The construction of a gas pipeline linking Nigeria to the southern coast of Europe could change the European Union’s energy balance, making it less dependent on Russian gas. However, the large-scale project faces several challenges and raises numerous questions, some arising from the complex situation in West Africa.

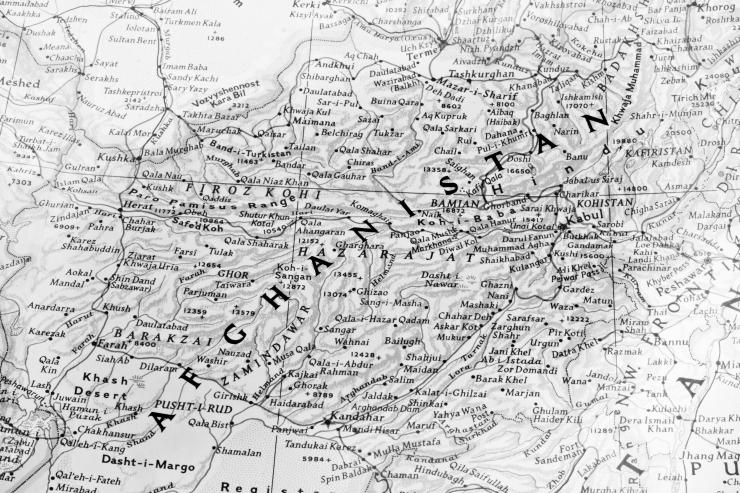

The first issue concerns the infrastructure route, for which there are two alternatives. The shortest route proposes a 4,000-kilometer route from Nigeria to Algeria, through Niger and the Sahara Desert, to connect to existing gas pipelines on the Algerian coast.

From there, it would have to be decided whether the gateway to the European Union (EU) would be in Italy or Spain.

The second alternative envisages travelling over 7,000 kilometres of the West African coastline, of which 5,660 are underwater and another 1,700 over land, as far as Morocco, where the gas would enter Europe via Cadiz (Spain). Although distances are important in the balance, there are several factors to consider in discerning the route that best serves the interests of Nigeria and the EU, and the main actors in a project that would benefit Algeria and Morocco depending on the route chosen.

Gas pipeline under water. The second option is to travel along 7,000 kilometres of West African coastline. 5,660 of these kilometres are underwater. Shutterstock/Marko Aliaksandr

By signing bilateral treaties with the two Maghreb countries, Nigeria has sought in recent years to encourage competitiveness between the two nations, albeit with an air of chaos and uncertainty about the final outcome.On January 24, 2024, the Executive Vice President of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), Olalekan Ogunleye, and the Director General of the National Office of Hydrocarbons and Mines of Morocco, Amina Benkhadra, met to discuss the progress of the contract awarded by Nigeria in 2022 to Worley Energy for the design of the main engineering of the Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline.

But a month earlier, in December 2023, Nigerian Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar said that the pipeline linking Nigeria to Algeria had made “significant and noteworthy progress.” According to recent reports of the Nigeria-Algeria pipeline, which would be able to supply Europe with 30 billion cubic meters of gas per year, “only 100 kilometres remain in Nigeria, 1,000 in Niger and 700 in Algeria”.

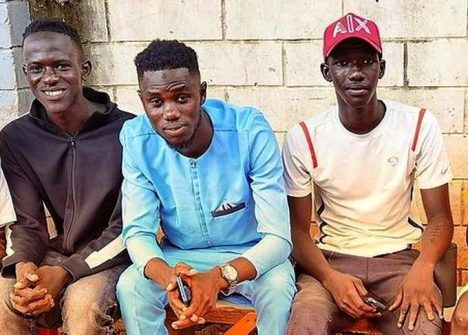

The Group Managing Director of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), Mallam Mele Kyari. An investment of 25 billion dollars would be in place for the Moroccan option. Facebook

The agreements signed by Abuja and Algiers appear to have a more official character thanks to the participation of high-level officials, as in the case of the signing of a treaty between the Nigerian and Algerian Energy Ministers in 2022, although in October of the same year the director of the National Nigerian Petroleum Company Limited, Mele Kyari, indicated that by the end of 2024, an investment of 25 billion dollars would be announced for the construction of the Moroccan option.

The Islamic Development Bank has also agreed with the Moroccan Ministry of Economy to finance a feasibility study of the pipeline for 90 million dollars, while the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has committed to financing the second phase of the study with 14.3 million dollars. The Moroccan project also involves, among others, the global consultancy firm ADVISIAN, which is in charge of exploring energy self-sufficiency in the region. This sleight of hand between Nigeria and Morocco and Algeria makes it necessary to analyse both alternatives to verify their feasibility and the benefits they can bring to the European energy market.

From Nigeria to Guinea

The Moroccan project calls for the pipeline to run along the coasts of 11 African nations – Benin, Togo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, Senegal and Mauritania – plus Western Sahara. Some have suggested that this route could be used to supply gas to the aforementioned territories. Currently, a 678-kilometer stretch between Nigeria and Ghana is in operation, owned by the West African Gas Pipeline Company Limited, whose shares are held by Chevron (36.7%), Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (25%), Royal Dutch Shell (18%), Volta River Authority of Ghana (16.3%), Societé Togolaise de Gaz (2%) and Societé Beninoise de Gaz (2%).

Oil pipes and valves. The Moroccan project calls for the pipeline to run along the coasts of 11 African nations. 123rf

In this option, the first challenge concerns Nigeria. For decades the country has been experiencing a security crisis that affects almost its entire geography, due to the jihadist threat in the north, the conflict between herders and farmers, plus kidnappings and piracy that is rampant in the Niger Delta and the Gulf of Guinea. In this enclave and at the mouth of the river, where some of the main oil extraction facilities are located, bandits have been operating regularly for decades, stealing crude oil to sell on the black market, a practice that Nigerian security forces have not been able to eradicate.

Relations between Nigeria and its western neighbour Benin are highly dependent on Nigerian consumption. Although there have been moments of tension, such as when Abuja closed its border with Porto Novo between 2019 and 2021, the two countries are currently collaborating in Operation Prosperity to combat piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Although the results have been positive, everything suggests that the intervention of European or US forces would be necessary to ensure the protection of these infrastructures in the area.

President of the Ivory Coast, Alassane Ouattara. Regional leadership is being contested by Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria. Photo: US Dep.

The Ivory Coast, through which the pipeline would pass, could benefit from the project for the possible supply of gas it would receive, but President Alassane-Ouattara is not unaware that a pipeline of this scale would represent a major economic and geostrategic boost for Nigeria, a nation with which the Ivorians are competing for regional leadership.Although the civil wars in Sierra Leone and Liberia are now far away, neither country is a stranger to the delicate situation in the region. Sierra Leone suffered an attempted coup in August 2023 and the Liberian elections of the same year, in which Joseph Boakai won, highlighted the political and social tensions in the country.

The equation is complicated in the Republic of Guinea, where Colonel Mamady Doumbouya has ruled since the 2021 uprising. The military officer has barely changed Guinea’s foreign policy since coming to power and maintains close trade relations with Russia while tending to collaborate with Sahelian countries governed by military juntas. Although Guinea is not part of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), Doumbouya’s reliability in a project of the scale of the pipeline is questionable.

Difficulties and questionable partners

The complications continue in Guinea-Bissau. Its 88 islands serve as a gateway to Africa for cocaine from South America, which leads to high levels of violence and corruption in the country, governed by Umaro Sissoco-Embaló. The situation is unstable on the streets which are patrolled by Senegalese and Nigerian soldiers on an ECOWAS mission. The main opposition leader, Domingo Simões Pereira, has expressed his firm opposition to the pipeline. If he wins the next presidential elections, to be held this year, his position could make it difficult for the pipeline to pass along the coast of Bissau.

Senegal may be considered be one of the most reliable partners for the project thanks to its excellent relations with Morocco and Nigeria, but the election of Bassirou Diomaye Faye in March 2024 makes the future unclear. The Senegalese president included in his speech the break with French neocolonialism and European interference, in addition to announcing the intention to develop new models of cooperation with Russia, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey. In addition, his ideological proximity to the military juntas of the Alliance of Sahel States undermines Senegal’s credibility in undertaking a project that requires sustainable relations with ECOWAS and Europe.

The presence of gas in Senegalese waters has led to a slight deterioration in relations with Mauritania. File swm

The discovery of natural gas reserves in Senegalese territorial waters means that its interest in Nigerian gas is not urgent. Abuja and Rabat should convince Dakar to propose an alternative that would allow the outlet of Senegalese gas through the same pipeline, thus linking Senegalese energy development to the feasibility of the project.

The presence of gas in Senegalese waters has led to a slight deterioration in relations with Mauritania, while Morocco’s relations with Mauritania are unstable due to Rabat’s expansionist policy in the Western Sahara conflict. Although many members of the Polisario Front are located in the Mauritanian desert, the country officially maintains a position of “active neutrality”.

The economic incentive that a gas pipeline would bring to Morocco would strengthen its position on the regional chessboard, a reality that does not necessarily fit with Mauritanian interests.

The flag of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Saharawi activism is showing strong opposition to the project. File swm

The Saharawi question also raises doubts. The recent ruling of the High Court of Justice of the EU, which ruled in favour of the Polisario Front and annulled the agricultural and fishing agreements signed with Morocco because they did not include the Saharawi people, could represent an obstacle to the project. The need to delimit Saharawi territorial waters meets the first dilemma in Morocco’s fisheries policy. In the current context, it is unlikely that the construction of a gas pipeline through Saharawi waters can be completed in a consensual legal framework. Giving Saharawi territorial waters to Morocco would be a serious blow to the sovereignty of the former Spanish colony. Alongside this factor, Saharawi activism is showing strong opposition to the project, undoubtedly supporting the Algerian route.

Then there is the economic factor since the cost of the pipeline is unknown and its construction could take 25 years. Although Morocco and Nigeria have assured that they will finance the project equally, it cannot be developed with the sole contribution of African states. Rabat and Abuja are counting on investment from the EU, whose willingness to support the infrastructure is essential for its viability.

The Algerian option

The Algerian route offers significant advantages over the Moroccan one. First, it would be quicker to build. In addition to the fact that a significant portion has already been completed, the distance covered by this pipeline would be shorter than that of the maritime pipeline. Although the desert weather conditions could pose logistical difficulties, they would be less decisive than those of an underwater pipeline.

The Algerian option seems to be the most sensible in economic terms, as well as the fastest, but three factors put its viability at risk.

The first is the Jihadist threat that is spreading in the Sahel. Armed groups are firmly entrenched in central and northern Mali, largely in Burkina Faso and southern and western Niger. A pipeline from Nigeria to Algeria must necessarily pass through southern Niger under the threat of attack. If jihadist groups expand their areas of influence in Niger, the construction of the pipeline along its geography would become an almost insurmountable security challenge.

Rusty sign, natural gas line, in the desert. The Algerian route offers significant advantages over the Moroccan one. Shutterstock/U. Eisenlohr

Another factor worth noting is the current relationship between the military junta in power in Niger and Europe. Since Abdourahamane Tchiani came to power in July 2023, French soldiers stationed in the country have been expelled along with the French ambassador, as well as US troops stationed at Base 201. The European training mission EUCAP, which has been ongoing for over five years, and the number of mining contracts between Western companies and the Nigerien government have been reduced in recent months. The position of the military junta is opposed to France and the West as a whole, while it has shown increasing interest in collaborating with Russia in every possible area: from energy development to military cooperation to mining.

The current situation in Niger makes the Algerian option virtually unviable. The risk is too high considering that the EU would finance the majority of the project and that there would be no second chance in case of failure. In this context, Europe finds itself in a difficult situation that suggests that neither option will be fully developed in the foreseeable future. Either it builds a pipeline worth billions of euros over a quarter of a century, thus extending its dependence on Russian gas and relying on more than a dozen African nations, or it builds a pipeline through a territory infested with armed groups and ruled by an anti-European military junta. Both options carry great risk. (Open Photo: Pipeline through the desert. Shutterstock/Mike Browne)

Alfonso Masoliver