Ghana. ‘Dipo’ Puberty Rites: Transitioning into Womanhood.

The Dipo rite is an integral part of the Krobo culture. Over the years it has been used to inculcate useful values into adolescent girls as they prepare to assume their marital responsibilities.

The Krobos are part of the Ga-Dangbe ethno linguistic group and they are the largest group of the seven Dangbe ethnic groups of South-Eastern Ghana. Dipo is a historical rite of passage for young females transitioning into womanhood among the Krobo people

in the Eastern Region of Ghana.

Dipo is not unique to the Krobos alone, but it is celebrated by the people of Manya and Yilo Krobo, in Krobo Odumase and Somanya.

The inhabitants of Odumase Krobo area therefore celebrate the Dipo as an annual ritual intended to launch puberty-aged girls and virgins into womanhood. The ritual, which is traditionally performed on a young girl, denotes that she has matured into a woman and is ready to marry.

The ritual which is usually marked as festival is held in the month of April every year, a time where parents send their qualified girl children to the town’s top priest after the event is announced.

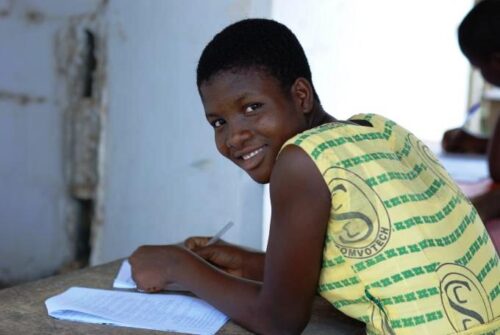

The goal of Dipo is to assist pubertal girls in transitioning into adulthood by shaping moral values and social responsibilities. File swm

Parents upon hearing the Dipo initiation dates send their adolescent girls to the chief priest under whose tutelage the girls would have to go through various tests and rituals to prove that they are qualified

for the Dipo rites.

The qualified initiates are then adorned with a bead-necklace and strand of leaves. Little cuts are also made on the arms and one by one they lift up a small grinding stone and place it on larger stone. Their introduction to the grinding stone marks the beginning of the Dipo rite. They are kept for a while till they are sent to another part of the mountain ‘Tegbe te’ or ‘Tegbe rock’ and given Dipo- headwear, a tall straw hat.

These young girls are subsequently put through a series of procedures to verify their chastity and eligibility for the rites, which are exclusively open to virgins and girls in puberty.

The goal of Dipo is therefore to assist pubertal girls in transitioning into adulthood by shaping moral values and social responsibilities, learning home management skills, and preventing risky sexual behaviours.

One theory has it that Dipo was introduced by the priestess of Krobo land, Nana Kloweki. Historically, Dipo was instituted to mark the stage of puberty and was intended for young females of marriageable age, although it is now performed with girls younger than puberty.

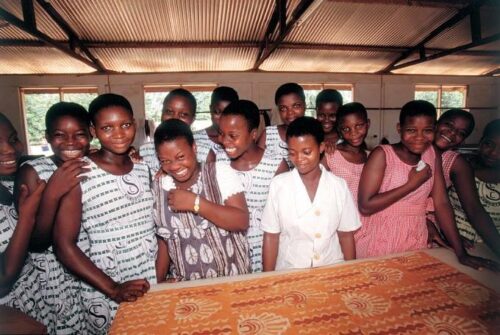

During the rites, Krobo participants acquire skills to fulfil roles as responsible female adults, including vocational training, house-keeping skills, and preparation for married life.’

During the rites, participants acquire skills to fulfil roles as responsible female adults. File swm

The significance and symbolic nature of ‘Dipo’ is enormous and intriguing including the propagation of a lineage, status, and family organisation. Others believed that Dipo was a traditional method of preventing promiscuity, infidelity, premarital sex, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted infections.

Dipo involves several symbolic actions. Exposure of a person’s body, such as the breast and stomach, is used to distinguish initiates from non-initiates, and help identify those ready for marriage, and detect pregnancy.Libation is poured at the beginning of most rites to ask the ‘gods’ to bless all Dipo participants. Blood of castrated goats, which is usually poured on initiates’ feet, is believed to wash away bad omens. This is also to drive away any spirit of barrenness.

Different types of beads used during Dipo rites have specific names and meanings. Those with many types of beads signify wealth. Blue beads are called ‘Koli’, meaning something valuable. Yellow beads represent maturity and prosperity, whereas large yellow beads are known as ‘Boredom’ and are believed to possess magical powers. White beads signify respect for gods and ancestors. Finally, while not compulsory, an incision may be done as a form of identity on the back of the left hand for those who have successfully completed Dipo rites.

There are stages where a Dipo rite of passage can be classified based on specific activities. The first stage, known as the stripping stage, involves replacing everyday home attire with a string of multiple beads and dressed with cloth around their waist to just their knee level. Dipo participants also have their heads shaved during this period.

This is done by a special ritual mother, and it signifies their transition from childhood to adulthood. They are paraded to the entire community as the initiates (‘dipo-yo’- Dipo girl).

The second and third stages (middle and climax, respectively) emphasise different symbolic activities, including having a special meal (fufu), taking a ritual bath, and smearing the body with a white substance.

The girls who go through the rites receive a mark on their hands as a sign of participation. File swm

The climax phase involves the pouring of libation (three consecutive times) and climbing a sacred stone. The final stage consists of activities that include body marks and the last dance. Dipo includes other rituals such as eating particular types of meals. Dipo initiates learn a special dance known as ‘Klama’, where the dead and the living are believed to participate. Participants usually undergo a ritual bath and are required to sit on a stone before the ceremony ends to determine their virginity in the past. This is to prove their virginity. However, any girl found to be pregnant or not a virgin is detested by the community and does not entice a man from the tribe.

No girl who has sat on the stone has seen what it looks like as they are made to close their eyes. As soon as the girls step out of the stone enclosure, parents run as a sign of victory to carry their daughters, and rush out of the area. The stone serves as a stool for kings in the olden days because there were no proper stools. The forefathers brought the stone with them during their migration to their present place.

As traditions demand, when the girls sit on the stone, they receive blessings from their ancestors. And therefore become ‘oheneba’ (the daughter of a king).

Adolescent girls who did not go through the rites could neither be queen mothers nor serve the community while girls who went through the rites received a mark on their hands as a sign of participation.

Following all of this, the young girls are sheltered for a week and taught about femininity, marriage, and the people’s customs and traditions. The children are then returned to their parents. The Dipo ceremony culminates in a large durbar in the community, during which the girls are dressed in Kente (specially woven cloth) and given exquisite jewels by their parents. Any male present at the durbar who is interested in one of the girls might start looking into her past and family at this time before making an official approach.

Dipo involves several symbolic actions. File swm

With singing and drumming, they perform the Klama dance. At this point, any man interested in any one of them can start investigating into her family. It is believed that any lady who partakes in the rites not only brings honour to herself but to her family at large.

In as much as the Krobo people practice Dipo, not all Ghanaian or even the Krobo people accept Dipo rites, and there have been disagreements about its value and actual essence. While some people believe it is a cultural practice that should be continued, others believe it has no significance in modern Ghanaian society. Because Dipo is conducted within traditional African religion and culture, Ghanaians influenced by Western culture and Christianity may believe it to be unacceptable. Another aspect of the debate is the initiates exposing certain parts of their bodies to the public to signal Krobo men of their readiness for marriage. Today in some communities, Dipo initiates are allowed to cover their breasts with a ‘wax-print cloth’. This change was made to cater for current societal opposition of exposure of private body parts.

Finally, Christians may view Dipo rites as a practice that is traditional and unacceptable to Christian beliefs. For example, Dipo rites include practices, such as ancestral worship, incisions, and ritual baths, practices opposing to Christianity. Many communities in Ghana today do not have rites of passage. However, traditional leadership and customary law among some ethnic groups have retained the cultural legitimacy of rites of passage, such as in the Krobo community.

Damian Dieu Donne Avevor