Catholic Radio Stations in Africa. Educating, Informing, Transforming.

There are more than two hundred radio, from Angola to Zambia reaching millions of people. They promote peace, human rights, education, health, and development. They endeavour to heal the wounds of traumas.

They are the voice of the voiceless, though sometimes silenced. Three stories of resilience and success: Radio Sol Mansi, in Guinea-Bissau; Catholic Radio Network (CRN) of South Sudan and the Nuba Mountains; Radio Ditunga in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Radio Sol Mansi has just celebrated its first twenty years as the most listened-to radio in Guinea Bissau. The Radio station was set up in February 2001 in a particularly difficult time for the country as it recovered from a bloody civil war.

From its beginnings, the Radio has been outstanding for its commitment to peace, reconciliation, and development.

“Sol Mansi means ‘dawn’ – the dawn of a new day, new history, new life, a new horizon”, explains Radio director Casimiro Cajucam.

Radio Sol Mansi began transmitting at Mansoa, sixty kilometres north of Bissau, the capital, using a small 250-watt limited capacity transmitter, but previously, in 2008, Radio Sol Mansi had been the National Radio of the Catholic Church.

A score of years after its founding, Radio Sol Mansi “is now one of the reference stations, not only in terms of listeners but also for its credibility”, especially because “it has always built bridges of dialogue between different religions and ethnic groups”, Cajucam affirms.

In August 2009, Radio Sol Mansi signed “a historic accord of collaboration” with Radio Coranica de Mansoa.

“Perhaps the first in the world to do so, the Catholic station broadcasts an Islamic programme and the Islamic station broadcasts a Catholic programme”, the director emphasises.

The Radio Sol Mansi programmes (one with most listeners is ‘Ten Minutes with God’) present all sorts of subjects, even the most sensitive, such as the genital mutilation of women, a practice only forbidden by law in 2001, under-age and forced marriages, something still very common in Guinean society, especially in internal areas. The programmes also touch upon such themes as the rule of law, democracy, justice and gender equality, corruption, professional ethics, and the social doctrine of the Church. “Our programmes are in line with the situation and needs of the country”, the director states.

At the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, Radio Sol Mansi “assumed a very important role – the director adds. With the churches closed, the Holy Mass, prayers and catechesis in two dioceses were provided via radio. Socially, we are continuing to work in the front line in awareness and prevention of the coronavirus”.

The director makes no secret of the pressure exercised, especially by politicians. He says: “Pressure comes mostly from the political class and the government elite whose strategy it is, on the one hand, to create fear among the journalists and, on the other, to keep them under observation. We had to keep silent only during the coup by the military on 12 April 2012. In effect, all the radio stations were shut down by the military coup organisers for 48 hours”.

At present, the studios of Radio Sol Mansi employ 22 men and 11 women. The station also has a network of 50 correspondents all over the country, “who enable it to be the voice of those excluded from the circle of communication”. Half of all news is broadcast in Portuguese and half in Creole (the language spoken by more than 90% of the population). Radio Sol Mansi also has a team of “child journalists who go out and conduct interviews and commentaries” intended for the young.

Radio Network

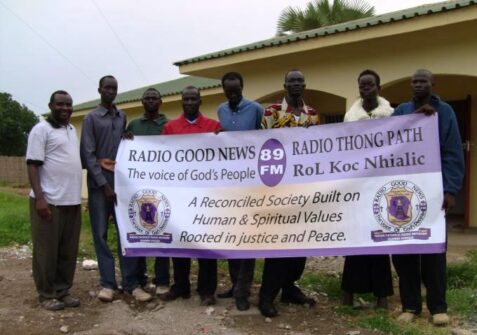

The Catholic Radio Network of South Sudan and the Nuba Mountains (CRN) is a network of nine community radios (Bakhita Radio, Juba; Radio Voice of Peace, El Obeid; Radio Emmanuel, Torit; Radio Saut al Mahaba – Radio Voice of Love, Malakal; Good News Radio, Rumbek; Radio Easter FM – The Voice of Truth and Love, Yei; Radio Anisa – The Voice of Truth and Peace, Yambio; Voice of Hope, Wau; Radio Dom Bosco, Tonj), that reach more than seven million people.

“The original idea was to have a medium-wave station broadcasting from Kenya since, at that time, Sudan would not grant us a licence”, explains Father José Vieira, one of the founders of Radio Bakhita. “It was only in 2005, after the peace accord, that we managed to make progress but we abandoned the idea of the medium wave due to the intense heat during the day. We had to broadcast in the mornings and in the evenings so we decided to create a radio network in each of the dioceses of the South and in the Nuba Mountains, an area occupied by the SPLM-N rebels”, (North Sudan Liberation Movement). After a feasibility study carried out in 2005, training was begun for young people, many of whom had been in the refugee camps in Uganda and Kenya.

At first, Radio Bakhita consisted of just “two containers, one parallel to the other and joined by a wall. The one on the right housed the broadcasting studio and the one on the left the editorial office; between the containers there were some desks used in making programmes”, Fr. Vieira explains. “It really was a rudimentary structure”.

Afterwards, soundproof studios were built in cement. “We went on the air on Christmas Eve 2006, experimentally, but the first proper official broadcast was not made until the day dedicated to the first Sudanese Saint, 8 February 2008, Saint [Josephine] Bakhita’s Day”. The woman who was once a slave was canonised by Pope John Paul II in 2000.Today, the entire network of nine stations, each with ten to fifteen journalists, is the property of the Episcopal Conference of South Sudan.One of the great qualities of the network consists in having been able to utilise synergy. “We organised news programmes covering the whole of the country at practically no cost, since each one shared whatever they had”.

Another policy that gained the support of the public was to broadcast in different languages. The ten million inhabitants of South Sudan belong to 64 ethnic groups (the largest of which is that of the Dinka, followed by the Nuer, Shilluk, Azande, Bari, Kakwa, Murle, Mandari and others) and they speak more than sixty languages. Radio Bakhita, for example, based in the capital Juba with its ‘multilingual journalists’, broadcasts in English, Simplified Arabic, Bari, and Dinka; the other community stations broadcast in Tira, Otoro, Lera, Muru, Otuho, Madi, Acholi, Didinga, Topasa, Shiluk, Nuer, Balanda, and Zande.

Speaking of The Catholic Radio Network of South Sudan and the Nuba Mountains (CRN), the general director of the Network Mary Ajith notes, “It is founded upon four pillars: evangelization, information, education and entertainment”. “We continue to open the broadcasts with the Rosary and Morning Prayer followed by news and various other programmes. The programmes with most listeners are Holy Mass and those concerned with peace-making. In uncertain times, people want to know if their villages, many of which are very remote, are safe and sound and the radio is often their only means of communication”.

“Censure and insecurity are our greatest challenges but we do not spare ourselves”, insists Bogere Charles Mark Kanyama, 35, director of Radio Bakhita, a station that has more than a million listeners and has a range of 300 km. “In 2015, our station was shut down simply because one of our journalists had spoken with Riek Machar, the then leader of the opposition”. “The popularity of Radio Bakhita is due to the fact that it is the only radio station that is concerned with social and political questions”, says the director. “Today, censorship prevents many journalists from operating freely. As a Church institution, we cannot refrain from creating forums where people can freely express themselves”.

Radio Ditunga

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a country ravaged by years of armed conflict, food insecurity and various epidemics – cholera, measles, Ebola and now Covid-19 – a radio station in the province of Eastern Kasai seeks to bring ‘holistic comfort’ to its listeners as described by its founder and director Father Apollinaire Cibaka Cikongo.

“Ditunga Project [PRODI] is a non-profit association founded in 2006. The homonymous station began broadcasting on 17 July 2010. It is on air, without a break, from 5:50 to 23:00, in Chiluba (80%), one of the four national languages of the DRC, and the most widely spoken in Eastern Kasai, and in French (20%).

Thanks to “the altitude – 805 metres – and powerful transmitters”, Radio Ditunga, with its sixteen journalists both local and national, may be listened to within a range of 350 km.

Radio Ditunga began broadcasting on 17 July 2010. It is on air, without a break, from 5:50 to 23:00.

Father Cikongo estimates that the area has about 5 million inhabitants. Over a period of eleven years, the station “reinvented itself in fidelity to its ecclesial and community identity. We have succeeded in creating a series of programmes that correspond to the expectations of the complex and heterogeneous public”.

No subject is taboo, says Father Padre Apollinaire Cikongo, who leads a Sunday programme in French and Chiluba in which he tackles “all the social and actuality questions”.

The important role of the Cikongo radio station became evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, especially in 2020, with all the social distancing measures. For three months, it was the primary and secondary school for many students, a school of health and hygiene but most of all a connecting link between communities and the chapel for Catholics and non-Catholics alike”. “It is not easy to work freely” in the DRC, states Father Apollinaire Cibaka Cikongo.

“In the past, it was common for us to be interrogated by the local and provincial authorities and the security services. There was, at its worst, danger during election campaigns with the threat of closure or death directed against one or other of the journalists. We are thankful to God that they were nothing more than threats and intimidation”.

The Radio is part of a great project that includes agricultural cooperatives, schools, and health centres. Father Apollinaire Cibaka Cikongo concludes: “Ours is a dream in which no human being is illiterate or at the mercy of destruction caused by ignorance, superstition or manipulation; a dream in which all human beings, fully responsible for the political destiny of their villages, enjoy their rights and duties”.

Margarida Santos Lopes