Religion & Family.

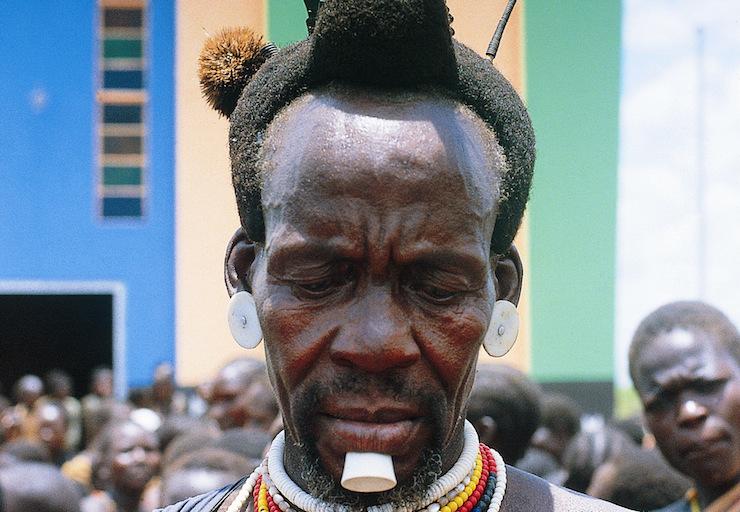

Prior to the Christian missionary movement in the 19th century, the Ankole people’s idea of a Supreme Being was Ruhanga (creator) who was believed to be living in the sky. He was believed to be the maker and giver of all things.

However, it was believed that evil persons could use black magic to interfere with the good wishes of Ruhanga and cause ill-health, drought, death or even barrenness in the land and among the people. It is believed by the people of the land that Ruhanga created humanity in the form of a man called Rugabe and his wife Nyamate. Rugabe and Kyamate gave birth to a long line of kings who became deified. These gods had special temples and priests often in the royal compound, and tended to be concerned with helping people to solve special problems. These were for instance: a god of fertility, a god of thunder, a god concerned with earthquakes, and the deities for specific clans and their affairs.

The Banyankole generally believe that illness is caused by Ruhanga, ghosts, or magic. Ruhanga is said to cause illness and ultimately death because his desires and rights have not been fulfilled and adhered to. A ghost causes illness if cows dedicated to the family are sold or bartered without the consent of the ghost, if offerings due to him are not made, and if clan laws are violated.

A hostile ghost from another clan can cause illness. If a person has a grudge against another person, a magic rite may be performed over beer, which is then offered to that person to drink. Once a person discovers that he has drunk such beer, he or she dies of fear.

The aspect of the Kinyakole religion that still exists today, is the belief in ancestral spirits. It is still believed that many illnesses result from bad behavior to a dead relative, or to Ruhanga, and especially paternal relatives. Through divination it is determined which ancestor has been neglected so that presents of meat or milk, or change in behavior, can appease the ancestral spirit in order to address the misfortune spiritually. The Banyankole (people of Ankole) respect ancestors and name children after them. They also believe the dead can communicate to them through dreams, warning them or directing them about something. Few Banyankole believe that death is a natural phenomenon. According to many, death is attributed to sorcery, misfortune and the spite of the neighbors.

They even have a saying: Tihariho mufu atarogyirwe, meaning; ‘there is no body that dies without being bewitched’.

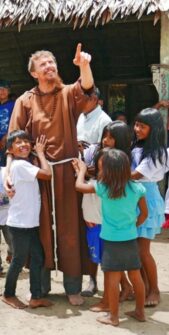

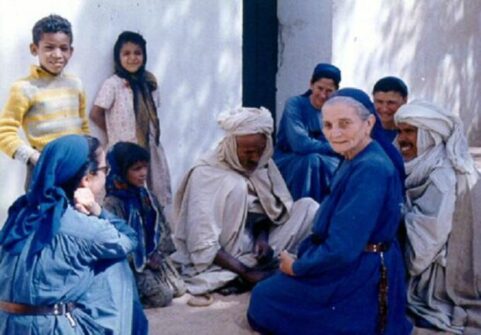

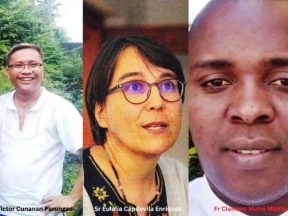

Today many Banyankole are Christians, Anglicans and Catholics, with some Seventh Day Adventists and Muslims.

Family life

The Banyakole home was designed creatively for accommodation, interaction and hospitality to promote family values, respect among society members and a place for co-creation.

The success of the family was based on the type of a home one had and the entire set up of the homestead.

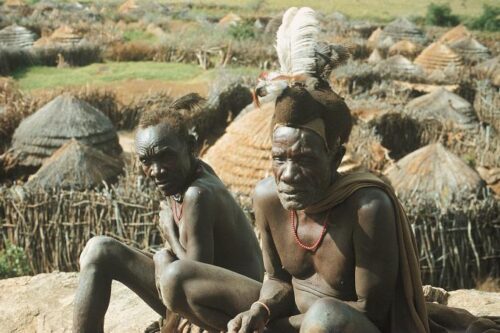

The Banyakole never stayed in one place because they kept moving from place to place in search of resources that favored their livelihoods; they lived as either cattle keepers or crop cultivators. Houses were round and temporarily built with organic materials, especially flexible trees, thatched with grass. And the houses could be kept as long as the family would be in one location.

The house was divided mainly into three parts: the living room that contained the Orugyengye (milk pot platform); the living room also containing the father’s stool, which was a greatly respected item. Whenever children sat on it innocently, they would be rebuked by their mother because it was sacred. Other than sitting on it, the stool was either to bless or curse. The other part of the grass thatched house was the Ekitabo Kyabana (children’s bedroom), and the Ekitabo Kyanyineka (the master bedroom). The house provided a space in the master bedroom for keeping important items such as the spear and other household goods and valuables.

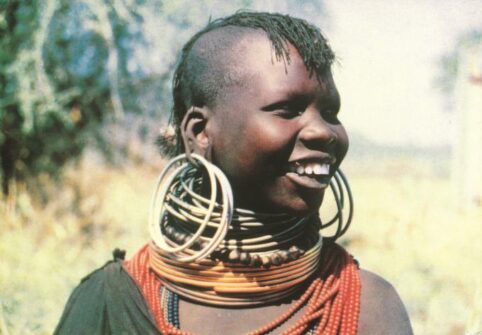

And as such, a home design set up a hospitality venue where families entertained visitors. Traditionally, households were set up on an extended family model whereby visitors were expected anytime. As such, visitors had a special stool, especially the elders. The interior of the house was covered with eyojwa (soft grass) with well-trimmed animal skins laid on top on which young people and women would sit.

The common practice among Banyakole homes was the okuterama (vigil) which was a practice where young men and women would gather at the house of the families, tell stories and share happy moments. This practice compelled families to construct large houses so as to allow as many people as possible to enter during okuterama. Light and warmth for members was provided by the fireplace which would remain burning in one corner of the house or outside. The fire was tended carefully so as to avoid spreading which could burn the house.

The Cattle.

In Ankole, cattle were and are still the most treasured possession in the people’s lives, providing milk, ghee, beef and hides; cows were a state of value and a medium of exchange. Cows were and still are the mode of payment of the bride-price and some special cows were used in religious rituals as well as cultural and political ceremonies. The long horned Ankole cows are still the most valued because they are adapted to the climate of the region and resistant to most diseases. A cow was appreciated for the amount of milk it yielded, for its size and stature, its body color and for the shape and whiteness of its long horns, as well as its ancestry. (G.L.M.)