Kenya. Nairobi’s thirst for a future.

Short of water and housing, with spreading criminality and a pandemic that seems difficult to bring to a halt, Nairobi is in search of a ray of light. With its lively underground scene fed by a young, dynamic society and a futuristic smart city plan, the Kenyan capital is trying to quench its thirst for a future.

Before the formation of the metropolitan area with more than ten million inhabitants, there was a vast swampy area where various peoples lived, the best known of which were the Maasai. It is from the Maasai language that Nairobi takes its name: enkare nyirobi, the land of cold waters. When the British arrived in 1899, it was necessary to open East Africa to colonisation, join the internal regions of the continent with Lake Victoria and the Indian Ocean. Nairobi was then founded at the beginning of the twentieth century as a railway depot for Uganda Railway. This marked the start of a population explosion from 25,000 inhabitants in the early twenties to 4.5 million today and an annual growth projection of more than 4% at least until 2030.

So little remains of those cold waters that, since independence, Nairobi has often had to come to terms with serious difficulties in providing water, due especially to the rapid rise in the urban population and a high rate of loss. The situation is so critical that, despite the large dam on the Thika River (with a capacity of 70 million cubic metres), the city is still exposed to the cycle of the seasons and only 50% of the population has direct access to the mains while 40% of the water is lost. Apart from the possibility of boosting the urban network, (64% financed by foreign donors according to USAID estimates), the government has launched a project to connect to the pipeline 193 wells dug by the Nairobi Metropolitan Services, a public entity, with an investment of 1.7 billion Kenyan shillings (about €13 million).

According to the Ministry of Water, Sanitation and Irrigation, Nairobi needs a further 260 million litres of water per day which, with the financial help of international institutions, the city intends to obtain by means of important infrastructure serving the entire metropolitan area, such as the Karimenu Dam (23 million litres per day) and Ruiru Dam (32 million litres), the Northern Collector Tunnel (140 million litres) and the Kigoro water treatment plant (140 million litres).

These projects could provide the Nairobi metropolitan area with more than 500 million litres per day, increasing the percentage of citizens with access to potable water which already rose from 72% to 76% in the last three years. While the shortage of housing has become a chronic affliction for the well-off western metropoli, the phenomenon assumes dramatic proportions in Nairobi. According to the World Bank, Kenya would need to build around 200,000 new homes every year to keep up with population growth but the situation shows a housing deficit of about two million units. As a result, Nairobi has an abundance of slums full of misery and poverty, with no essential services where conditions are ideal for the incessant spread of the pandemic which has already reached 70,000 cases in the city. The crisis is aggravated by the constant coming and going to and from the rural areas of the country from where thousands of people come to the capital in search of a better life.

Overcrowding in the slums of the periphery also contributes to the intensification of existing criminality, a very dangerous phenomenon for the capital of a country in the front line of the fight against international terrorism. However, the housing crisis has also been produced by the real estate bubble that has held Nairobi in its grasp for years. Around 75% of the workforce of the city earn less than 500 dollars a month and 91% live in rented accommodation due to high interest rates on loans. This creates a wide gap between those who earn enough to buy a house and to change the face of entire quarters. An example of this is the ongoing process of gentrification in Eastleigh, in the eastern part of Nairobi now in the hands of the Somali diaspora while the original population increasingly falls victim to authoritarian evictions enforced by the police as happened in the spring of 2020 when, from one day to the next, the Kenyan government removed around 8,000 people from the Kariobangi and Ruai. The urban and housing dynamics, an emblem of the rapid increase in inequality, have led to a stratification of classes and groups in a regime of substantial coexistence which has amplified the perception of the marginalisation of the poorer segments of the population, especially the young who are trapped between the dream of riches and the disenchantment of deprivation, often co-opted by criminality. In a country where youth unemployment is almost 40%, the young people frequently face a lack of education and training, despite the government having started various initiatives within the Youth Enterprise Development Fund, Vision 2030 and the former Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation.

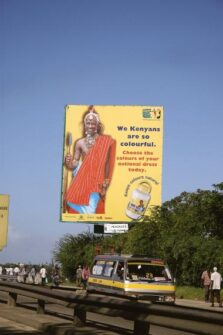

The vitality and complexity of Nairobi is also shown by the vibrant music scene which is going beyond the confines of Kenya, especially regarding hip hop and electronic music, with productions by artists like The Cosmic Homies, Khaligraph Jones, Karun and Octopizzo. The parabola of Nairobi hip hop has its roots in the slums, in contexts of social conflict and contestation, poverty, violence and discomfort. The song ‘Wajinga Nyinyi’ by King Kaka, for example, is one of the soundtracks of youth protests against corruption, misgovernment and the feeling of being deprived of a future. The former group Ukoo Flani has made the suburb of Dandora, the site of the largest dump of the city and the centre of dubious business between Italy and Kenya, into one of the main rap scenes of the country. All this is accompanied by the coloured graffiti culture which, in defiance of the law, is to be seen on the matatu, the privately-owned minibus taxis. In the midst of such a scenario, not many people would connect the concept of a ‘smart city’ with a metropolis like that of Nairobi. Yet, an experiment is taking place to use technology to modernise the city and render it more visible, also helping it to face the dangers posed by climate change.

The terms and conditions are dictated by a society where the average person is young, where new technologies are slowly but inexorably taking hold thanks to the development of telecommunications and digital technology in the field of banking and finance. It is no coincidence that the project ‘Konza City’ was born in Nairobi. This involves the idea of creating a sort of Kenyan-style Silicon Valley, a project worth 14.5 billion to be built 60 kilometres from the city that could create about 20,000 jobs. It is planned to function as a real smart city capable of collecting data on traffic, transport, energy, and construction. Like the Konza Technopolis, a hub of innovation and research which, though rather late in comparison with others, is proceeding by leaps and bounds.

These are small signs of hope in a difficult context, forging ahead and making up for lost time. Perhaps they are but a drop in the ocean, but they may help Nairobi to quench its thirst for a future.

Luca Cinciripini – Beniamino Franceschini/CgP