Egypt. Pigeons, what a passion.

In the shade of the pyramids and minarets of Cairo, the tradition of pigeon and homing pigeon breeders has been handed down.

Cairo is a chaotic, immense and difficult city. The streets are always too crowded and the continuous cacophony of horns denies concentration and quickly exhausts one’s energy. But raise your eyes and you will realize that there is another level of the city, hidden and almost inaccessible, a kingdom where birds and their keepers are masters.

It’s a day like many others in the working-class heart of Cairo; the streets crowded with vendors and three-wheeled vans all look the same, dominated by the tall concrete and red brick buildings that have sprouted like mushrooms in recent decades. A monotony of shapes and colours broken only by a large flamboyant structure similar to a cistern or a crooked medieval tower that seems to be supported with long, unstable stilts on the flat roof of a building.

A boy with pigeons at the Souk al Gomaa Friday market in Cairo. Shutterstock/Emily Marie Wilson

Groups of people crowd around the wooden pillars and along the dizzying ladder that seems liable to collapse at any moment. Suddenly, one of these figures takes out two large red flags and starts waving them with regular and rhythmic movements while keeping his eyes raised to the sky. Soon a flock of birds begins to circle lower and lower towards the roof of the building.

It is one of the thousands of gheyas that dot the roofs of the Egyptian capital: dovecotes where many Cairo residents can dedicate themselves to pigeon breeding, a widespread passion which for some is also an important source of income.

Ancient Roots

According to historians, the Egyptians’ love for pigeons is so ancient that even hieroglyphs testify to their widespread presence and the custom of offering them as sacrifices on the occasion of rites or funerals, while in the era of the Fatimid rulers (X-XII century AD) the use of birds as messengers and pets is documented.

It is a tradition found not only in the cities but also in the countryside: in the villages of the delta or further south along the river, and in the enormous agricultural area of the Fayyum, it is not uncommon to notice flocks of birds crowding around certain high constructions.

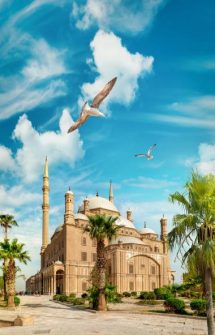

Muhammad Ali Mosque in Cairo. 123rf

Rural dovecotes are large conical towers similar to chimneys made of sun-dried mud, where holes arranged in geometric patterns and transversal wooden poles allow the pigeons to rest or enter, sheltered from predators.At first glance, their appearance recalls the shape of the minarets of Sahelian mosques and the unmistakable outlines of the rural landscapes that wind along the Nile.

And food has nothing to do with it: while it is true that these birds are often found in various typical delicacies such as the famous hamam mahshi, pigeons stuffed with spiced rice and bulgur cooked for a long time in the oven, at the same time, bird breeding is a true passion that has been handed down for generations. Pigeon racing, for example, is a widely practised sport: on the rooftops of Cairo, many both young and old spend entire afternoons training their squadrons with large flags acting as a call to the roost.

Heavenly challenges

The most common type of race is the long-distance speed race. This involves the flocks being released in distant cities with an encrypted message, contained in a package attached to the leg, which is communicated by the farmers to the jury as counter-evidence as soon as the birds reach the base. These can be seen as Marathons of the skies that fascinate and become legendary competitions, like the one that takes place annually between Cairo and Aswan, almost 700 kilometres of flight across the whole of Egypt.Besides racing, there are other hobbies involving pigeons. Other very popular competitions involve real wars between flocks that have to capture or try to free themselves from opposing teams, with the ownership of the birds themselves and the consequent size of their “army” at stake.

An old woman selling pigeons in an Egyptian market. Shutterstock/RovingPhotogZA

Once down from their towers, breeders and enthusiasts have an unmissable meeting point: the animal market held on Fridays around Al Khelaa, the long road that crosses the famous suburb of the “City of the Dead”. Along the road, thousands of coloured plastic cages are piled up from which birds of all types look out, from tiny canaries to enormous hawks motionless on their perches.

Pigeons and doves are obviously among the best-sellers here. To the untrained eye, these immense flocks are distinguished only by their plumage, which ranges from pure white to dark grey and beige, but the attentive gaze of the breeders can immediately identify different species with their respective characteristics and qualities, establishing the setting of prices starting from a few tens of Egyptian pounds for the youngest and most inexperienced specimens and reach several thousand, more than the average monthly salary of an Egyptian.

Architecture to be conserved

In addition to its social, cultural, economic and ecosystem enhancement aspects, the tradition of pigeon breeding also has its effects on the urban landscape and the appearance of the city. In fact, the gheya are unmistakable structures that make the roofs of Cairo unique. A dizzying castle of vertical and diagonal wooden poles up to 7-8 meters high on which rests a large fence made of thin wooden slats placed side by side and painted in bright colours and with geometric decorative motifs.

Inside the enclosure, accessible with ladders, cages are arranged along the perimeter, while a wide rope net acts as a ceiling and prevents the possible arrival of predators or rival flocks.

Pigeons in Giza City flying on the houses. 123rf

Like tall and lively medieval watchtowers, the pigeon lofts overlook the entire city, becoming a distinctive architectural element, especially in the working-class neighbourhoods where the monotony of the buildings with a concrete skeleton and red brick walls interrupted by a few sparse windows is enlivened by the colours of the decorated walls.

In its frenetic growth, the Egyptian capital (one of the largest metropolises on the planet) is inexorably destroying fundamental parts of its past, such as the famous awamat, the centuries-old floating houses removed from the banks of the Nile a year ago, or various inhabited tombs of the City of the Dead, demolished to widen highways and bridges.The most popular areas are especially prone to suffer demolitions and heavy transformations daily in the name of mobility, urban decorum and a questionable idea of progress that has no regard for anyone, not even for history. The pigeon lofts, however, seem to resist, perhaps thanks to their elevated and almost hidden position, and continue to give colour, lightness and vitality to the skies of a difficult city which never ceases to surprise. (Open Photo: Sunset over Cairo with silhouettes of flying birds. Shutterstock/Repina Valeriya)

Federico Monica/Africa