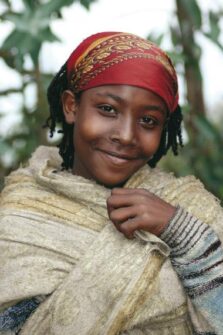

Ethiopia. Maqbasa. Name-giving.

One of the greatest feasts among the Guji – an Oromo ethnic group – is that of name-giving. Like all other great feasts, it is sealed with the sacrifice of a bull, dancing and youthful games.

In speaking of the maqbasa or name-giving ceremony, we must first mention the gadaa system which divides life from birth to old age into ten grades or periods of eight years each. The passage from one class to another implies a new title and new social functions within the group along with the signs and symbols that accompany them.

The celebration of name-giving takes place when children enter the generational class of qarree. In this phase, a collective name is assigned to the children by which they begin to identify themselves with one of the five age-names, robale, halchiisa, harmuufa, dhallana and mudana, which the people call the fincaan Guji (the seeds of the Guji people).

The rite, like almost all other Gadaa rituals, is carried out once every eight years and all the men of generational Gadaa age give a common name to all their children.

The ritual is led by Abbaa Gadaa and involves the killing of a bull, prayers and the performance of popular songs known as qexala.

In choosing the date for the name-giving, it is necessary to make sure it will be an auspicious day.

Starting on the previous day, an altar is built in front of the hut: some branches of a sacred tree stuck in the ground and tied in a bundle. The altar is the place where God will be invoked and the sacrifice will be carried out. The father invites all the neighbours and friends who come with abundant milk and werk as a contribution to the feast. The dancing and singing begin on the previous day and go on all night.

During the ceremony itself, the Abbaa Gadaa wears a small horn full of honey on his wrist and holds a phallic rod in his hand, both of which are signs of fertility. Sitting on a wooden stool, he receives from the mother of the children due to be given a name a pumpkin full of milk together with a bunch of fresh herbs which she places at his feet.

Then, in order of birth, each of the children receiving a name lies in front of him. Abbaa Gadaa, in full view of everyone, pronounces the following sentence: “I give the name to my children”, as if they were his own. They all answer in unison: “May he hear you and may you lead many animals to pasture”. The Abbaa Gada shaves his children, leaving a small quiff of hair on their heads. This upper part that is not shaved off is called qarree, which literally means ‘summit’. The shaving is followed by a speech by the Abbaa Gada who repeatedly says: “I am naming my children, listen to me “. The public answer saying: “We have heard”.

The Abbaa Gada then calls the children by one of the names of the Guji age series, according to the child’s age. If the age-group to which the child belongs is mudana, the name of his children will be robale which means five age-groups (40 years) after him. When the Abbaa Gada calls the name, robale, for example, the public repeat the same name. As a result, the same name is given to all the children of men belonging to the same Gadaa generation.

The sacrifice

All then go to the cattle enclosure which is built of bamboo poles a few metres from the hut. Abbaa Gada gives a long blessing, oiling the enclosure and its entrance with butter; holding the phallic rod over the animals he asks that they be protected from all evil, that they may grow healthy and fat and multiply. They then walk slowly back to the hut and drink the milk from the pumpkin.

Now, it is the tonsured children alone who, bare-breasted, take the bull from the enclosure and bring it close to the altar of branches in front of the hut. Abbaa Gada greases the animal with butter and passes a stick over its chest while praying: “Give us peace. Keep my cattle healthy. Let them grow and fatten. Let me live with them. May I be saved from all evil. May he live in peace and grow old”.

All the participants, in hierarchical order, pronounce the same words, passing the palms of their hands over the chest of the victim. The women do not take part or pray but sing and dance in the hut.

The bull is tied and thrown to the ground, its head is turned and the horns are stuck in the ground. The Abbaa Gada brushes the whole neck with some fresh herbs as far as the front armpits where he fixes them. Then, with a lance with some leaves on its blade, he pierces the windpipe of the animal. Those who have been given a name open both cheeks with knives. The lance of the Abbaa Gada completes the cut in the neck and the blood flows into a skin without falling on the ground. Some is collected in a container to purify the huts and enclosures of all those who have received a name.

Before anointing himself with a wooden spoon full of butter, the Abba Gada opens the entire throat of the animal. Then, placing their hands where blood is still flowing, he and all the participants in hierarchical order apply it to their heads. Strips are taken from the skin of the lower abdomen for those who have been given a name, to be placed on their heads like crowns, signs of good fortune.

Feast

The sacrifice is followed by the feast. Songs of qetala (war) are sung around the sacrifice and the tree with lances on their shoulders, moving at a very tranquil pace. The meat of the victim is cut up and boiled to be served at a common meal where the men sit on one side and the women on the other. A large quantity of local beer is drunk.

After the meal, the songs may continue separately, with the men on one side of the hut and the women on the other. The men dance in close lines, each one with his arm on the shoulder of the man nearest to him. They sing, answering a soloist with a very deep voice and striking the ground rhythmically with the right foot. The sound they produce is similar to that of a stormy afternoon or the roaring of lions.

The women, their heads greased with abundant butter that flows down on their faces and necks, dance in a closed circle, singing songs that mention cows, children, husbands.The ceremony ends with the men withdrawing to a valley where the younger ones challenge each other at wrestling, the only prize for which is the applause of the exclusively

male spectators.

Joseph A. Beekan