DR.Congo/Nigeria/Ghana. Towards new life.

On a hill in the city of Bukavu in the south of the DR Congo, a centre has been built to take in girls accused of witchcraft. In the deep south of Nigeria, a Sister fights against ancient beliefs and in a rural diocese of Ghana, the Church works to give hope to many children.

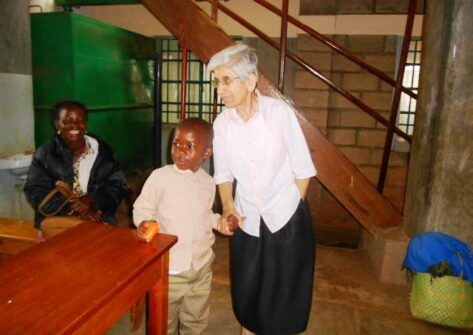

Her face is serene and smiling as she caresses one of the little girls she looks after at the Ek’abana house on one of the hills of Bukavu, in the Kivu region in the south of the country.

The centre has become a place of refuge for many little women who one day were called witches. Some are only five, some about twelve or older. Some have been beaten, others thrown out of their homes and others were subjected to attempted lynching. Sr. Natalina takes all of them in and listens to them. Every day, these little girls present a problem whether great or small to which she gives a solution, especially by encouraging, urging, calming and reassuring them. She is aware that her task is to bind up their broken hearts. Ek’abana has two meanings in the Bashi language: ‘The home of the children’ and ‘The children have a home’. Natalina Isella is a seventy-year-old Italian Sister who has spent more than forty years in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Sr. Natalina says: “Sorcery is a way of finding an explanation for a life of suffering. Of course, it is not the only explanation. There is also the break-up of families and the child of a previous marriage of the husband or wife is often accused; there are also the little ones born on the roads from extremely poor and girls who have been raped; ignorance, too, makes people accuse the neighbour’s girl of causing some illness or death. Most serious of all, there are small sects led by greedy pastors who mix Christianity with a lot of superstition and presumed spiritual powers. Behind these accusations of sorcery, there is almost always one of those fake saints”.

They have deep wounds, these little girls. They have been told: “It was you who killed your mother”; “It was you who made your playmates sick”. They are treated like the condemned and thrown out onto the street.

What takes place in the minds and hearts of little girls when they are called sorcerers? In years to come, will they ever forget such a traumatic experience? Sr. Natalina says: “These are the questions that we must ask ourselves when we are faced with these children and hear the stories they cannot tell without being overcome with emotion.”

Sr. Natalina is a member of the Women Disciples of the Crucified, a small religious Institute of the diocese of Milan founded by Barnabite Gaetano Barbieri in 1964. She first came to the Congo in 1976. First, she used to look after poor families, and then she took care of former child-soldiers, after which she worked in a literacy programme for women. The missionary Sister recalls: “It was 22 January 2002 when they brought me a group of nine homeless girls accused of witchcraft. What could I do? Leave them to sleep on a piece of cardboard? I took them in and began this work of mine. We had a small house and we arranged to be what we now call Ek’abana. In a matter of a few months, thirty more girls came to us: it was like an explosion”.

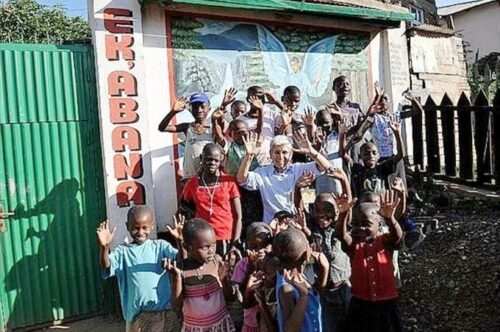

Today Ek’abana has about fifteen girl residents. Their number changes continually since their stay here is just the first of many stages on the long road to recovery. Each of them needs a family and each one is a particular case: some need to restore relations with their parents and siblings while others need to find grandmothers, aunts or cousins to take care of them. They need to go to school and learn a trade. In the past nineteen years, more than 450 girls have passed through Ek’abana and are now enjoying a ‘normal’ life. The house is also home to about twenty tiny unfortunate infants who were abandoned or left as orphans.

The tiny but tenacious missionary Sister has created a close-knit network of solidarity which provides the resources not only for Ek’abana but also a group of social workers who accompany the girls in their homes and collaborate with the police to sensitise the population against violence, abuses and accusations of witchcraft against minors.

Nigeria. A nun cares for abandoned children labelled as witches

Three years after taking in the little girl Inimffon and her younger brother, Sister Matylda Iyang finally heard from the mother who had abandoned them.

“Their mother came back and told me that she (Inimffon) and her younger sibling are witches, asking me to throw them out of the convent”, said Sr. Iyang, who runs the Mother Charles Walker Children Home at the Handmaids of the Holy Child Jesus convent. Such an accusation is not new to Sister Iyang.

Since opening the home in 2007, Sr. Iyang has cared for dozens of malnourished and homeless children from the streets of Uyo, the state capital of Akwa Ibom, in South Nigeria; many of them had family who believed they were witches. Witch profiling and the abandoning of children are common on the streets of Akwa Ibom.

If a man remarries, Sr. Iyang said, the new wife may be intolerant of the child’s attitude after being married to the widower, and as such, will throw the child out of the house.

“To achieve this, she would accuse him or her of being a witch”, Sr. Iyang continued. “That’s why you can find many children in the streets and when you ask them, they will say it’s their stepmother who drove them out of the house”.

She said poverty and teenage pregnancy can also force children into the street. At the Mother Charles Walker Children Home, where most of the children are sheltered and sent to school on scholarship, Sr. Iyang demonstrates the Catholic Church’s commitment to protecting child rights. She said most of the malnourished youngsters the order receives are those who lost their mother during childbirth “and their families bring them to us for care”. One of the important activities for Sr. Iyang is tracing and reunification. The process begins with parental verification by gathering information about each child and their location prior to separation. With the information in hand, an investigator drives to the child’s home village to verify what has been learned.

The process involves community chiefs, elders and religious and traditional leaders to ensure that each child is properly integrated and accepted in the community. If that fails, a child will be placed in the adoption protocol under government supervision.

Since opening the Mother Charles Walker Children Home in 2007, Sr. Iyang and the staff have cared for about 120 children. About 74 have been reunited with their families, she said.

“We now have 46 left with us”, she said, “hoping that their families will one day pick them up or that they will have foster parents”.

Ghana. A new chance at life

“I was about four or five … I came here because I was accused of witchcraft and I was condemned by my family and my community”, said Sarah, aged 12. When Sarah was four years old, she was wrongly implicated in the deaths of fifteen people in her community, simply because she had a speech impediment. In accordance with local customs in parts of northern Ghana, some people in Sarah’s community believed the little girl to be a ‘spirit child’. Under these customs, any child born with a disability or whose mother dies during their birth may be considered a bad omen, and their lives placed at risk.

Many in Sarah’s community, including her own family, became furious at her inability or unwillingness to speak and defend herself against the allegations, casting her out and threatening to kill her.

Thankfully, Sister Stan Therese Mumuni and the local Church were made aware of the imminent danger Sarah was in. Sister Stan recalls fighting – almost physically – to save Sarah from a terrible fate and give her a new chance at life.”When a child is born with a physical defect, they think it is a child with an evil spirit, and they have to get rid of such children; and we say that this cannot be done”, explained Bishop Vincent Sowa of Yendi. To rescue children from this practice, the diocese supports the Nazareth Home, run by Sister Therese Stan.

“These children have a wide variety of disabilities: malformations, blindness, Down syndrome, syphilis. All these children have been accused of witchcraft and have been thrown out of their communities and families, and have been threatened with death”, explained Sister Stan. The home rescues these children and takes full responsibility for them.Sister Stan has dedicated the last decade to running the Nazareth Home for God’s Children in the Diocese of Yendi in Ghana, a haven where children like Sarah are given shelter, nutritious meals, healthcare and education as well as unconditional love.

At the Nazareth Home for God’s Children, the children receive quality education so that they may one day gain employment and provide for themselves. Sister Stan’s dream is that one day they will return to their home communities and show how the love and support of the Church has empowered them to develop and reach their goals.

Rose Mary Mutesa