Postcard from Ghana. The Culture of Sewing.

Sewing and fabrics speak of Ghana, not only for the millions of dollars that the sector generates every year but also for how deeply this tradition is rooted in every corner of the country. Cities like Kpando, where workshops invade the streets, are proof of this.

In Kpando, a town of about 28,000 inhabitants located in the Volta region, there are two activities that stand out above all: hairdressing salons and sewing workshops. If it is true that the former passes a little more unnoticed, the importance of the latter is such that the inhabitants of this city can find up to 20 stalls of tailor-made clothes on its main street alone. In fact, there is one shop for every 280 inhabitants.

Xorlali operates the wheel of the sewing machine as if she has done it all her life, but it’s only been two years since she finished her apprenticeship. “I was taught a lot of theory at school, but I needed to touch it with my hands”, she recalls as she traces a pattern on a suit.

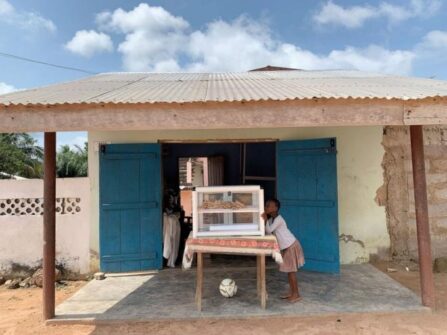

Amidst piles of scraps and plastic bags full of unused fabrics, the 23-year-old works hard to become, as she says, “the best seamstress in Kpando”. Her workshop has no windows, but it does have a large door that opens onto the street.

Surrounded by these four walls, on just over five square meters, Xorlali sews clothes and takes orders from dozens of customers.

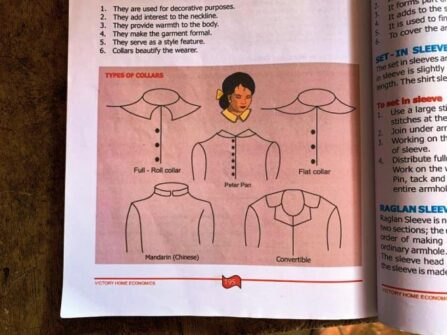

Textile production is a very important sector. So much so that in the Delta Preparatory School textbooks, also in Kpando, there are topics and themes dedicated to sewing. From the different types of sleeves to the making of different collars to the main tools and steps to follow to how to darn. The program is part of a design and technology subject where boys and girls also learn technical drawing and some traditional cooking recipes.

Unsurprisingly, sewing workshops take up most of the city’s kiosks. They are small structures, built with iron sheets or bricks, with colourful and eye-catching facades. Inside, posters show dozens of models wearing different garments, most of which are made of kente, the country’s most famous fabric.

Illustration from a textbook showing different types of garments. (Photo: Margalida Fullana Cànaves)

“It is very common for someone walking down the street to ask you who made the dress you are wearing”, says Xorlali. Unlike the capital Accra and the second most populated city, Kumasi, it is difficult to find ready-made clothes in Kpando. However, you can buy fabrics of a thousand colours for around a dollar a meter. “I love it when someone says I’m his tailor and recommends my work”, adds Xorlali with a big smile.

Ghana is one of the largest textile exporters in the world. According to the latest data gathered by the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), the country exported about 53.5 million dollars in this sector in 2019. About 27.9 million, to the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, while another 18.4 million to North America. Europe and Central Asia account for approximately 1.9 million dollars.

Xorlali’s workshop. (Photo: Margalida Fullana Cànaves)

With the needle moving at full speed, Xorlali points out that she usually charges around $4 per garment, “Isn’t that very cheap?”, she complains with wide-open eyes, aware that her profit will increase as she gains experience. She buys the fabrics she uses for his work from some stalls in Kpando Centre, but doesn’t know where they come from. “I think they come from Accra”, she says without thinking.

Serafine, on the other hand, is a 50-year-old woman who runs a small fabric shop in the local market of the city. She sits on a small plastic bucket, accompanied by one of her three children. Her stall, which only has room for about 50 fabrics, is located in one of the narrowest aisles in this large bazaar. Amidst the intense smell of spices and dried fish, her stall, which does not even have a light, goes almost unnoticed.

“I go once a week to Accra and once a month to Lomé’ the Togolese capital to buy fabrics”, says Serafine where she buys 50 to 60 pieces of fabric, each about six meters long. You travel to these cities by car or by trotro, as buses are called here. She usually shops in department stores, where the fabrics are made of cotton. “Even if the fabrics are quite similar, those from Togo are cheaper”, she explains.

Serafine says that since the beginning of the pandemic, entry into Togo has been more difficult than usual. “Some of the main border crossings have been closed and we are now forced to cross the border on secondary roads”, she explains. She also tells us that although the police routinely carry out security checks upon entering and exiting the country, there is no maximum number of meters of fabric that can be transported, so she tries to make the most of each trip.

But of the 100 sewing workshops on Kpando, one stands out above all: that of Anita, a 30-year-old woman who decided to open her own business in 2017. “I started sewing in my room, at my parents’ house, and I now have about 18 employees”, she reveals.

Her workspace is almost on the outskirts of Kpando, but it doesn’t go unnoticed. She has 16 antique sewing machines, these are for apprentices, “but the more proficient sewers use these others”, she says, pointing to a set of nine electric sewing machines.

Anita’s workshop workers with the electric sewing machines. (Photo: Margalida Fullana Cànaves)

“Everyone has their own preferences – Anita adds. I want the people who come to my lab to be serious and appreciate what I do”. That’s why she, unlike Xorlali, can charge up to $120 for an elaborate dress, including fabric and beads. Her shop is not only the most expensive in Kpando, but it is also the sewing workshop where the most privileged people go when they need clothes for special occasions such as funerals. Anita says: “There is a very detailed dress code: if the deceased is over 90, you have to dress in white; if he is between 75 and 90, black and white; and if he’s under 75, black and red.”

As she speaks, she looks towards the street where a very elegant young woman is chatting with another lady. “See that dress, I made it last week. The people on the street with my clothes are my advertisement”.

Margalida Fullana Cànaves