Algeria. The call of the desert.

The Tassili Ajjer massif is home to the world’s largest rock art museum and incredible rock formations shaped over millions of years. And in the Hoggar Mountains, you walk between earth and sky, enveloped in silence.

Southern Algeria is a treasure chest of secrets. In this remote area of the Sahara, between the geological folds of two national parks – Tassili n’Ajjer and Tassili Hoggar – stands the largest museum

in the world of rock art.

The Tassili Ajjer. Southern Algeria is a treasure chest of secrets. File swm

It was a soldier of the French colonial army, Henri Lhote, who first provided information and catalogued and studied engravings and paintings that tell the story not only of the desert but of man himself, representing moments of daily life, the fauna and flora of an environment now disappeared under the sands, the spirituality and ancient rituals of our Saharan predecessors. On the Tassili n’Ajjer plateau, which is the natural border between Libya and Algeria, at about 1,800 meters above sea level there is a small miracle: near the town of Tamrit you can still see about two hundred specimens of Cupressus dupreziana, what remains of a forest that once was.

The pearl of Tassili

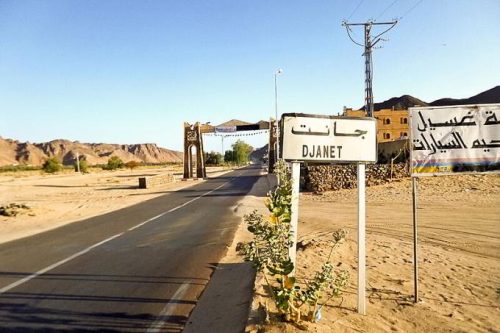

Djanet is the capital of the province of the same name and a starting point for discovering one of the most fascinating and beautiful regions from a cultural point of view, not only in Algeria, but in the entire Sahara. Djanet started as a small military outpost during French colonization (at the time it was called Fort Charlet), of which the small fort on the hill overlooking the oasis remains. Considered “the pearl of Tassili” thanks to its immense palm grove, the city is made up of five villages: El Mihan, Adjahil, Azelouaz, Ain Berber, Tin Katma; the latter is the ancient heart, and also the commercial centre, of the oasis.

Djanet is the capital of the province of the same name and a starting point for discovering one of the most fascinating and beautiful regions in the entire Sahara.CC BY-SA 4.0/Brahim Djelloul Djanet. CC BY-SA 3.0/habib kaki

Arriving at sunset at the entrance to the ksar (fortified village) of El Mihan means having in front of you a fascinating nativity scene, now semi-abandoned. With its unfading charm, Djanet is the main gateway to an ecomuseum that extends for 80,000 square kilometres, in an area that is sometimes covered with dunes but mostly rocky: the soft sandstone rocks have allowed the preservation, according to the most recent estimates, of 70,000 paintings and rock engravings, a number that is sure to rise with the reconnaissance resumed in recent years. The rare visitors walk on the plateau among lithic finds and ceramic fragments that appear on the surface of the sand: arrows, chisels, scrapers and millstones, witnesses of a life characterized first by gathering, fishing and hunting, then by livestock farming. Touching one of these ancient tools of human history is an emotion possible only in a few other places in the world.

The silence of the Hoggar

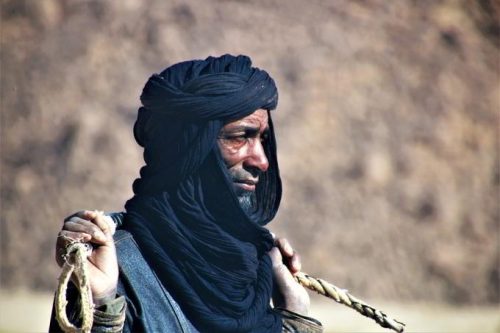

The spectacle continues in the Tassili Hoggar, a massif that takes its name from the Tuareg population that traditionally lives there, the Kel Ahaggar. It starts from Tamanrasset, the capital, at 1,400 meters above sea level, an ideal stage for romantic adventures narrated in books and films that have made it famous among the European public. Oral traditions say that Queen Tin Hinan, a legendary heroine from whom the local Tuaregs originated, lived in this area. To reinforce the narratives that assert the historical authenticity of Tin Hinan, a colossal megalithic monument near Abalessa, about eighty kilometres from Tamanrasset, is referred to by all as “the tomb of Tin Hinan”.

This region is rich in rock art.File swm

This region is also rich in rock art, but the numbers are not as impressive as those of the Tassili Park. The volcanic region of Hoggar is famous thanks to Charles de Foucauld: French, a Trappist friar, he moved in 1905 to Tamanrasset, where he died in 1916. He founded a small hermitage on Assekrem, a peak of 2,800 meters high, still today a destination for pilgrims and tourists.

Braving the climate and the hardships, they push themselves up to the reddish peaks of the Atakor chain, Mount Tahat, the highest peak in Algeria (2,908 meters), and Ilamane (2,739) to admire sunrises and sunsets in absolute silence, gathered in a muffled atmosphere of solitude and deep spirituality.

The fascination of the M’zab

The Algerian Sahara is full of beauties to discover. Ghardaïa, the capital of the Mozabite pentapolis, where time seems to have stopped and people live clinging to the slow rhythm of daily life and traditions.

The five villages of the M’zab were built in a natural basin for defensive purposes: the Mozabites, puritans of Islam, were fleeing persecution and in Ghardaïa they found the place that has allowed them to survive

to the present day.

Great mosque of Ghardaia.CC BY-SA 3.0/Gigi Sorrentino

In Ghardaïa nothing is by chance and no detail is overlooked: the walls of the houses are plastered so that the sun’s rays do not heat the inner spaces of the homes, completely bare of furniture but full of niches and built-in wardrobes; the flow of water from the public fountains flows away to irrigate date palms whose fruits are still divided equally among the inhabitants; nothing disturbs the quiet of the residential neighbourhoods because commercial activities are concentrated at the base of the villages, built in a cone around the mosque, on natural hills, with an almost perfect urban layout. Ghardaïa is unique, yes, like its inhabitants, men in traditional clothes consisting of pleated trousers and women who look like white ghosts, covered entirely (except for one eye) as they furtively wander through the narrow alleys of the villages.

A nearby world

West of Ghardaïa, the fascinating “gardens of Saura” open up: in a desert territory, flat and hostile but caressed by the immense dunes of the Western Erg, there are numerous ancient Berber villages built of clay, mud and straw: small fortified oases, which developed thanks to trade with black Africa and the West. In the fifteenth century, a Venetian merchant, Antonio Malfante, left the Serenissima to reach the small oasis of Adrar on the back of a camel in search of fortune: in his letters to his Genoese friend, he recounts his adventure but above all the defeat that led him, the first white man to venture so far south, to return

home empty-handed.

The Mediterranean has been a fruitful space of relationships and trade in which multiple human destinies have intertwined. File swm

He is not the only European to have entered the country in the past: Isabelle Eberhardt, a Swiss explorer and writer of Russian origin, travelled disguised as a man in the desert at the end of the nineteenth century, leaving us important testimonies of places and situations closed to women in a society that was male-dominated at the time. In the same period, the painter Étienne Dinet lived in Bou Saada, 250 kilometres south of Algiers, where his house was transformed into a small museum, immortalizing with his brush the daily life of the oases in masterpieces now preserved at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The Mediterranean has never represented an obstacle between Europe and Africa, rather it has been a fruitful space of relationships and trade in which multiple human destinies have intertwined. (Open Photo: File swm)

Oriana Dal Bosco/Africa