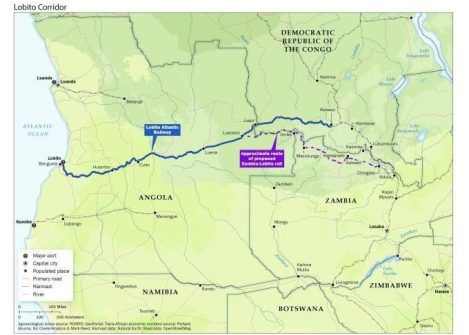

Angola – DR Congo – Zambia. The Lobito corridor. The mineral railway.

This infrastructure will change the trade routes of Southern Africa. It will be used, above all, as a route for the transport of critical raw materials and strategic minerals. American, European

and Chinese interests.

It was in 1902 that the Portuguese administration undertook the construction of the Benguela railway, 430 km from Luanda. As often happened during Portuguese colonialism, a rich British entrepreneur, Robert Williams, was chosen to carry out the work. The idea was to connect the port of Lobito (in southern Angola) by rail with Katanga, in DR Congo, rich in copper. The work was ready in 1929 and was immediately very profitable. It became even more so in 1973 when the Southern Rhodesia-Zambia border was closed. The Angolan civil war destroyed a good part of this infrastructure, which therefore had to be almost entirely rebuilt when the conflict ended between the Angolan government and Savimbi’s Unita (Savimbi died in 2002).

Map: Usa

Infrastructure and China’s role

Financing began to come from China, given Western reluctance towards Angola, whose government was recognized by the United States only in 1993. In 2004, an agreement between Luanda and the Export-Import Bank of China provided for an exchange of oil and infrastructure, worth $2 billion. Three railway routes were built, all heading east, starting from the ports of Luanda, Lobito and Namibe, as well as the redevelopment of Luanda airport, the construction of the industrial centre of Viana and roads in 17 provinces of the country.

After China, other countries entered to finance infrastructure and housing in Angola, including Brazil, Portugal, Spain, South Africa and Canada. The port of Lobito has also seen important Chinese investments, as well as that of the Angolan government, for around 1.2 billion dollars. The port will have the capacity to handle approximately 4 million tons of goods, while an airport was built in Catumbela, halfway between Lobito and Benguela, with Angolan national funds and thanks to the intervention of the Brazilian Odebrecht, the Portuguese Somague

and the Cuban Imbondex.

American interests

If China was the first country to understand the importance of the Lobito Corridor, in recent times a central role has been assumed by the United States which will probably continue to do so in the coming years. Through the African Finance Corporation (AFC), President Joe Biden’s advisor on infrastructure and energy, Amos Hochstein, recently said in Lusaka that the AFC has already allocated $1 billion to build or improve the rail line of the Lobito Corridor up to Zambia.

Lobito Port is the second largest seaport in Angola. CC BY 2.0/ David Stanley

The line should become operational by 2028. American interests essentially concern the Zambian side. Zambia, in fact, is becoming one of the reference countries for US policy in the region, thanks to a huge boost to its economy. Lusaka and Washington signed a bilateral agreement on 30 March 2023, while the European Union also recently agreed with what Washington proposed. The EU joined the financing of the Lobito Corridor, having signed, together with the USA, an agreement initially stipulated between the African Development Bank and the governments of Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, together with the Africa Finance Corporation.

The American and European enthusiasm for the Lobito Corridor is now so passionate that this infrastructure was even the subject of discussion at the G20 in New Delhi, in September 2023. Complete with statements from the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, who spoke of a “turning point” not only for the entire regional trade

but also for the world.

Lobito, what is at stake?

The veritable race to finance the Lobito Corridor has very specific causes: the mining sector of Zambia and DR. Congo. In these countries, in fact, there are raw materials such as copper, cobalt, manganese, zinc, but above all the new “white gold”, lithium, necessary for electric car batteries and more.

Today, Africa holds 5% of the world’s lithium reserves, of which Australia is the largest producer. However, there are only two countries that currently manage to exploit it: Zimbabwe, the sixth world producer, and Namibia, where the Chinese company Xinfeng Investments, which manages the Uis mine, has been accused by the NGO Global Witness of exploiting excess local labour and of bribing the Namibian government to receive licenses, which should have been granted to small local consortia. In Zambia there are enormous copper deposits: it is the second African producer after the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Lobito Corridor is to become the third most key corridor in the SADC region by 2050. Photo: Government of Angola.

However, the declining production in recent years, due to technical difficulties, has induced the government led by Hichilema (in office since 2021) to commit more to this sector, seeking partnerships to energize the entire local economy. The other element that Westerners covet is cobalt, of which Kinshasa is the world’s leading producer. Cobalt is also necessary for electric cars and the Democratic Republic of Congo has the Kisanfu reserve, in the south-east of the country, among the largest in the world but currently unexploited.

Competition without borders

Following China, Western governments have also understood the importance of this strategic mining area and the Lobito Corridor, starting a competition without borders which, at the moment, is seeing China still prevailing in Angola, while the United States and the European Union are seeking closer collaboration with Zambia and DR Congo. The latter country is experiencing a profound crisis, and not just today, with neighbouring Rwanda.

For the future, there are at least two elements to evaluate. On the one hand, the cases of Namibia and Zimbabwe should set a precedent: the new appetites for mineral resources, once secondary, risk repeating unsustainable models of human and environmental exploitation, as has historically happened with oil and gas. On the other hand, the movement towards Lobito, resulting in important commercial traffic on the Atlantic coast, could further impoverish the other side of the continent, that of the Indian Ocean, already affected by conditions of poverty and marginalization which could worsen today.(Open Photo:123rf)

Luca Bussotti