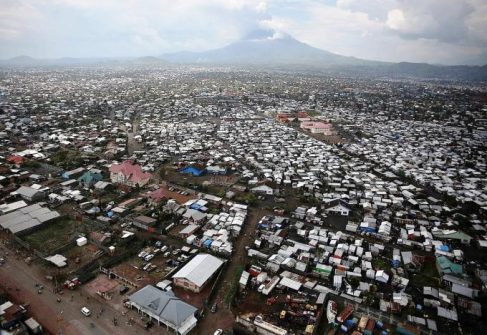

The city of Goma, North Kivu. Clashes with the M23 rebels have moved closer to Goma in recent weeks, causing the U.N. peacekeeping mission MONUSCO and the Congolese army to launch a new operation to reinforce its security perimeter.

Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0/Abel Kavanagh

This added an explosive international touch to a state of war inherited from the conflict at the beginning of the century which had left behind a disjointed society, whose positive symbol was and is Dr. Denis Mukwege, 2018 Nobel Peace Prize winner and a candidate for the presidency in past elections.

An ethnic headache

Specific studies have estimated that there are 120 armed groups in the northeast: if the M23 is but one of these, its political cohesion, discipline and modern weapons make it a leading player. Its political positioning derives from the horror of the Rwandan genocide (1994), even if it had nothing to do with this tragedy (the ethnic basis of the movement is Tutsi, but it is an extension of the Rwandan population not a Congolese factor), but proved useful to the iconic figure of Rwandan President Kagame. Many of the armed groups are ethnically based formations and some such as Codeco (Cooperative for the Development of Congo, Lendu ethnic group) and M23 itself (Banyarwanda Tutsi) are ethnically limited. Others approach forms of banditry. There are also actors with complex links to foreign countries through entirely different connections.

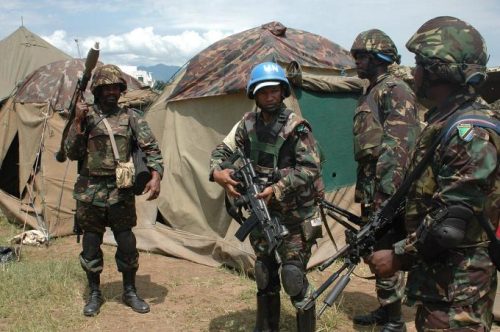

Tanzanian soldiers of the UN brigade deployed in the city of Kiwanja, 75 km north of Goma, Rutshuru territory. CC BY-SA 2.0/ ONUSCO/Sy Koumbo Singa Gali

For example, the members of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Rwanda (Fdlr) – heirs of the Rwandan genocidal Hutu groups who sought refuge in Ituri where they took root – have become a Congolese ethnic group which serves as an “anti-genocidal” pretext for President Kagame to justify the existence of M23 (which he denies supporting) which opposes the Fdlr.

There is also a regional military force which is the expression of the East African Community. As well as an Islamist terrorist group, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), coming from Uganda and linked to the Islamic State group. The ADF operates in DR Congo because the weakness and military incapacity of the Congolese army facilitate the holding of a base. To continue their cross-border war, Ugandan troops have followed the ADF and are now fighting alongside the Congolese army.

Kagame forges ahead

Faced with general confusion, Congolese civil society, which serves as a battleground for all the different forces, is reacting with increasing frustration unfortunately, justified by the brutal behaviour of all the actors. Local defence groups, exasperated, protest to the Kinshasa government against the presence on the ground of their enemies’ enemies. This state of affairs had led President Tshisekedi to proclaim on 25 September a “new war” against the M23 which focuses much of the popular resentment on itself.

The provinces that have been under a state of siege for two and a half years – civil institutions are suspended in Ituri and North Kivu – have become open ground for resolving all regional disputes.

The Burundian army troops themselves, who entered South Kivu with an explicit mandate from the African Union, found themselves the target of attacks without knowing by whom they were being attacked. CC BY 2.0/sedaf

To the point that the Burundian army troops themselves, who entered South Kivu with an explicit mandate from the African Union, found themselves the target of attacks without knowing by whom they were being attacked. Paul Kagame seems to continue to think that his aura of “Liberator from Genocide” – which dates back to 1994 but, due to his questionable subsequent actions, doubts are being raised as to its validity – gives him a sort of global blank check that allows him to deny the evidence. The United Nations has published two reports, in June 2022 and June 2023, reiterating allegations of Rwandan support for the M23. Not only does Kagame continue to deny it, but last August he also promoted and decorated General André Nyamvumba, whom the Americans themselves – who have long been Kigali’s biggest supporters – had condemned for his actions in the DR Congo.

International duplicity

The international community has proven to be incapable of forming a common front in the face of the catastrophic situation in the north-east of the Democratic Republic of Congo where there are no fewer than five million displaced people. The most hypocritical were the French who, to “redeem” the shame of having for so long supported the Rwandan regime responsible for the genocide, tried to effectively deny the accusations of interference made against the Kigali regime to which they paid (last March) 34 million euros in special aid. Given the collapse of the French presence in Africa, marked by a succession of coups d’état from Mali (2020) to Gabon (2023), having a renewed superficial friendship with Kagame has become a kind of partial insurance policy for Paris to try to prevent the Russian presence from replacing that of the French.

Rwanda flag on soldiers’ arm. 123rf

Last December, Great Britain signed a new agreement with the Rwandan regime to send to Rwanda all those who, African or not, do not have the right to political asylum recognized in England. The Americans, on the other hand, are hesitant. The kidnapping in the Middle East and the summary trial of Paul Rusesabagina (the film Hotel Rwanda tells how he saved many lives during the 1994 genocide), later sentenced to 25 years in prison for supporting the Rwandan opposition, marked a distancing from the Kagame regime. The release of Rusesabagina last March softened the US position but did not lead to any condemnation of the presence of the M23 group in DR Congo. Exasperated by the passivity of the UN Mission (MONUSCO, present in the north-east for 23 years), the Kinshasa government has asked for the withdrawal of the international mission which, although not very operational, represents a symbolic eye open to the north-east.

The city of Bukavu, South Kivu. CC BY-SA 40/Abel Kavanagh

This is better than nothing, given “incidents” like the one on August 30th which led to a massacre (48 dead and 56 injured) during a ceremony of the Wazalendo sect in Goma. The M23 accuses the Wazalendo of accepting to be used as an anti-M23 militia, replacing the Congolese army whose efforts in fighting the Tutsi movement leave a lot to be desired. We need to go back to using the painful, though precise term, which emerges in a context in which the Rwandan mini-invasion updates the worst ethnicization of the denomination of the regional political vocabulary. The traces left by the war of the years 1996-2007 remain visible and are still experienced. We have come to a point where, from violated agreements to unenforceable sanctions, from sporadic massacres to ignored territorial violations, the international community shows, more than anything, its hypocrisy and its profound indifference. (Open Photo: M23 rebels. CC BY-SA 2.0/ Al Jazeera)

Gérard Prunier