Iraq. Lalish, the Sacred Heart of the Yazidis.

Persecuted and driven from their homeland, Sinjar, in Iraqi Kurdistan, Yazidis cling to their religion and traditions such as the pilgrimage to the most important shrine. We visited the place.

“Angels live on the threshold of every entrance, so it is important not to step on the entrance steps”. This is one of the rules that visitors and pilgrims hear repeated upon their arrival in Lalish, the valley in northern Iraq where stands the mausoleum dedicated to Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir, who died in 1162 and is venerated here as a saint, together with his successor Sheikh Hasan.

There are just a few rules to be followed: you walk barefoot and do not disturb the angels. We are ready to visit the shrine, a sacred place for the Yazidis, a religious minority originally from Kurdistan, a region that includes parts of Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran. Today they are also found in Armenia, Georgia, Russia, and Europe and it is estimated that there are about 700 thousand in all.

Lalish is located in Duhok Governorate in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Levi Clacy

The sanctuary of Lalish is located 35 kilometers north of Mosul. Even from some distance you can see the large conical roofs of the tombs typical of the Yazidi culture. The same structure, symbolizing the sun at the top, the rays along the surface of the cone and the earth at the base, is found in villages where a sheikh, a local religious guide belonging to the highest caste of the community, died.

But the Yazidi tenements in Iraq are recognizable above all by the entrance gates adorned with the image of a peacock, in honor of Melek Taus, the most important angel. According to tradition, when God created the world, he entrusted its protection to seven angels, including Melek Taus, the peacock angel. To test them, God asked them to bow before Adam, the first man. Only Melek Taus refused and was rejected by all mankind, with the exception of the Yazidis.

The same scene is described in the Qur’an, with the difference that the angel in question is Iblis (Lucifer in Christian tradition). God commanded Iblis to prostrate himself before man, but he refused and was cast out of Paradise. This is why the Yazidis have been persecuted for centuries and defined by Muslims as ‘devil worshippers’.

In reality, Melek Taus is not an evil figure; on the contrary, he is the leader of the archangels who decided to swear obedience only to God and no one else. According to other sources, the Yazidi religion originated in Iran, after absorbing the influences of Zoroastrianism and the Yazidis would have taken their name from the city of Yazid. Ancient Persian beliefs tell how Ahriman, the Evil One, created the peacock to prove that he too, like God, was able to give life to beautiful creatures.

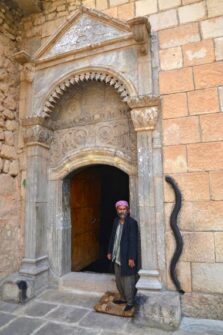

An important spiritual representative of the Yazid religion in Lalish, sits by the wall at the entrance to the shrine with the tomb in Lalish. 123rf.com

More recent research indicates that the religion began in the twelfth century with the preaching of Sheikh Adi, who had created a Sufi brotherhood called Adawiyya. Coming from Lebanon, Sheikh Adi settled in Lalish to lead an ascetic life. The Yazidis venerate him as a saint because they believe he is an emanation of Melek Taus, but the mausoleum of Lalish dedicated to him was, according to some, originally a Nestorian church.

Whatever the origin of the Yazidi creed may be, which combines the millennial traditions of the Mesopotamian plain, its adepts have been persecuted for centuries because they are considered worshippers of Satan. Endogamy and the prohibition of revealing their precepts, handed down mostly orally, have only fuelled the mistrust of Christians and Muslims.

Although there is some sort of baptism among Yazidi ceremonies, one cannot become a Yazidi. It is necessary to be born in the community and it is mandatory to marry within it, under penalty of ‘excommunication’. Yazidism is in fact based more on a series of rules than on prayers and rites. It is said that the teachings of Sheikh Adi were contained in what is called the ‘Black Book’, which was lost a thousand years ago, but its very existence is doubtful.

Prayers are personal and always said turning towards the sun.

There are three castes: the sheikhs, the priests, which include about 30% of the population, followed by the pir and the murad. The most important religious office is held by Baba Shaykh, the ‘Pope’ of the Yazidis, whose appointment is hereditary but must be approved by the other senior sages. The difference between the various castes lies in the way religion is practised: only the sheikhs, for example, are required to fast for forty days in winter and then again in summer, while everyone else should make at least four trips a year to Lalish on the occasion

of the main holidays.

At the entrance to the temple, you are greeted by a guardian. 123rf.com

At the entrance to the temple you are greeted by a guardian who, in front of a steaming cup of çay (the abundantly sweetened tea as the Middle Eastern tradition dictates), explains the rules to visitors. Taking some soil and placing it in a white handkerchief, he creates a sort of amulet that protects pilgrims and that Yazidis usually keep in their cars. Men dressed in traditional Kurdish clothes and women with the characteristic lilac veil kiss the door jambs and leave money on the thresholds to secure the favour of the guardian angels.

Crossing a series of courtyards you arrive at the tomb of Sheikh Adi, wrapped in fabrics of different colours. Pilgrims who want to make a wish must first untie a knot previously made by another pilgrim (and they will see their dream come true) and then tie a knot on part of the cloth themselves. Corresponding to the main rooms, there are two water springs, of which the most important is called Zemzem (of the same name as the well that is located in Mecca) and to which access is forbidden to non-Yazidis.

The springs are the holiest place in the temple because water is believed to have magical and healing properties, according to some because Lalish rises on a geomagnetic point of the Earth.

At sunset to light a series of lamps that are placed in various rooms of the temple. CC BY-SA 4.0/ Levi Clacy

There are also lodgings, kitchens, a room full of bread for pilgrims and an underground room that contains skins full of oil, used every day at sunset to light a series of lamps that are placed in various rooms of the temple. In this room, once unadorned, in recent years the handprints of visitors have appeared on the rock walls: “I had never seen them before,” our guide told us, revealing that the Yazidi religion, based on oral tradition, has no problem ‘inventing’ new rites from time to time.

A mural depicting a scene from the universal flood explains the importance of the black snake, revered by the Yazidis, but considered malignant by other monotheistic religions. Traditionally, when Noah’s ark was sinking, the serpent saved the patriarch by closing the hole with his own body. The door of the temple that leads to the sacred springs is also flanked by a black snake carved in stone.

Foreign visitors are welcome in Lalish. One almost has the impression that after the persecutions of recent years, the Yazidis feel the need to make themselves known in the eyes of the world because they fear they may disappear forever. There are no official figures, but it is estimated that the faithful remaining in Iraq number between 300 and 400 thousand. In Germany alone, there are 200,000 Yazidi immigrants and we often hear German spoken in Lalish, along with Kurmanji, one of the Kurdish dialects.

Yazidi men. CC BY-SA 3.0/ Bestoun94

The community made headlines in 2014 due to the persecution of ISIS. The girls who were kidnapped, raped and often become pregnant, were rejected by the community of origin even after the expulsion of the Islamic State from Iraq in 2017, because they had had relations with enemies. Between two and three thousand women took refuge in Germany, even though the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had built houses for them along the road leading to the sanctuary, hoping to facilitate their reintegration. The apartments are still uninhabited; the stigma has been stronger than the desire to welcome them back into the community.

Yazidis are still under threat today: under the pretext of eliminating members of the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) considered ‘terrorists’ by Ankara, Turkish drones, with the complicity of the Baghdad government, continue to hit Sinjar, the region in northern Iraqi Kurdistan, forcing thousands of civilians to flee.

In fact, the Yazidi Resistance Units, formed in 2014 to fight against ISIS, and which now collaborate with the PKK to obtain an autonomous Kurdish region, operate here. Meanwhile, however, in Iraqi Kurdistan there are still about 200 thousand displaced Yazidis. ‘We would like to go home’, the young people we met in the Bajet Kandala refugee camp, on the border with Turkey and Syria, told us. ‘Sinjar is the homeland of the Yazidis, but for us there is still no peace’. (Open Photo: Lalish, an important holy site of the Yazids. 123rf.com)

Alessandra De Poli/MM