Music. Aziza Brahim sings Sahrawi time.

Her sixth album, Mawja, returns to traditional sounds, reconnecting the Western Saharan artist with the stories and rhythms of her family. And to the struggle of the women and people of this land of conflict.

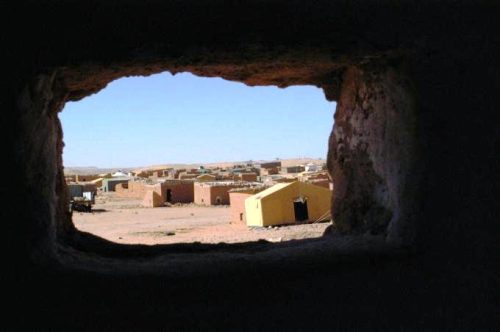

Aziza Brahim was born in 1976 in the Hammada of Tindouf, a Sahara Desert plateau in western Algeria nicknamed “the Devil’s Garden” for its inhospitality. Over 173 thousand Sahrawis have lived here for 48 years, living in exile in refugee camps located in the autonomous areas of the Tindouf Wilaya. Recognized as the voice of the Sahrawi people, we met Aziza Brahim on the occasion of the release of her sixth album Mawja:

a 10-track project produced by the label specializing in world

music Glitterbeat Records.

Over 173 thousand Sahrawis have lived here for 48 years, living in exile Hammada refugee camps located in the autonomous areas of the Tindouf Wilaya. File swm

How and when did you realise that music would be your way of life?

I was 6 or 7 years old when I discovered that I could sing, that I had a voice capable of entertaining and pleasing spectators. My maternal grandmother organized “competitions” at home where she and my mother were part of the jury and in which all the boys and girls of the family participated. I worked very hard during the performances.

The fact that I won them all made me think that maybe my voice was acceptable. But only a few years later, in Cuba, when I was the lead singer of the school band, did I begin to think about dedicating myself to music professionally.

“My commitment to spreading the Sahrawi cause” File swm

What inspires and influences you?

My maternal grandmother Ljadra Mint Mabruk [ed. internationally renowned poet and activist for Sahrawi liberation and self-determination] was my first ever influence. She has always motivated my creativity by challenging me to put her verses and her poems into music.

She was a real school for me, a source of learning also as a person due to her tenacity, conviction and pride. Regarding the artistic aspect, she conveyed to me her pleasure in poetry and music. Furthermore, I assimilated many musical influences from the old haima radio [ed. haima is typical Sahrawi tent] of my grandparents.

Are you committed to making the Sahrawi question known?

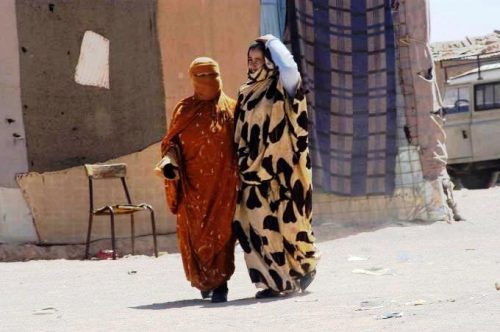

My commitment to spreading the Sahrawi cause is very simple: it consists of being and singing as a Sahrawi. Every daily act for us is a political act. Our way of speaking, our way of dressing, and our sense of belonging to the community are all political acts. Of course, I faced multiple obstacles in talking about it. Moroccan censors, for example, have sometimes tried to hinder my concerts.

“I sing to reaffirm the power of women”. File swm

How do you think the Sahrawi cause is treated and addressed at a global level?

The Sahrawi population has been in the refugee camps of Hammada, one of the most inhospitable deserts in the world, for almost 50 years. We live in haima or precarious buildings with serious shortages, no comfort, in minimal conditions. After the Covid-19 pandemic, international aid has greatly reduced. The situation is increasingly difficult for the refugee population.The international community is incapable of finding a solution: it seems that interests are more important than rights! I think that the major mass media do not want to inform about the Sahrawi struggle because it is not in their media interests. In my opinion, we must try to put this conflict under the spotlight because there is an entire population in limbo that suffers due to the silence, passivity or oblivion of the world political class.

Tell us about your latest album Mawja…

The creative process of Mawja’s songs helped me a lot to come out of a deep anxiety crisis. We may translate Mawja as Wave. It’s the word my grandparents said when they turned on the radio we had in the haima. The main themes are the passage of time, the tension between past and future, and the situation of the Sahrawi people. I wanted to pay homage to my grandparents’ great haima, the place where I was born and raised. Furthermore, I dedicated a prayer to my grandmother Ljadra Mint Mabruk [ed. Duaa], who passed away in October 2021. I sing to reaffirm the power of women, to remember the Sahrawi games of my childhood and the mythical bird Bubisher who brings good news to my culture.

“We may translate Mawja as Wave.”

Mawja is a return to simple songs, far from the electronic elements I played with in Sahari [2019]. There is a mix of traditional and modern instruments of roots music. I fused rhythmic elements of my Sahrawi culture with Iberian, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern and West African musical traditions. There is a profound fusion in this album between different types of traditional music. For example, different flutes are used: the ney, the Chinese hulusi and the Aymaran mohoceño. These traditional elements are then joined by more contemporary sounds and instruments such as the electric guitar, the drums, the double bass or the flamenco tres: a new instrument created by Raúl Rodríguez, an excellent Andalusian guitarist who plays it in the song Haiyu ya Zuwar. (Open Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0/Elekes Andor)

Nadia Addezio