Dubai. The crossroads of African gold.

An interwoven series of criminal gangs, terrorist groups, traffickers of all sorts, networks of illegal commerce, African gold passes through the Emirates.

Gold represents the best investment during great economic and financial crises. The past fifteen years have been characterised by a dizzying climb in the price of this product which has given rise to the creation of several ‘artisan mines’ in the countries of eastern and central Africa.

Such enterprises, in unstable or conflict zones as in the case of Africa, represent a greedy segment that must be divided up and controlled, of criminal gangs, terrorist groups, traffickers of all sorts and networks of illegal trading. The business is even more greedy when there is a large amount to be extracted as is the case in the areas in question where the value of the gold extracted is around $3billion a year.

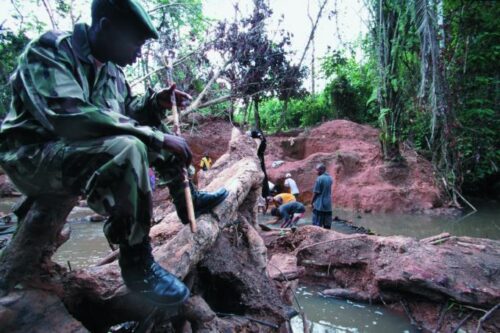

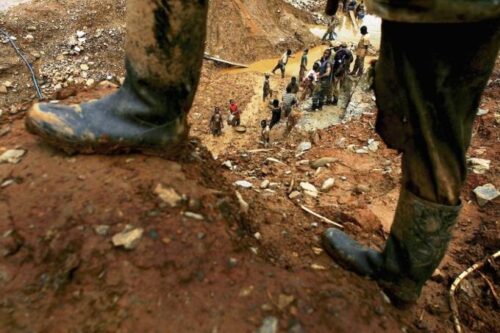

The ore produced represents a considerable source of revenue for the estimated 19 million workers of the artisan mines and the communities to which they belong. Although the work is very heavy, done with no protection whatever and involving women and children – the children, being physically small, are able to crawl into the narrow tunnels – the workers receive but a tiny part of the earnings.

Research carried out by The Sentry, a US organisation that aims at unmasking the economic sources that foment and support armed conflicts, examined the four countries richest in gold reserves – Sudan, South Sudan, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo – whose common characteristic is that they have been the scene of decades-long conflicts.

It has emerged from this study that, within this chaotic universe, the criminal groups are free to control the supply lines by taking the place of legal intermediaries, due also to connections with foreign companies looking for easy earnings which, by using qualified traders, succeed in obscuring their ties with armed groups and bring the gold to the legal market. In more detail, it is apparent that in eastern Congo, where each year 10 to 20 tons of gold are mined, thanks to the work of about 250 miners employed in the sector, about 70% of the mines is controlled by smugglers and armed groups. The situation in the Central African Republic is not dissimilar where 27 armed groups control the smuggling of 90% of the annual production which recently showed a significant increase, reaching 5.7 tons per year, worth around $235 million.

Then there is Sudan which, with its production of 90 tons of gold per year, makes it the third-largest producer in the world, where production is on an industrial scale with only a minimal presence of artisanal mines. Despite this, the rules in force are the same as those in other producer countries since a good proportion of production is managed by the Sudan Liberation Army -Abdul Wahid – and by the Movement of Liberation of the north of the Sudanese people which, with funds generated by the artisanal mines, finance their activities.

In South Sudan, activity is in the hands of the two main armed groups, the Movement for the Liberation of the People of Sudan/Army of opposition and the National Salvation Front. The gold produced by these territories ends up on the global market: in the United States, Europe, Asia and the Middle East. However, before reaching it, 95% of production passes through Dubai where it is mixed with other gold from the legal market so as to eliminate any traces of its origin and then place it ‘legally’ on the international market. This practice is facilitated by weak legislation in the UAE concerning the subject and poor inspection practices regarding the origin and certificates of purchase of the mineral, as well as the possibility of making the transactions in cash or by exchange. These factors are decisive for the large international intermediaries which are devoid of scruples and make Dubai the main sorting-house for illegally produced gold. Gold is, for the economy of the Emirates, a strategic asset and exports in 2019 were valued at $19billion, not far behind the petroleum companies.

From Dubai, the gold is taken to India, China, Switzerland and the Middle East, in what is in essence a process of recycling, for which other countries, especially Switzerland, must certainly bear no less responsibility. Switzerland, in fact, gives fundamental support to this strategy of triangulation with other destinations. There, the gold coming from Dubai undergoes further refinement and then goes to the United Kingdom, making it a world-level importer.

Returning to the start of the journey, it is observable that, as indicated by a study led by the Director of Africa Confidential Patrick Smith, that from Bukavu in South Kivu, 300 kg of gold pass every month towards the Gulf, while officially only 5 kg are declared. According to Mario Giro, the former Italian vice-foreign minister, the refineries present in the area of the Great lakes produce as much as 330 tons and one of the largest refining companies is the Ugandan ‘African Gold Refinery’, capable of refining 219 tons per year, and the Rwandan ‘Aldango’. Both have in common the fact that they are the bases for a Belgian company whose sales office is located in Dubai.

The Sentry report also shows export data together with those of imports and, here too, the emerging anomalies clearly show that the Emirates declared they import from the African countries a quantity of gold superior to what those countries declare they have exported.

In this regard, significant cases are those of Sudan which declares that it exported, from 2010-2014, 152 tons of gold to Dubai which received, during the same period, 248; that of Uganda which declares it produces 3 tons of gold per year while declaring that it exports around 9 tons to the UAE; of Rwanda with official production of between 0.03 and 0.36 tons while the data show it exported more than 18 tons. The same is true also for Kenya, Burundi and Chad.

A cause for some concern is the situation in the area of Sahel where Jihadist groups are trying to gain control of the greatly expanding market with the combined annual production of Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso amounting to around 50 tons per year. In Zimbabwe, on the opposite part of the continent, a declared exponential increase in production gives rise to suspicions that it concerns South African gold illegally bought and sent to Dubai.

Within this framework, another element that strikes the eye of analysts and which needs to be focused on is the partnership between the Eastern African countries and the Emirates which, through massive investments exceeding $250 billion, gained control of ports and infrastructure, thus participating in the African section of the Chinese Silk Road. This has made them become actors in local political life by interfering in the internal crises of various countries, and support by way of money and arms to various local groups.

Filippo Romeo