Colombia. The Wayúu. The spider taught them how to weave.

In the northern tip of Colombia and Venezuela, an indigenous ethnic group has survived, proud of its artisanal tradition. From one stitch to another, this is the textile culture of the desert.

According to the myths and traditions of the women of the Wayúu community, settled in the Colombian department of La Guajira, on the border with Venezuela, it was the walker (the spider) who taught them to weave. It is an ancestral craft whose knowledge is closely linked to the initiation rites that adolescent girls of this indigenous ethnic group must perform to become women.

In the “confinement” ritual, to which all Wayúu girls adhere for months – and in some cases years – and which begins with the arrival of their first menstruation, they learn from their mothers, grandmothers and maternal aunts, the values of their culture and the tasks necessary for maintaining the home. Among these, the most important is undoubtedly the art of weaving.

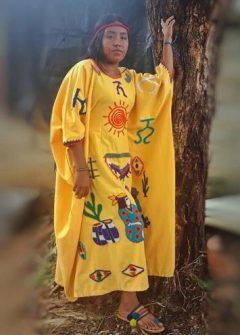

A young Wayúu woman wears her colourful clothes. CC BY-SA 4.0/Neima Paz

The technique and designs with colourful geometric figures, characteristic of this traditional manual weaving, manifest Wayúu art that is passed down, from generation to generation, in this community with a matriarchal structure. Once they have learned the artistic craft and the principles and norms of their society, the young Wayúu women emerge as majayut (young ladies), ready to face adult life in their rancherias. These are located around the most important urban centres of the department of

La Guajira, such as Riohacha, Uribia, Barrancas, Nazareth, Maicao,

Manaure and Bahía Portete.

In their colourful kanás (drawings), the Wayúu textiles, made with needle and thread, represent what these indigenous people experience in their daily lives and elements of their natural environment: the universe, flowers, animals and, of course, their thoughts.

Wayúu bags. CCC BY-SA 2.0/Tanenhaus

The more complex and elaborate the figures, the more valuable the artisanal piece becomes. The Wayúu women make hand hammocks, backpacks, mats, and sandals. Chinchorro fabrics and the hammock are the most representative of this culture.

And although these pieces fulfil the same function, at a textile level they present marked differences: the first is elastic and loosely woven, and the second is heavy and compact, made of palletised fabric. But, without a doubt, backpacks – called susu in the Wayúu language – are today the most appreciated Wayúu product in the national and international market. They are crocheted or knitted in cotton or maguey fibre.

A single indigenous craftsman makes each backpack with their design and its fabric is circular and compact; it can take 20 to 30 days

to finish a backpack.

Wayúu women are dedicated to weaving as a traditional and commercial activity /CC BY-SA 4.0/galakuasth

Wayúu blankets, the traditional dress of Wayúu women, also enjoy increasing success. They are made with light fabrics such as cotton, silk, or printed terlenka. The traditional blanket is square or rectangular in shape, has an oval neck, and has a cord sewn from the inside on the front that holds it at the waist; this cord is knotted at the back, where the fabric is completely free. (Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0/AteneaSGP)

Pedro Santacruz