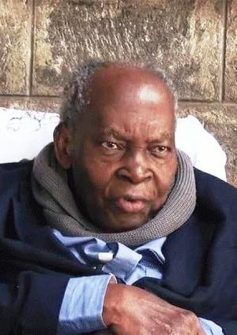

Father Charles Nyamiti. “An ancestor in African Theology.”

The Tanzanian-born priest, Fr. Charles Nyamiti, will be remember as eminent pioneer of African Theology “brewed in an African pot.”

In the strict sense of the concept, “African Theology” as a theological genre within the Christian churches (and, in the specific case of this article, within the Catholic Church), is barely 60 years old. The notion began to be boldly proposed and openly claimed only in the decades of the 1940s and 1950s. It was understood to denote a distinctive way of thinking about and articulating the Christian faith tradition by taking seriously into account African spirituality, culture and religion. By this was meant the comprehensive way of understanding the world and their place in it by the black peoples of the African continent.

Two texts published during these decades were seminal in the rise and development of African Theology in the evident scientific sense. One was the book named La philosophie bantoue or “Bantu Philosophy” by the Belgian Franciscan missionary in the Congo, Placide Frans Tempels. It was first published in 1945. The other was called Des prêtres noirs s’interrogent or “Black Priests Wonder.” This was a compilation of articles from a consultation of a group of African priests studying in France at the time. It published in 1956. Each in its own way, these books raised consciousness within the church and beyond about the necessity and urgent need of thinking about and living religion “in an African way.”

To the question, who is the most outstanding symbol of such academic African Theology today, the answer is very easy. Any serious student of theology in Africa will come up with two names in a blink of an eye, especially where the English speaking region of Africa is concerned. Besides the Kenyan Anglican Canon, Prof. John S. Mbiti (Nov. 30, 1931-Oct. 6, 2019), the other name to be quickly mentioned will be that of the Catholic priest, Prof. Charles Nyamiti (Dec. 9, 1931-May 19, 2020). Whereas Mbiti specialized particularly in the field of African religious philosophy, Nyamiti worked in the area of theology proper. Without any doubt, these two have been the leading and enduring voices in the African theological field.

Charles Nyamiti passed on in mid-May this year (2020) after serving as a professor of theology for many years – since 1984, to be exact – at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Nairobi, Kenya. Nyamiti was one of the founder-lecturers at that Establishment. It was then known as the Catholic Higher Institute of Eastern Africa (CHIEA). Previous to that, he had lectured at the St. Paul national major seminary at Kipalapala on the outskirts of Tabora town in the north-western parts of Tanzania.

He was assigned there in 1976, shortly after completing graduate studies in Theology, Social Anthropology (or Ethnology) and music composition at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and in Vienna in Austria, respectively.

Young Nyamiti’s theological studies in Belgium were pretty standard in Catholic perspectives at the time, heavily tinged with European ethno-centric biases in terms of expressing the Christian faith. But he had already then manifested a remarkable interest in employing African symbols in expressing the Christian faith.

Some people explain this away as merely coincidental, but it seems to many of us much more accurate to interpret this in terms of divine providence that guided him to orient his studies towards an Afro-centric emphasis despite the dominant European academic environment at the time. As illustrations, we may refer to both his Master’s and Doctoral theses to show this inner inclination.

For both degrees Nyamiti concentrated on the processes and meanings of the rites and rituals of initiation to adulthood as practiced in some African ethnic communities in view of the understanding of corresponding sacraments in the Catholic Church. He intended to show that despite the differences of approach between them, African indigenous and Western Christian approaches to these rituals, they were matching in terms of the meaning and intention at their core.

To say this may not be shocking today, but in 1966 and 1969 when Nyamiti wrote and defended these ideas, they were intellectually and doctrinally revolutionary, if not heretical, to say the least, even if Vatican II had just concluded.

It was this zeal for creating a “mature, adult and dignified way of conceiving, perceiving and talking” about the Christian faith in the African milieu that formed Nyamiti’s theological preoccupation throughout. Again it involved the issue of how to express Christian mysteries without in the least adulterating the sense of Christian belief. In summing up Nyamiti’s lifetime work, we can indeed distinguish in it between what one of his students, Prof. Mika Vähäkangas characterizes as Christianity served in “foreign vessels” and what another African theologian, A. E. Orobator, describes a theology “brewed in an African pot.” Nyamiti has worked tirelessly for the latter.

African theologians would agree with Vähäkangas that “There are few … [people] who have dared to venture as far as Nyamiti … in constructing a complete African theology covering the whole field of dogmatics.”

In a field now quite replete with individual theologians and theological associations in one way or another interested in the field, this is no mean compliment. In doing what Nyamiti has done, I claim that Nyamiti has lifted African culture to a status that is “equally capable and worthy as any other to be a receptacle of Christic values in the African context.” Here we have Nyamiti’s greatest bequest to African and, indeed, world Christianity. Nyamiti’s has been a struggle to unearth values deeply embedded in African beliefs and behavior that, in the words of Joseph T. Djabare, “can unlock the African soul and open it for an authentic

union with Christ.”

Pope Paul VI already affirmed this in his Message to Africa in 1967, saying that “Many [African] customs and rites, once considered to be strange, are seen today … [to be] worthy of study and commanding respect.” These include, in the Pope’s mind, the Africans’ “spiritual view of life,” their “idea of God,” “respect for human dignity,” “the sense of family” and “community life.” All of these the Pope viewed as “providential” insights. It is to these that Nyamiti in his theological method has sought to offer Christian expression.

Collaborating this intuition and goal, Pope Francis writes in his recent Apostolic Exhortation “The Joy of the Gospel” (Evangelii Gaudium), reminding the universal Church about why “We cannot demand that peoples of every continent, in expressing their Christian faith, imitate modes of expression which European nations developed at a particular moment of their history, because the faith cannot be constricted to the limits of understanding and expression of any one culture. It is an indisputable fact that no single culture can exhaust the mystery of our redemption in Christ.” The core of Nyamiti’s work captures this truth.

One outstanding contribution by Nyamiti to theological discourse in Africa that will be remembered above all is in the area of Christology. Who is Jesus for Africa? Who is Jesus for Africans in their cultural milieu? Early on in his reflections, Nyamiti proposed the image of “Ancestor” to depict the identity, mission and ministry of Jesus as one that the majority of African peoples could easily understand and relate to. His African Ancestral Christology has been lauded throughout the continent as a theological breakthrough.

Nyamiti’s seminal publication in this area, titled Christ as Our Ancestor: Christology from an African Perspective, is identified as “monumental” by one of his former student, Dr. Patrick N. Wachege.

In his many of his writings, Nyamiti constantly returns to this theme as central as well in terms of appreciating the mission and ministry of the Church in Africa. In view of the values rooted in the African worldview, as was explained previously, Jesus is the Ancestor par excellence in the “Family called Church” or in “the Church as Family.” Canadian Africanist scholar Diane B. Stinton explains why, on account of the indisputable “vital” role ancestors play in African life, the vast majority of African theologians “lend various degrees of assent and priority” to this image of Jesus Christ as Our Ancestor.

On this issue, Nyamiti is not merely theoretical. He puts it quite clearly that the “most decisive step” in the development of African (Ancestral) Christology will only come when it is “allowed to enter into the magisterial teaching of the Church.” His call to African theologians and the African Church at large is that the goal of Christological thinking in the African continent should be to enable this perception of Jesus Christ “to influence, as far as possible, the doctrinal formulations of African bishops’ conferences and synods.”

Even during his earthly life, Nyamiti was popularly known and referred to by his students as “Ancestor” on account of his wisdom. Now that he has gone to join the Ancestors in reality, the African Church must remember what an African saying reminds us all, that “To forget one’s ancestors is to be a brook without a source, a tree without roots.” It is a grave responsibility we owe to this illustrious giant of African Theology, Charles Nyamiti. The African Church remains ever grateful to God for the life and theological thought of Charles Nyamiti.

Laurenti Magesa