Ethiopia. Meskel. The Feast of the Holy Cross.

There is no feast in Ethiopia, religious or civil, so popular and with such large social and family roots. What is celebrated

on the day of Meskel?

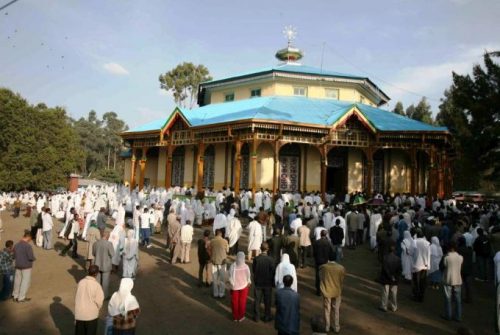

The New Year begins in Ethiopia on September 12. That date should be the starting point for the activities of the school year. But, although it is officially so, nothing gets under way completely until the celebration of Meskel, or Santa Cruz, which takes place on September 27. Students may go to school, but they will find that half of the teachers are missing. Or the teachers can start their classes, but half of the students will be missing. In some regions of Ethiopia, like Guraghe, it is almost mandatory that all the dispersed have to return to their father’s house to celebrate the Meskel. There is no feast in Ethiopia, religious or civil, so popular and with such large social and family roots, certainly more than Christmas or Easter.

What is celebrated on the day of Meskel? Throughout the Christian world, at least the Catholic and Orthodox, the so-called Discovery of the Holy Cross is celebrated, which commemorates the discovery of the true cross of Jesus by St. Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine, in the first half of IV century. Each Church has developed its own traditions around the event of the discovery and about the whereabouts of the cross. The most common and widespread claim is that, while excavating, Santa Elena found three crosses buried in a site not far from what was supposed to be the crucifixion place. To know which of the three was that of Jesus, they put one by one on a sick person. It was the third one that cured him and they assumed that was the true one. They divided it into pieces, which they sent to the main churches of the Christian world. One of those pieces went to Alexandria in Egypt.

And there’s where the specific Ethiopian tradition starts and where the deep veneration of the Holy Cross is rooted. It is said in this tradition that the Christians of Egypt were continually persecuted by the Muslim rulers. At a time of greater oppression, in the fourteenth century, the Egyptian Church asked for help from the Ethiopian emperor, who at the time was Dawit II. He threatened the Egyptian authorities with cutting off the waters of the Nile and reducing them to starvation. Frightened, Muslims ceased persecution. Here the versions are diversified. According to one, it was the Muslim authorities themselves who, to appease the Ethiopian king, sent to Ethiopia a part of the piece of the Holy Cross preserved in the patriarchal see of Alexandria. According to the other version, on the other hand, it was the Patriarch himself who sent the piece of the cross in thanksgiving for the effective intervention. There is still another version, quite different from the previous ones, which states that the piece of the true cross was sent to Ethiopia by the ‘King of the Franks’ in the time of Emperor Zera Yakob (1434-1467) and that it was contained in a gold box, which was, in turn, inside a larger box, also of gold, in the shape of a cross.

For complex circumstances, the cross went to a mountain with a flat summit that somehow resembles a cross. It is called Gishen Mariam, in the northern province of Wollo and there it has been venerated over the centuries to the present. Hundreds of buses go every year from Addis Ababa and from other parts of the nation carrying faithful for the day of the festival. It is custom throughout the nation to have the ‘demera’ burning on the eve of the feast. It consists of burning a pile of firewood, previously arranged. That of Addis Ababa is especially spectacular, held in the square called Meskel, which is attended by the highest authorities and civilians of the capital. Although performed in the midst of religious songs and blessings, the connections of the ‘demera’ with the liturgical feast of the cross are not clear and seem rather a reminiscence of an ancient pagan celebration.

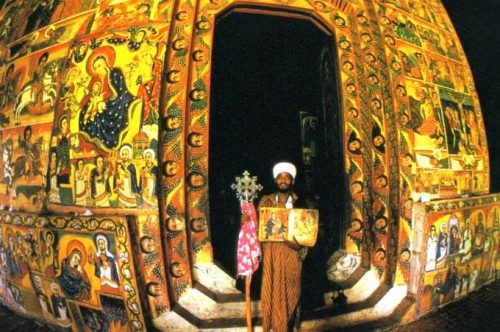

Whatever the strictly historical value of all these traditions, the unquestionable fact is that the veneration of the holy cross is one of the most salient features of Ethiopian spirituality. That devotion has one of its expressions in the profusion of crosses in all places, of all possible shapes and sizes. There are crosses in the church domes; crosses called processional, because they are placed on the top of a mast and serve to preside over processions; hand crosses carried by priests in their hands and given to the faithful to kiss whenever they come to greet them; small crosses hanging from their necks; crosses marked with indelible ink on their foreheads or on the backs of their hands. It is said that it was the emperor Zara Yakob who imposed the practice of this tattoo, so that Christians were distinguished from Muslims.

Despite the variety of forms, there are some characteristics common to all. The first is that it is exclusively the cross without the figure crucified on it. The reason is that the Ethiopians see the cross as a sign of victory, hence the suffering Christ passes into the background and is not represented. The second is that, in their foliage, the crosses resemble a tree. And here too, the theological motivation is clear: it refers to the tree of life spoken of in Genesis, which was only a pre-announcement, because the true tree of life is the cross on which Jesus died.

Juan González Núñez