Central African Republic. Forgotten and invisible children.

When conflicts subside, children used by armed groups become the most forgotten victims. In an area in the south of the Central African Republic, some of them are trying to reintegrate in the face

of great difficulties.

Sitting under a tree, in a large courtyard next to a water pump where several women come to fill their jerrycans, 20 teenagers wait in silence. It is just before eight in the morning and the office of the NGO that called them to the Central African city of Alindao is about to open. They left their village 15 kilometres away, very early, before 5 am. The local chief, Arthur, gives them one last piece of advice before the social workers start calling them one by one.

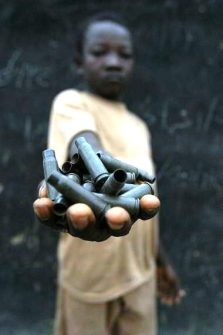

The twelve boys and eight girls belong to the category of “children associated with armed groups”, a nomenclature that the institutions that help these minors describe as more accurate than that of “child soldiers”, as they have been known for decades. These are minors who have spent time in militias or rebel groups as fighters, or who have been forced to perform other tasks, such as porters, spies, cooks, guards or, very often in the case of girls, sex slaves.

‘Children associated with armed groups are young people who have spent time in militias or rebel groups as fighters. File swm

“When the militias came to our village, neither these children nor their parents had any choice,” Arthur recalls. “They selected all the children they thought could be useful to them and forced them to go with them.” As state authority gradually returned to the area, three years ago some rebel groups disbanded and the minors who were in its ranks returned to their homes. “Almost all the leaders of the various guerrilla groups were conscripted into the army, but the children returned traumatised, many sick or with unhealed wounds. Others disappeared or were believed to be dead,” Arthur continues.

Today, the NGO staff conducts an individual interview with each of them. Once their family and social profile are known, an attempt will be made to provide those who were unable to return to school with training courses in mechanics, bricklaying, commerce, sewing, etc., so that they can practice a trade that will facilitate their reintegration.

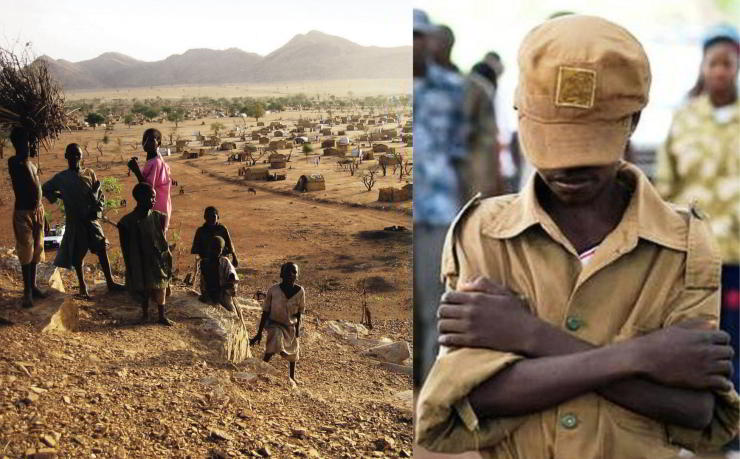

Village women with their children. “”When the militias came to our village, neither these children nor their parents had any choice”. File swm

The prefecture of Basse Kotto, in the south of the Central African Republic, was one of the most affected by the crisis that erupted in the country in 2013 when the Muslim-majority Seleka rebels took power. Following the intervention of international forces, the Seleka fragmented into several militias. One of these, the Unit for Peace in Central Africa (UPC), led by warlord Ali Darrassa, settled in the central and southern areas of the country including Basse Kotto, recruiting mainly young Peul ethnic groups, semi-nomadic shepherds who follow the Muslim religion. At the same time, anti-balaka militias, which emerged to fight the Seleka, and therefore the Islamic community, spread across the

area like an oil slick.

Anti-Balaka militia. The anti-balaka forced countless minors to join their ranks. CC BY-SA 4.0/Clementalline

The worst moment of the crisis erupted when, in November 2018, the UPC – supported by a group of young radical Muslims – attacked a camp for displaced people in Alindao, killing 120 civilians and wounding hundreds more. The conflict entered a spiral of endless violence, and in the surrounding villages, everyone was forced to choose a side, leaving no room for neutrality, under penalty of being branded as traitors. The anti-balaka forced countless minors to join their ranks, in a dynamic of relentless confrontation between Muslims and Christians.

A few years ago, most of the anti-balaka groups disbanded and today government soldiers, supported by Russian mercenaries from the Wagner group, exercise some control over the affected areas. But the UPC is still active in various areas, where it extorts money from the civilian population and carries out sporadic surprise attacks, often on the roads, where traffic is not without risks.

An uncertain number

Children associated with the armed groups have been the big losers of the crisis years. In the villages where the Anti-balaka recruited minors until recently, they have returned home empty-handed and with a myriad of problems. A community network, RECOPE (Community Child Protection Network), supported by several humanitarian organizations, works with local leaders to support these children. Its president assures that “it is almost impossible to know the exact number of minors who have spent years with the militias, because there is still a lot of insecurity in the area and many of the boys who were forced to fight are hiding, because they are afraid of possible reprisals from the other side, especially in the most remote villages of Alindao”. RECOPE members sensitize people in the villages to understand the problems of children who the armed groups have abandoned and to support them as best they can. They present lists of names to NGOs so that, after appropriate checks, they can access reintegration programs.

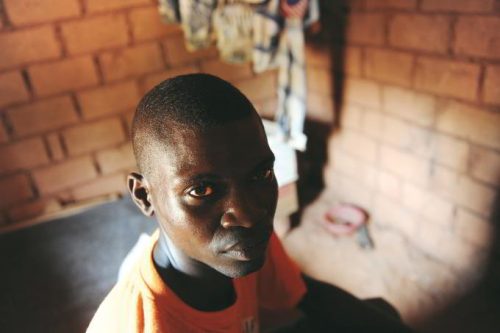

It is difficult to know the exact number of minors who have spent years with the militias. File swm

One of them, Thierry, 18, now lives with his parents in a suburb of Alindao, where he combines his studies with two small businesses: a kiosk where he sells various items and a stable where he raises pigs. Thierry recalls how, at the age of 14, the Anti-balaka came to his area one day and forced him to go with them: “They made me do military training, they gave me a rifle and I spent two years fighting the UPC,” he explains. He and other boys of his age also took part in attacks on villages of the Peul communities, almost always looting and burning their homes.”One day I managed to escape. I went back to my parents and since then I have stayed at home, I have not moved from here,” he says. Thierry has been supported with therapies to overcome the trauma he has suffered. The same NGO helped him to resume his studies and with the course in which he learned the basics of small business management.

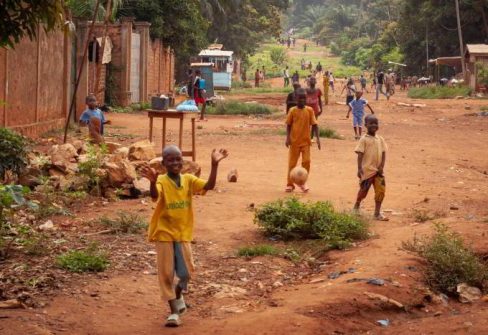

Central African Republic. Kids playing football on the streets. An apparent calm reigns.

Shutterstock/sandis sveicers

Today, in Alindao, an atmosphere of normalcy and apparent calm reigns. Christians and Muslims meet at the market, at the same hospital, in the same schools, and even at football matches organized by young people.

Overshadowed by the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, the Central African Republic is no longer in the spotlight of the international community. Their low-intensity conflict hardly attracts attention. In most of its territory, the weapons have fallen silent, but in the hearts of the victims, the traumas suffered continue to damage people, especially the minors who have been used by the armed groups. Some will be able to find opportunities to move forward. Others, in the most remote areas, will remain invisible. (Open Photo: File swm – Pierre Holtz /UNICEF)

José Carlos Rodríguez/MTM