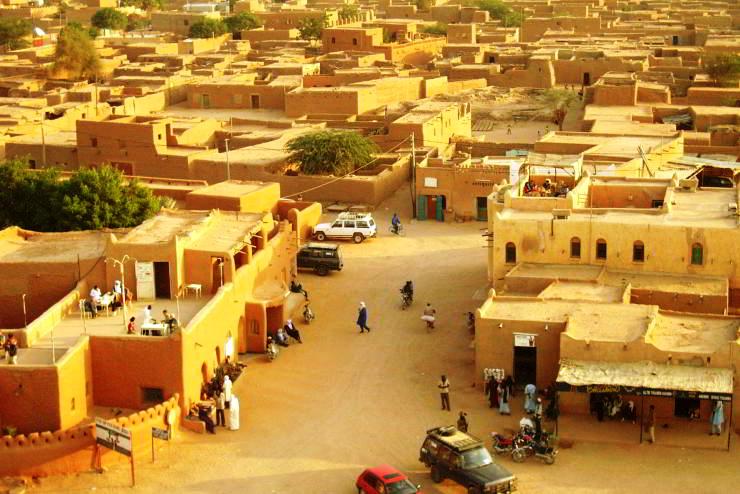

Agadez. The Gateway to the Sahara.

The city in the north of the country is the main hub of the migration routes towards the Mediterranean. In 2016, the EU imposed a law that criminalized the transport and activities related to fleeing people. The coup junta repealed it. Return to “normality”.

Ousmane Mamou, a young Guinean, is waiting in front of a petrol station in Agadez in the middle of the desert of Niger. In life, Ousmane is a passeur: he organizes the journey of migrants who want to reach the coast of the Mediterranean and from there try to reach Europe.

Until a few months ago it was impossible to have an open conversation with people who carry out this profession. But now everything has changed: “I came back because I heard that the military junta had repealed that law and I came to take revenge. The policemen who treated us like traffickers and bandits, today feel ashamed,” he explains.

“That law” is the controversial Law 2015-36 which criminalized the transport of irregular migrants with heavy fines and sentences of up to ten years. Last November the new military junta, the National Council for the Protection of the Homeland (CNSP), which took power in Niger at the end of July 2023, announced its abrogation.

The city administers a desert region that covers half the territory of Niger. File swm

Agadez has always been considered the “Gateway to the Sahara”. The city administers a desert region that covers half the territory of Niger and in recent decades has become a pole of interest for Western European leaders, because some of the main migratory routes that lead from sub-Saharan Africa to the Mediterranean pass through here. The transit of migrants to Libya and Algeria has always been considered a legitimate activity that provided thousands of families with a decent income and created related activities and economic impulse.

Suddenly in 2016, after the entry into force of the law adopted under strong pressure from the European Union, hundreds of drivers, facilitators and passers usually based here were prosecuted and arrested. Ousmane experienced all this. Arriving in Agadez as a migrant, he decided to enter the business. In 2021 he was arrested by the Nigerien police and after two and a half years in prison in Niamey, he was released. A few weeks ago, he returned to the scene.

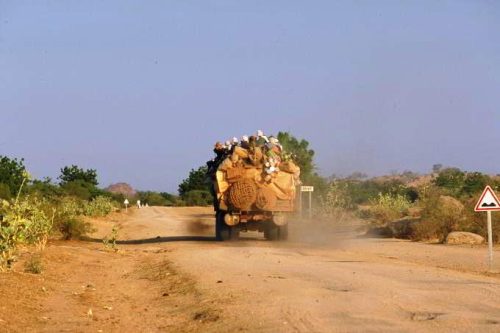

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in 2023, 60 thousand migrants crossed Niger towards Libya and Algeria. File swm

In the Dubai neighbourhood, homes are barely visible behind high iron gates. Ousmane enters a “ghetto” to meet some clients. “Ghettos” are houses used to house migrants in transit. When the 2015-36 law was in force, migrants were forced to live locked up in these homes for months, in difficult conditions, until the day the facilitators managed to help them leave. There is no furniture inside, people sleep on the floor on mats. Outside there is usually a courtyard where people eat and from there is access to common latrines. “Everything had to happen in secret. Upon arrival, we had strategies to get the migrants out of the bus station and bring them here,” explains Ousmane. “We would make contact with people well beforehand in their countries, speaking in code due to the risk of wiretaps”. The passer says that waiting for the right moment to leave the pick-up in the desert was crucial and “it took place at night over unbeaten routes”.

In fact, Law 2015-36 did not stem the flow but only forced passers and migrants to avoid official roads, using more dangerous routes, where there were neither points of reference nor the possibility of asking for help. The data shows that irregular immigration to Europe from the Mediterranean has increased, as has the number of victims in the desert who remain mostly undocumented. Kaba, a migrant from Sierra Leone, is not afraid of this. He is waiting for more money from friends in Europe to be able to continue his journey and become an electrician there. “I have been thinking about it for a while and as soon as I heard about the revocation of the law, I decided to leave. They told me it’s faster now. They used to ask you questions and arrest you for your documents. Now all you need is the money.”

According to the mayor of Agadez, 98% of the vehicles that leave Agadez for the various destinations in the north are official. File swm

In the house opposite, a Senegalese passer has temporarily left the management of the “ghetto” to Khalifa, an Ivorian boy with a troubled past. A former bus driver, Khalifa fled after a fatal accident that almost led to his lynching. Since the law was repealed, he and others feel relieved “because departing vehicles fill up more quickly than before and leave more often.” Now he’s trying to save money for the crossing: “I’ve been informed that to get from here to Libya it takes 300 thousand CFA francs (457 euros), but I want to get more together so I will also have something to save my life along the way.” In fact, there is the risk of being stuck in the desert and being attacked by bandits or terrorists.

Bamira Hassane is the switchboard operator of the emergency number of Alarm Phone Sahara (Aps), an NGO that helps migrants in difficulty in the desert. Previously she received 10-20 calls a day, while after November she received double that: “These are mostly requests for health support and above all emergency calls from the desert or people expelled from neighbouring countries.”

In the desert there is the risk of being stuck and being attacked by bandits or terrorists. File swm

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in 2023, 60 thousand migrants crossed Niger towards Libya and Algeria. Now, however, it is difficult to have data on the flow of people because after the coup the activity of humanitarian organizations on the spot has decreased. In the city, in the area around the bus stations, stalls sell everything you need for the trip: clothes, food, water cans and cell phone batteries. The houses around the central station have been used as garages, where several pick-ups in line are tuned up and loaded with as much goods as possible. In the office of the transporters’ union, Abdou Amma is among the most experienced passers back in business. For 19 years he sent ‘people from all over Africa’. Once the law came into force, he fled to avoid arrest. According to Abdou, “The EU promised us help, but nothing arrived. Many drivers have turned to drug and weapons trafficking, as well as banditry.”

Now Agadez “has become a paradise again, because everyone lives on migration from the merchant to the passer, from the restaurateur right up to the Municipality. Each migrant pays a tax of one thousand CFA.” By all accounts, migrants today travel in better conditions because every Tuesday the transporters take advantage of a military convoy that goes towards the northern borders.

The mayor of Agadez, Aboubacar Touraoua, confirms that everything is authorized by the authorities of Niamey: “98% of the vehicles that leave Agadez for the various destinations in the north are official. Before it was the opposite, only 30% showed up. Now we know who comes in and out.” For the mayor, the agreements made with the EU were accompanied by promises of support, but in reality “everything was aimed at bringing the European borders here. Now, however, everything that does not respect our sovereignty is called into question by the new government. This is why we are all on their side.” (Open Photo: Agadez: the “Gateway to the Sahara”. File swm)

Marco Simoncelli