Language, the way for Advocacy too.

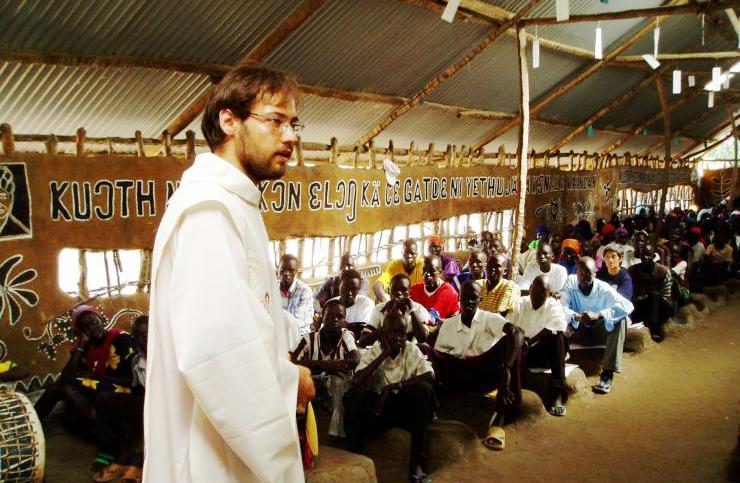

I arrived among the Nuer in November 2005. It was my first mission assignment. I had expectantly waited for that moment throughout many years of training. Now I was there and my first concern was learning the language. I did not hide my trepidation: it was my first non-European language.

My confreres were very helpful and they were a continuous point of reference for me. I made friends with many Nuer youths who endeavoured to teach me their language. Every day I spent hours under the trees conversing with those lads. They loved the publications-project of the Summer Institute of Linguistics: A modern reader in the Nuer language that started in 1982 through the fifth edition in 1994.

They made me repeat sentence by sentence hundreds of times. I was also following the thirty-eight lessons of the pedagogical grammar edited in the fifties by Ms. Eleanor Vandevort, an American evangelist who resided in Nassir from1949 to1963. I was constantly referring to the Nuer – English Dictionary by Fr. John Kiggen, a missionary of St. Joseph’s Society and I treasured the 1933 Outline of a Nuer Grammar of the Comboni Missionary, Pasquale Crazzolara.

Nuer people are very proud of their language and culture. They refer to themselves as Nɛy ti naath – the People among peoples – and call their language Thok naath – the tongue of the People-, setting it apart from the other idioms they called the tongue of Dinka or the tongue of Schilluk and so on. A Nuer proverb says Thilɛ thok gua̠ndɛ – a tongue does not have owners, meaning that a language belongs to everyone who uses it. Therefore, Nuer people are very proud to hear other people speaking their language, and the language is the only necessary entry door to become part of their people. Not only that, another Nuer proverb says Thi̠i̠k we̠c ɛ ji̠kɛ – People are the door into the country. However, they do not make it easy for anyone to enter. It is exceptional to find a Nuer who provides a teaching on language for a foreigner, besides the fact that few have the expertise to present the language systematically with proper grammar, syntax and structure explanations.

I started with great enthusiasm. However, I soon realized how arduous Nuer was. I would easily confuse one monosyllabic word from another. I would not hear the different intonations of the seven basic vowels that would produce about eighteen different sounds and many diphthongs. I feared I would never manage to own that language but I persisted in my commitment and the pastoral work helped me a lot. Studying their language, I was getting closer to them and little by little, I was winning their sympathy. The language at the beginning was a barrier; suddenly, it became the means to build up relationships. I became aware how important listening was especially to the Church leaders and catechists with whom I was spending most of my time. Their way of expressing was so different from mine! They helped me to break through my European mind-set and getting closer to a Nuer mind-set.

A language is not only a number of expressions. Any language expresses also the mind-set and culture of the people using it.

Therefore, mastering a language means owning also the culture and mind-set of a people.

Learning the Nuer language, I got interested in their oral literature. It is so rich with songs, proverbs, riddles, tales and myths. It carries a wisdom that oriented the behavior of so many generations. Many times oral literature, being part of traditional society, holds to conservative values and fears transformation. Other times instead it reveals what people and society need to change. This is the point of encounter with the Gospel, which is always change-oriented. Why should a missionary engage in collecting and preserving the oral literature of a people? Could he not simply replace it with the Gospel narratives answering in a more appropriate way to the modern challenges of a given society?

Well, evangelization is not just replacing old clothes with new ones. Missionaries should be sensitive in respecting the identity of people they evangelize. The language and the oral literature are the vehicles of the culture and the identity of each ethnic group. They shape the way the people think, they fix values and orientate patterns of behavior. There are certainly parts of traditional society, which hold to conservative values and fear transformation.

Actually, continuous changes press on a society, often undermine the identity of the people and provoke a void sub-culture. The need to hold onto solid roots is great. However, change is sometime unavoidable and in some cases, it is most needed. The challenge is about making the right steps, promoting a transformation that is deeply rooted in the identity of the people.

While the Gospel is always change-oriented, it does not throw away the old for the new, it rather promotes a transformation from within the culture re-interpreting it in the new context, both at social as well at spiritual level.

The Church has a special mandate to promote both an interethnic Christian identity and a positive identification with one’s own culture. In fact, those who feel that their language and culture are under-estimated tend to see diversity as a threat, fear changes and under some circumstances might react violently. Those instead who are well rooted in their own culture are also more capable to create cross-cultural relationships. Conflict in South Sudan has often erupted from little understanding, false communication, poor esteem within communities fueling deep frustration.

For this reason, language is deeply relevant also in the advocacy process. To empower people to defend and strengthen their human and social rights, it is not enough to be able to exchange properly experiences and ideas; there is a need also of talking the language of people which their narratives, imaginaries, worldview and mind-set.

Daniel Comboni passionately cried out Africa or death in his attempt to regenerate the people of Africa.

Likewise, people committed in advocacy, grasping how identity of a given people is deeply rooted on their language and culture should build any sincere dialogue in a boldly statement: mother tongue or death!

Father Christian Carlassare,

Comboni Missionary in Moroyok

South Sudan