Rwanda. Twenty-five years after Apocalypses. A transformed country.

Twenty-five years after the genocide of the Tutsis in 1994, the country is peaceful and the economy is booming. But citizens are striving for more freedom.

September 1994. Two months after the end of the genocide, the capital, Kigali was offering a picture of sadness and devastation. The windows of most government offices were broken. Electricity was off and shootings could still be heard here and there during the day or the night. Dogs were shot systematically because they had become dangerous since they had tasted human flesh. At the entrance of the city, the military searched vehicles for weapons. Hutu “Abacengenzi” (infiltrated) rebels were still active in the country.

In the neighbourhoods of Kigali, the disgusting stink of decomposed corpses was still floating around. I remember to have seen putrefied bodies including a child’s one lying in the bed of a small creek near Gitarama. On the hills which tower the fjords over Lake Kivu, in Kibuye, the stench of corpses which had been abandoned after a massacre occurred several months ago was making everyone sick. After the holocaust, which according a government count, caused 1,074,017 victims, including 934,218 identified ones, the entire country was to be rebuilt. Over two million people who had been forced by the army of the genocidaires to cross the border, were crowding the refugee camps in Congo. The most difficult task was to cure the invisible but deep wounds of widows and orphans.

Twenty-five years later, the transformation is radical.

Kigali, which once looked a calm provincial town, has a totally new skyline, with business centres and high building all over the place. Five-Star hotels raise their towers in different part of town. In the centre, the former headquarters of the so-called “interim government” which masterminded the genocide, the “Diplomates” Hotel has been substituted by the luxurious Serena Hotel.

A few hundred yards from there, tourists are enjoying the swimming pool at the Hôtel des mille collines, without knowing that it had been used in 1994 as a tank for refugees who were then besieged by the dreaded Interhamwe militias. The town which is towered by the new Defence Ministry bunker has grown from 300,000 to over 750,000 inhabitants since 1994.

The expansion is owed mainly to rural exodus and to the arrival of many returnees from neighbouring countries. But the proliferation of houses, offices and industries has also meant land expropriation. Many inhabitants of small brick or corrugated iron houses have been relocated outside of town. The human landscape and its description have changed. Noboby speaks anymore about Hutus, Tutsis and Twas, the categories (ubwoko) which appeared on the IDs before 1994, which made much easier the killers’job. Nowadays, people describe themselves as “Sopecya” (survivors), “Dubaï” (former Tutsi refugees from the Congo or Burundi) or “Tingi Tingi” (Hutu refugees returned from Congo).

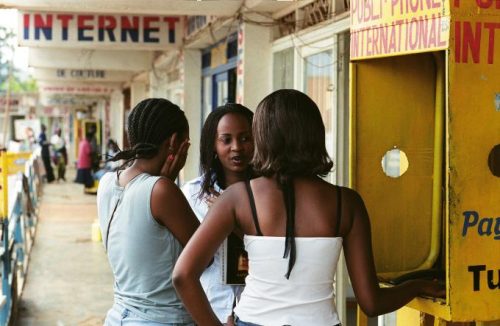

Kigali is now one of the cleanest and safest cities of the African continent. Plastic bags are banned everywhere. This deserved Kigali the Scroll of Honour awarded by UN-Habitat in 2008. This policy also allowed start-ups producing biodegradable items such as Jean de Dieu Kagabo’s “Soft Packaging” to emerge. The security feeling has completely changed for the good. In capital, where machetes and grenades caused terror, it is frequent now to see ladies including expatriate ones jogging at night. Markets look prosperous and both imported and local products can be found in abundance.

Most observers admit that President Paul Kagame has managed to restore stability in this devastated land. Efficiency against corruption is recognised internationally. State officials are accountable and must sign performance commitment with specified targets, the “imihigo”. In 2015, Rwanda met almost all the Millenium Development Goals. In ten years, one million people emerged from acute poverty and the country now boasts from an annual GDP growth rate of 7.8%. Yet, poverty has not been completely eradicated. The Agazoho Genocide Widows Association (AVEGA) is trying to assist women which the genocide turned overnight in the head of the family.

Over 95% of the children have access to primary school. Infant mortality decreased by 61% and three quarters of the Rwandans have access to safe drinking water. Women account for 55% of the members of parliament, which is a world record. And the country is one of the few in Africa to enjoy a universal social security system.The ambitious objective to achieve a 563 MW generation capacity by 2020 will not be met. But the country boasts from pioneer infrastructures such as methane gas and peat power stations. It is now considering to harness its geothermal potential. A new hydroelectric power station was inaugurated on the Nyabarongo River. The target is to achieve universal access to electricity by 2025 (as against 34.5% in 2017).

Rwanda has become the epicentre of digital Africa. The small landlocked state is banking in new technologies to create a business friendly environment for investors and ranks already second in Africa, in this category, according the World Bank. In June 2018, Volkswagen was seduced and opened a 5,000 cars assembly plant which produces Passat and Polo models.

A new generation of entrepreneurs has emerged. It boasts from a “knowledge laboratory”, a kind of incubator in Kigali. There is innovation in all directions. The Ikirezi Natural Products company produces citronella, geranium and eucalyptus essential oils for the perfume industry which represent a three-fold increase of revenues compared to the traditional production of beans. A drone airport was also built at Muhanga, to the South-West of Kigali,to transport blood samples, medicines and emergency equipment between remote areas of the country and hospitals. After the Kigali Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), a brand new Kigali Innovation City has just been set up and is scheduled to train 5,000 engineers per annum. The country has become a symbol of excellency for coffee, tea and cut flowers crops. Huge plans are on track to open up this land-locked country to the outside world. In January 2018, Paul Kagame and the Tanzanian President John Magufuli agreed to build a 400 km railway line between the two countries which will improve Rwanda’s access to the port of Dar-es-Salam. Yet, important efforts are still required.

The European Network for Central Africa coalition of NGOs admits that production and yields have increased over the last ten years. But accordingly, farmers should be more consulted in the process of definition of agricultural transformation strategies. Indeed, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation, 4 million Rwandans are still affected by malnutrition. On the meantime, technological can be noticed in the country side. Along the roads, yellow pickets indicate the presence of 4G cables. And the province towns of Kibuyé and Gisenyi also show a construction frenzy.

But at times, one feels Rwanda is still in the middle of a stormy area. Near the Nyungwe forest for instance, military patrols can be seen every two miles, reminding of tensions with neighbouring Burundi. There are still 79,000 Congolese refugees in the country, spread in camps near Butare and between Gisenyi and Kigali. And the authorities want to make clear they stand ready for any kind of threat. At the beginning of the year, a What’s App video was showing Kagame in uniform attending with other officers an artillery exercise.

There is a flip side of the coin, though. Time and again, human rights organisations complain about violations and insufficient press freedom. There is no doubt that opponents are given a hard time. In the past, several were assassinated. That was namely the case of the former Minister of Interior, Seth Sendashonga who was killed by a death squad in Nairobi in 1998. In January 2014, came the turn of the former chief of foreign intelligence, Col. Patrick Karegeya who was found dead in a hotel room in Johannesburg. Many Rwandans would like Kagame to open up the political space but few dare to express loudly such will. There is fear of repression and that open debate might bring back the devils of hatred speech and ethnicism.

François Misser