Always On the Move.

The Bororo culture is one of movement. There are different sorts of movement. First of all there is the perol, ‘the great movement’, mostly for political or environmental reasons.

It is a real migration and happens only in exceptional cases. For example, the great perol that brought part of the Wodaabe into the territory of Kawlaa, took place starting in 1910. Then there is the seasonal migration (baartol) which is a regular event and is caused by the ecological factors of the different areas. This movement determines the coming and going of the nomads; their centre, however, remains their affiliated territory.

The movement to the north, during the rainy season, is called njakake. When the rains are over, the Wodaabe return to the south where they spend the dry season. This migration is called djolol.

The goonsol, instead, connects two grasslands within an ecological unit. Shorter than the goonsol is the dimbdol, which takes place between two ‘points of water’. Moving during a girsusaki (short movement), the nomad can see his point of departure.

Livestock is their all

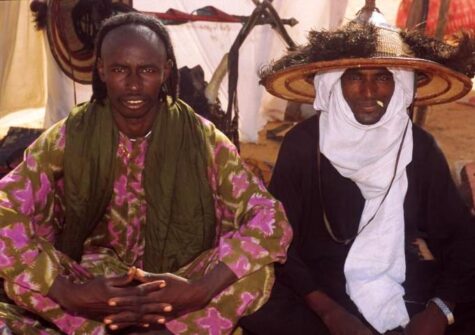

The family (wuro), whether nuclear or extended, is the fundamental unit of the social and economic life of the Wodaabe. It usually consists of a man, his wife (or wives) and the children. Each family has its own cattle. The ideal of an elderly Bodaado is to leave a legacy of more cattle than he himself received to his children.

Among the Zebu, the cattle are at the centre of Wodaabe interests. The animals are rarely killed although their milk and dairy products are used. A Bororo proverb says: ‘Without milk we are like the dead’. However, the animals can be bartered for other consumer goods with neighbouring peoples or people met during transhumance.

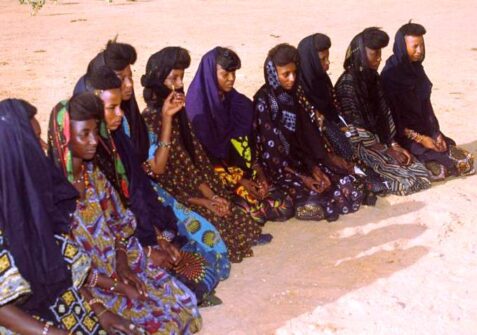

Unlike other tribes, among the Bororo the cattle also belong to the women. Each girl receives some heads of cattle as a dowry so that her survival may be assured, apart from Zebu espousal ties that are often very weak. The relationship with the animals is indissoluble. Each boy receives a calf while he is still very young. A Bororo lives off his herd. Each animal has its name and each boy is given the name of an animal. Only during feasts is it allowed to sacrifice an animal.

Animals mark the time

The day of the Bodaado is divided up by the life of the animals. Before sunrise, (tiima pinde na’i), the inspection of the animals takes place. At dawn, the small calves are released from the cord with which they were tied the night before (yoofa nyalbi) and allowed to suck milk from their mothers. Then the milking (bira na’t) begins. The animals are set free to graze (wammunde maajunde). At midday (iftol), instead, the herd rests; the small calves are kept separate from the adult cattle (nyalbi kodaama).

In the early afternoon (hiirtunde), the herd is allowed to graze. In the late afternoon the small calves are tied to the cord that divides the encampment (daangol): the hour is called habba nyalbi (‘then the calves are tied up’). In the evening (na’i njaa’oo or dudana na’o), the herd returns to the encampment and the fires are lit in the corral (du-dana na’). The milking follows (lira na’). Before retiring, the pastors tie the older calves to the cord (daangol). During the night (soggunde), the adult animals are sometimes allowed to graze.

Marriage, by law and for love

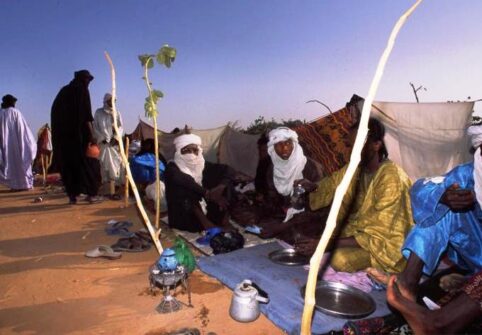

Being nomadic pastoralists, the Wodaabe are constantly moving in search of new grazing. They say: ‘We are like the birds: when we finish pecking we fly away’. They are well versed in knowledge of plants and spells and constantly use talismans and amulets. They live in temporary encampments composed of simple huts made from bushes and straw.

Marriages take place within the ethnic group and are of two types. The more prestigious form is that which takes place through engagement (kooggal). In this case, a male child and a female child are declared ‘engaged’ from a most tender age and they marry once they reach puberty. Since this sort of marriage is really ‘arranged’ by the parents and the families and demands various transactions involving animals, the tendency is to seek the future spouse of the son among paternal relatives; a cousin is often chosen. Most of first marriages are of the kooggal sort. The second type of marriage called teegal (free contract) is resorted to by people who are divorced, by those who have been left without a partner or by men who want a second or third wife. In this case, it is not necessary to choose the wife or husband from within the lineage of affinity; often a non Bodaado may be chosen. In principle, the teegal marriage certainly denotes mutual love, sentiments and passion but also an element of hostility since the wife is considered ‘stolen’.

In any case, the marriage is considered improper if it takes place between related lineages.

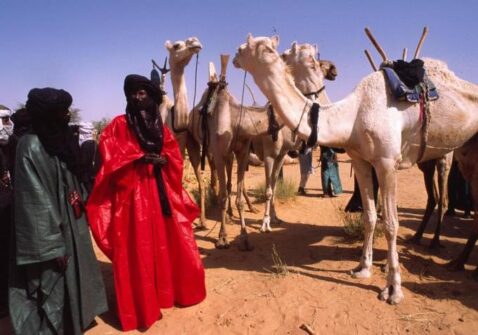

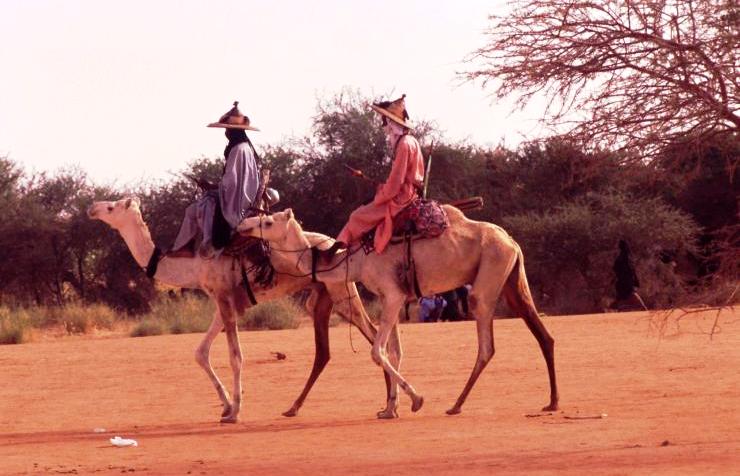

Reserved but jovial and with refined manners, the Bororo Wodaabe see themselves as courageous warriors. This is a necessary quality for survival in an area of continual tension and ethnic clashes. The areas of their transhumance border to the south with the sedentary farmers and, to the north, with the Tuareg whose warlike spirit is well known.

Unlike that of their neighbours, Wodaabe society is one of equals in solidarity but independent, one that has never had any form of slavery. The Bororo hate bonds, fences or being faced with limits. They are born nomads who do not recognise ties and do not wish to blend with other peoples. Besides their livestock, the Bororo take with them the most beautiful jewels and amulets; the women also take some empty gourds to use as containers and the men carry a long sword. They do not use tents. There is no hierarchy in their social organisation. The head of the clan, the ardo, simply gives counsel and his power is based on his moral authority. (F.M.)