Music. Tiken Jah Fakoly. The star of African reggae.

With his latest work the Ivorian artist, who has lived in Mali for years also for political reasons, gives new voice to 13 flagships of his career. A path that took him to the top of the continental reggae scene.

Emerging in the 1960s, reggae was welcomed promptly and with great enthusiasm throughout Africa. But Ivory Coast in particular has established a special harmony with this genre. If there has been no shortage of important African reggae protagonists of other nationalities, such as the Nigerian Majek Fashek (1963-2020) and the South African Lucky Dube (1964-2007), in half a century of reggae in Africa two great stars stand out, and they are both Ivorian , Alpha Blondy and Tiken Jah Fakoly: both with an international reputation, but on the global reggae scene the long-standing star of Tiken Jah – whose sixteenth album, Acoustic (label Chapter Two/Wagram Music) has just been released – has become brighter even than that of an extraordinary pacesetter

of African reggae like Blondy.

Tiken Jah Fakoly’s success took off with the 1996 album Mangercratie; at the time, in the convulsions of the post-Houphouët-Boigny period – the father-figure of independent Ivory Coast – Ivorian reggae, with Alpha Blondy at the head, valiantly took a stand against xenophobia, used without scruples, in the delicate Ivorian ethnic kaleidoscope, for power scheming: and in Mangercratie Tiken Jah pointed the finger at the cynicism and irresponsibility of politicians.

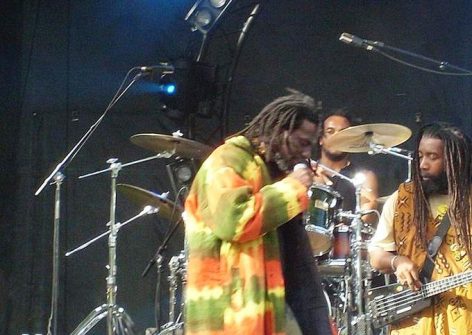

Tiken Jah Fakoly performing at Ancienne Belgique, Brussels. CC0 1.0/ VerwimpBruno

Born in 1968, at the age of eight Tiken Jah began listening to Bob Marley, and when he died in 1981, he cried; in the eighties, Blondy, born in 1953, had established himself, and Tiken Jah had learned from his talent as a singer, and treasured the example he offered of conscious, committed, denunciatory reggae. Threatened with death in the torn Ivorian context, Tiken Jah has been living in Mali since 2003, from where he brilliantly continued his career, and where he decided to stay despite the difficult situation that the country has been experiencing

for about fifteen years.

With the addition of a new song, in Acoustic Tiken Jah dusts off in an acoustic version thirteen workhorses from his discography, around a quarter of a century of production between the albums Mangercratie and Braquage de pouvoir released in 2022: it is therefore a sort of self-anthology, which lends itself both to a summary of his work and to a first approach for those who do not know him.

“I protested against racism, tribalism, but it was no use. (…) I have the impression of preaching night and day in the desert. (…) I’m tired, I’m tired”, sang Tiken Jah Fakoly in Délivrance, a song included in Mangercratie and re-proposed in the new album: however disillusioned, the Ivorian singer actually never fell out of love with the role he gave himself with his reggae, that of “awakening consciences”, and has not stopped making his voice heard.

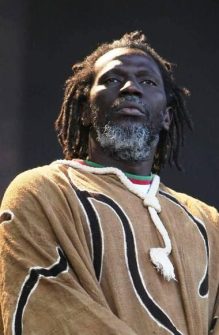

Tiken Jah Fakoly at the Eurockéennes de Belfort (France). CC BY-NC 3.0/Rama

His next album, in ’99, was Cours d’histoire, “Course of History”: a challenging title for an artist who feels the responsibility of a name that is equally so, and one that has been consigned to history.

Born Moussa Doumbia Fakoly, Tiken Jah is in fact a descendant of Fakoly Koumba, who according to tradition in the thirteenth century, siding with Sundjata Keita, played a significant role in the military victory that was the basis of the birth of the glorious empire of Mali.

In Acoustic, from Cours d’histoire Tiken Jah takes up among other things Les Martyrs: «They have forgotten that they tortured, that they murdered, that they humiliated – among the various martyrs he names is Thomas Sankara – we will forgive but we will never forget”. Tiken Jah then continued to impart authoritative history lessons, which many young people, especially from West Africa, have listened to, and here he offers an anthology: in Plus rien ne m’étonne and in Tonton d’America he talks about who it was who divided up Africa and still casually divides up the world and of the uncle from across the Atlantic who takes advantage of the miseries of the black continent, while in Ça va faire ill dreams of an Africa finally united and capable of facing the arrogance of the developed countries (all three of the songs are taken from the 2004 album Coup de gueule); un Africain à Paris – Sting’s version of an Englishman in New York – he puts himself in the shoes of a son who writes to his mother, and it is an implicit invitation to Africans to stay at home, but in Ouvrez les frontières (“Open the borders”), he recalls the injustice of preventing Africans from entering Europe, while Europeans can enter Africa whenever they want.

Tiken Jah Fakoly in concert. CC BY-NC 3.0/Dieudo

Tiken Jah Fakoly has a direct and wise way in presenting his lyrics, which are simple, and therefore incisive: but being simple is not easy. In Délivrance, Tiken Jah also said: “We were optimistic, we dreamed, we hoped, but nothing has changed”; almost thirty years later, here, in the only unreleased album, Arriver à rêver, the need to dream has not yet abandoned him, and Tiken Jah finds the simplicity to say: “We will have to succeed, be able to dream, succeed, yes, to succeed, in the end, to truly change the world”. (Open Photo: Tiken Jah Fakoly, singing in a SABC recording studio in Johannesburg. 123rf)

Marcello Lorrai