Nigeria. Avocado, the black pear.

Some African countries are on their way to becoming the main avocado exporters of the future due to the particularly favourable environmental conditions of the continent. The crop may take the place of coffee and create more jobs.

The avocado is certainly one of the food products more in demand in the West in recent years both for its culinary and aesthetic properties. The Latin American countries are the main exporters. There, the avocado is seen as nothing less than ‘green gold’ and it is a source of riches for the regional economy but it has come to be the symbol of environmental degradation and the exploitation of the cultivators. Recently, the market for this fruit has been expanding also in the African continent with modalities that are completely different from those of Latin America and give reason to hope for a mode of production that is both profitable and eco-sustainable. In Africa, in fact, the avocado is cultivated on small farms in areas of high rainfall that renders unnecessary the use of harmful pesticides and avoids creating water supply problems

for the local population.

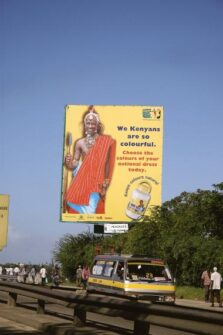

Kenya is already among the top ten producers in the world, while other African countries have only just discovered the characteristics of this new crop. This applies to Nigeria where there are fields of various species of avocado, especially in Plateau State, but trade is more international than local. This is due to different factors, one of which is the lack of information among the population which is reluctant to cultivate a plant that takes several years and a lot of water before producing fruit as compared to cultivating maize and potatoes. Furthermore, starting a cultivation of avocado trees often requires imported seedlings which raises the cost of production. However, some cultivators have established themselves in this new sector and are collaborating with the Nigerian government to sensitise public opinion about the avocado, the modernisation of the agricultural system, rotating various crops so as to render the soil more productive.

The Avocado Society of Nigeria (AVOSON) is the main organisation at the national level devoted to developing the avocado market, guaranteeing the integrity of the environment and new jobs for the citizens. Besides various training projects, AVOSON also promotes outlets for the sale of seedlings so that the small farmers do not have to pay high prices for imports. There are still, of course, many questions to be answered, the first of which regards the effect of climate change on rainfall and the model of the future development of Nigerian farms, but at present there seems to be a real possibility of a new market for the country

and the surrounding region.

An alternative to coffee

Even though the export of agricultural products was, in the sixties, the largest source of income for Nigeria, since the seventies, agriculture has been neglected in favour of the petroleum sector. Only in recent years, due to the collapse of oil prices, is agriculture emerging from a long period of stagnation.

The government is now aiming not only to increase agricultural production but also to diversify and modernise it. In this context, the role of the avocado is becoming increasingly important. Coffee is another agricultural product that has been present in the African market for many years. Like the avocado, it is produced for export rather than local consumption. The African coffee plantations face strong competition from Latin American countries known for the excellent quality of their coffee as well as climate change due to which rainfall has become unreliable and endangers the fields of millions of African coffee cultivators. The government is therefore making investments to develop new techniques of coffee cultivation as well as diversifying production while relying on avocado plantations.

Former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo (L) holding an Avocado while speaking Sola Adeniyi, chief executive officer, of Avocado Society of Nigeria. (Photo Business Day).

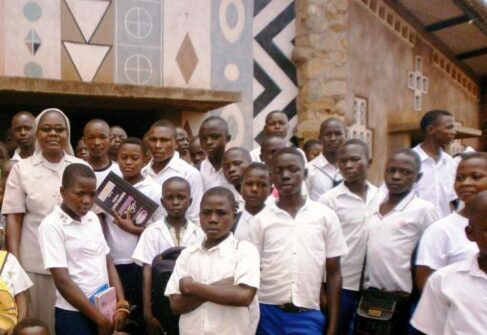

Former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo defined the avocado as ‘the new Nigerian oil’ during a meeting of the Avocado Society of Nigeria and hopes that the country will become its largest exporter before the end of 2030. Income from the export of this fruit increased by a third from 2019 to 2020 in eastern Africa. The ‘African pear’ – as the fruit is sometimes called in the continent – is being seen not only as an antidote against malnutrition and some diseases but also against poverty since it creates work for many of its citizens. The schools are also providing information about this fruit so rich in beneficial properties, and the government is enthusiastically supporting initiatives in the sector, confident that the hopes of the former President may be realised.

Alessandra De Martini/CgP