South Africa. Second-Hand Books Take Over the Johannesburg Literary Market.

Johannesburg, often associated with skyscrapers, insecurity, crime, begging, and in some areas, difficult access to basic services such as electricity or water, boasts more than 10,000 street stalls and shops selling books.

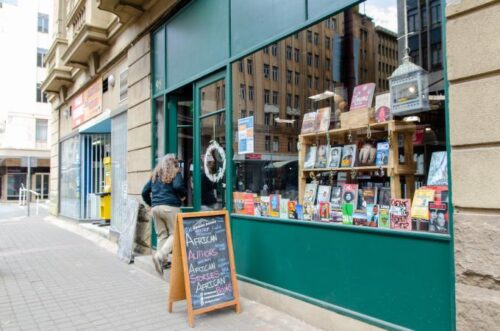

The Bridge Books bookstore, characterised by a wooden door, is located at 98 Commissioner Street, a major street in the Central Business District of Johannesburg, where one can admire the imposing Carlton Centre, the second tallest building in the continent.

Bridge Books is always crowded with university volunteers doing inventory, with young people patiently waiting to be assigned the tasks of the day, and with the small groups of foreigners who before the pandemic were tourists and who today are only expatriates working in the country for embassies or private companies.

Johannesburg informally known as Jozi, Joburg, or “The City of Gold”, is the largest city in South Africa.

Griffin Shea welcomes people visiting the bookshop offering them a drink. This jovial and enthusiastic American, who first visited downtown Johannesburg as a young journalist a decade ago, was struck by the intensity and harshness of this place and decided to stay. He enrolled in a creative writing course at Wits University, and finally in early June 2016, he made his dream come true, and opened his own bookstore, Bridge Books. A journalist and writer who turned book seller. This big change in his life was the consequence of the long time spent walking through the centre of Johannesburg talking with the booksellers in the streets and visiting every single bookshop of the city such as Kalahari Books, L´Elephant Terrible or Skoobs -Theatre of Books, where the international and second-hand book market prevails. During his long strolls around the city and conversations with its booksellers, Shea was able to perceive the connection between books and those passersby who walked with their mind immersed in their work and responsibilities.

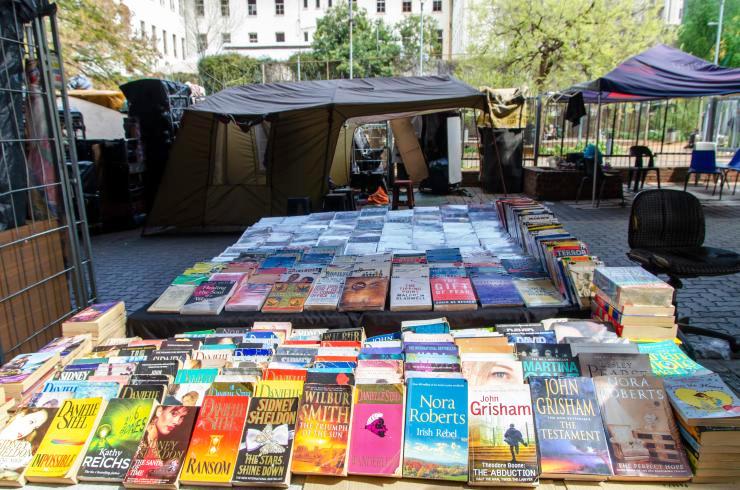

There are more than 10,000 stalls and bookstores where 90% of the books on offer are second-hand and by foreign authors.

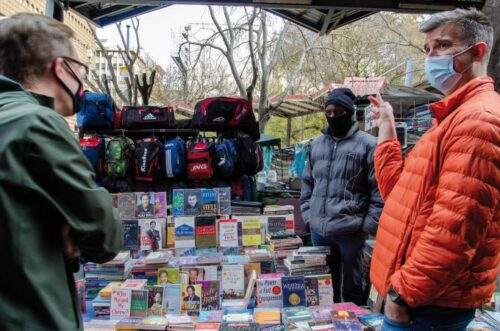

“Here in Johannesburg, there are more than 10,000 stalls and bookstores where 90% of the books on offer are second-hand and by foreign authors. Pocket editions, or second-hand books. Books are part of the needs of passersby”, Shea explains. He spent a lot of time talking with booksellers at Park Station, the central bus and train station located in the Hilbrow neighbourhood, an area where two million people used to pass by on working days before the pandemic. “At the time I was attending the course at Wits University, there was a great debate about the decolonization of literature, and one of the criticisms that was made was about the lack of bookstores in the city centre and in the townships. This is why I began to stroll around the centre of the city and found dozens of people who were selling books in the streets, in markets, or even in hairdresser shops or those shops that sell hygiene products or diapers for babies. I was impressed”.

Shea realised how important was a fictional story for people in order to escape hard everyday life or fantasy narratives to nourish imagination; this made him decide to become one bookseller among those at Park Station. “I quickly sold 20 books, and then many more. I could see that people were willing to buy books as much as essential goods, this made me decide to open a book store”, he adds.

Shea’s project

At Bridge Books, 75% of the books are by African authors, and the international fiction section is relegated to a corner. Thabiso, Shea’s right-hand man in the business, is enthusiastic about his collaboration with the American journalist turned bookseller; besides, Thabiso has proved to be a good bookseller too. He selects books, taking into consideration that the choice of content is what gives the bookstore its identity. He also keeps separated new books from second-hand and old books which are much less expensive.

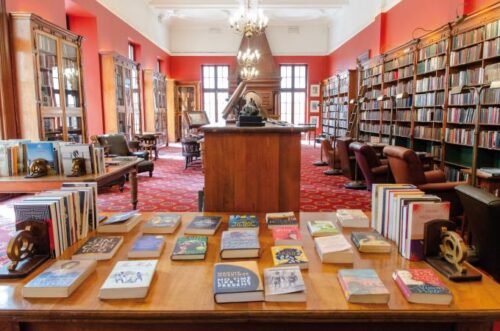

Shea and Thabiso also work as distributors for dozens of street booksellers who do not have access to large publishers and distributors. “We sell customers many old books but also new ones, especially political essays and biographies”, Thabiso explains. The Bridge Bookstore is located very close to the Rand Club, the city’s most enduring social institution and reading club founded in 1887, which has witnessed the most important events of the city. In fact, its construction dates back to the first years of the discovery of the gold mines, and its founder was the British businessman and politician Cecil John Rhodes. “The club has a membership of 600 and today it is representative of contemporary South African society and is open to everyone who shares in its ethos, regardless of gender, race or creed”, comments Shea, while showing the reading rooms and the large library whose book loan registration is still done in writing by hand in a notebook.

Booksellers in Johannesburg are currently suffering the economic difficulties that Covid-19 has caused. “People stay at home, many work from home, we have lost customers who used to come here every day”, says a vendor who sells both second-hand books and clothes at his stand.The National Library located farther down the street contains a million and a half books.

It is currently closed due to the damages to the roof caused by the rains. “It is a splendid place, and it is open to everyone for consultation; it is a pity that what this place offers is not widely publicised. This city is full of smart and creative people who like to read”, says

Shea, who believes, in order to enhance reading, books in South Africa should be published in all the eleven official languages of the country, should reach communities through neighbourhood bookstores and, at the same time, small libraries should be created in schools. “In South Africa”, Shea underlines “people love to read, but there are unglamorous, logistical issues that get in the way of promoting a culture of reading”. Because of this, the owner of Johannesburg’s Bridge Books has launched the African Book Trust, a new non-profit dedicated to donating local books to South African libraries and schools. There is no doubt that the book market is very much alive in Johannesburg, and it adapts itself to the readers of different contexts; books can be sold in stores as well as on a sidewalk. Book markets share space with begging in the streets of Johannesburg. The need for reading is there, at street level.

Carla Fibia García-Sala