Afghan women today: invisible and imperceptible, but they still resist.

First, they were forced to cover themselves from head to toe, to see the world through a net. Then, they were banned from studying beyond the fifth grade, from working (even when they were their families’ sole breadwinners), from walking without a male guardian, and from going to gardens and gyms.

They closed shelters for victims of domestic violence and beauty salons, rare points of conviviality. And now they cannot speak in public, sing, laugh or recite poetry – this in a country where “grandparents spoke to their grandchildren using Rumi’s verses and children grew up playing sher- jangi , the game of poetry”.The Taliban, who returned to power four years ago after two decades of war, have hardened rather than moderated (as they promised) the misogynistic policies that were in place from 1994 to 2001, during their first “Islamic emirate”.

A group of Afghan women wearing burqa walks in the street to go to the market. Since 2022, the Taliban have issued at least 70 decrees to strip women of their rights. Shutterstock/Pvince73

Since 2022, they have passed at least 70 decrees to strip half the population of their rights. Forced into marriages, many of them child marriages (parents sell their daughters for food), abandoned and unprotected when sexually abused, flogged, and stoned to death when accused of adultery, women were reduced to ghosts.

“Today in Kabul, a cat has more rights than a woman,” actress Meryl Streep said at an event at the United Nations headquarters in New York in October 2024. “A cat can sit on the porch of her house and feel the only thing on her face. It can chase a squirrel in the park [and] a squirrel has more rights than a girl in Afghanistan because the parks were closed to women and girls by the Taliban. A bird can sing, but a girl cannot sing in public.” The “slow asphyxiation” of Afghan women denounced by Meryl Streep had already been highlighted in a UN Women report published in August 2024: “The hard-won progress of the last two decades to achieve gender equality has been erased by oppressive directives that attack the very existence of Afghan women”, and the effects “are devastating”.

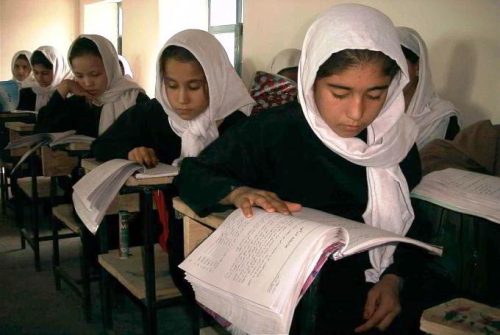

Young girls attend classes in Helmand Province. By April 2023, at least 80% of girls had no access to any kind of education. UNICEF/Mark Naftalin.

The first alarm bells went off when secondary schools were closed in March 2022, followed by universities in December of the same year. By April 2023, at least 80% of girls had no access to any kind of education. While some primary schools remained open, almost 30% of girls never entered them, due to “entrenched socio-cultural norms, prohibitive costs and because it is unsafe to travel”, especially in the most remote provinces. The situation “is even more serious for girls with disabilities: 80% have no access to education”. “The restrictions imposed by the Taliban will affect future generations,” UN Women warned. “By 2026, the impact of leaving 1.1 million children out of school and more than 100,000 women out of university will be linked to a 45% increase in the rate of early pregnancy and a 50% increase in the risk of maternal mortality.” The price of excluding women from the labour market costs Afghanistan about $1 billion a year, according to the United Nations Development Programme. Other projections indicate that “the national economy will lose $9.6 billion, equivalent to 2/3 of the current gross domestic product, by 2026, if women continue to be barred

from higher education.”

The price of excluding women from the labour market costs Afghanistan about $1 billion a year.

What the Taliban advocate as measures to “defend honour,” in a toxic interpretation of Islam that is followed by no other Muslim-majority country and is branded “hypocritical” because Kabul’s leaders are educating their daughters in Turkey or Qatar, “will condemn generations of Afghan women to a life of dependence.”

The oppression of women, in addition to extreme poverty, is fuelling a deep mental health crisis. The British newspaper The Guardian told the story of an 18-year-old girl who saw her dream of becoming a doctor dashed and was forced to marry a heroin-addicted cousin. “Feeling that her future had been stolen from her and she was left with two options – marry a drug addict and be miserable, or end her life – she chose the latter.” It was not an isolated act.Despite the suffering inflicted on them, many Afghan women resist, protesting in the streets or on social networks, risking arrest, rape, torture, or death. This opposition, “increasingly political,” emphasizes Sahar Fetrat, researcher for Human Rights Watch, “is the greatest fear of the Taliban,” who “insisted on reducing women’s voices and bodies to sources of sin.”

Women walking in a blue burqa on a dirt road in Kabul. 123rf

The resistance movement, which includes women from all walks of life, “is peaceful, young and diverse, courageous and optimistic,” says Afghan Fetrat, quoting the words of an activist: “We are not afraid of death. We are an immortal generation. Individual courage inspires hope.”

The current priority for women inside and outside Afghanistan is their campaign, launched in late 2023, for the UN to recognize and characterise as a crime against humanity “gender apartheid”, a term they coined during the first Taliban regime, invoking as a precedent “racial apartheid”, enshrined in international law since 1973.

Last October, there was some good news: the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that “it is sufficient to take into account only nationality and gender” to grant asylum to an Afghan woman. (Open Photo: Two women in burqas making a fist gesture against violence and for human rights. Shutterstock/chomplearn)

Margarida Santos Lopes