Gambia. The enigma of three countries in one.

The lack of a government agricultural policy, the impact of imports, fishing agreements and climate change all have a direct impact on Gambians’ diets. Local initiatives to increase fruit and vegetable production aim to address these issues. Three young Gambian women are working on a fertiliser that will improve the country’s

agricultural opportunities.

Almost all of a country’s politics can be summed up in a plate of food. When it’s full, everything is seen in a better perspective. If it becomes empty, nerves set in. But if the mechanisms to fill it are lost, political instability sets in and, eventually, with the exhaustion of hopes for change, flight. In every country, food is usually a brief summary of its history and available resources.

The Gambia River flows through the country of the same name, a strip of land inland from Senegal, on the coast of West Africa. Half a century ago, most of its inhabitants could feed themselves with rice produced in the smallest country in continental Africa. Fish was abundant and was used to prepare recipes such as bennekinno (rice with fish); Peanuts, a crop imposed during the time of British colonialism, gave rise to domoda (rice with peanuts and meat).

Traders at the fish market in Gambia. Fish is becoming more expensive due to the fishing treaties signed with the EU and the arrival of Chinese ships on the country’s coasts. CC BY-SA 4.0/Thukuk

Today these dishes still exist, but it is increasingly difficult to prepare them: only 10% of the rice consumed in Gambia is produced in the country; the rest is imported.

Every increase in the price of petrol, which affects transportation, translates into an increase in food prices in Gambia. Fish is becoming more expensive, also due to the fishing treaties signed with the EU and the arrival of Chinese ships on the coasts of the country. The presence of fishmeal factories, including Chinese-owned ones, which take supplies from the local market, completes an equation that makes life difficult for Gambians. Even vegetables, in a country of farmers, have become inaccessible as a garnish for meals. More and more inhabitants of the country are trying to emigrate, and the numbers prove them right: 28% of the national GDP comes from remittances sent by these migrants, the real lifeboat of an economy where a bag of rice costs more than 30 euros – and the most common monthly income in the informal economy reaches, with a bit of luck, 100 euros.

From Left: Rose Mendy, Veronique Mendy and Sandren Jatta. Photo: Jaume Portell Caño

Rose Mendy, Veronique Mendy and Sandren Jatta, however, do not even consider it: “I would go abroad just to study,” says the first. They met at university, where they studied Agriculture in the same class, and their minds are full of ideas that they want to implement in Gambia. All three work in centres and companies related to what they studied, but their real ambition is to create their own project where they can apply everything they learned at university and in their first job.

Production and food

“I come from a family of farmers, rice growers. At university I learned the techniques that were used to advise my family,” says Sandren Jatta. Born in Berending, she went from being one of the daughters who helped out at home to advising her parents on which techniques to adopt to improve production. She currently works with Rose Mendy, her university classmate, at the National Agricultural Research Institute (NARI), an institution that depends on the government of Gambia.

The goal of NARI is to use different techniques and cultivation methods to increase productivity and, once the results are achieved, share this knowledge with the farmers of the country.

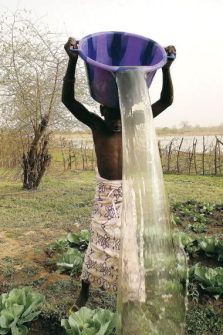

A young boy watering his vegetable garden. “What we produce will influence what we eat” File swm

It is not an office job. Mendy, Jatta and their colleagues spend entire days during the harvesting phase, transporting dozens of kilos of onions and then measuring which experiments have been the most productive: “Many people think that agriculture is a job without prestige, which is why they advised me against it. I studied finance to work in a bank, but the countryside has always interested me”, says Mendy, born in Albreda, on the banks of the Gambia River. His family also grows rice. “What we produce will influence what we eat”, adds Jatta.

In the shops of the country, there are almost no products made in Gambia, apart from bottles of mineral water and cashew nuts packaged in plastic bags. In the markets, a large part of the fruit and vegetables are imported: oranges and apples from South Africa, tomatoes from Morocco, potatoes from the Netherlands or bananas from the Ivory Coast sum up the prospects of a country with almost no industry and stagnant agriculture.

Alternatives

Two figures summarize one of the structural problems of Gambia. Since its independence, the cultivated area has increased very little (9% in 57 years). In that period, the population has multiplied sixfold. The decline in the use of fertilizers has reduced the productivity per hectare of key crops such as rice. This situation has accelerated a demographic change: the movement of the population from rural areas to cities and peri-urban areas. In other words, there has been a rural exodus that has led hundreds of thousands of people to go from being producers to consumers of food.

The failed agricultural policy has created three countries in one: rural Gambia, urban Gambia and the diaspora. Rose, Veronique and Sandren, born between the late 1990s and early 2000s, fit into this perception, in this case through their studies: “When you want to go to university you have to go to urban areas. There is nothing like this in rural areas, so you have to come,” says Rose.

A view of the city of Banjul. “When you want to go to university you must go to urban areas”. Pixabay

Climate change is another of the obstacles that Gambia’s primary sector faces, as explained by Sandren Jatta. For her, four reasons explain the reduction in some harvests, and two of them have to do with global warming: increased salinisation and the lack of rain: “It doesn’t rain but when it finally rains, the amount is very low,” she laments. And she adds that, sometimes, if livestock is not well monitored, the animals can eat part of the harvest. The lack of fertilizers – or their improper use – completes the picture: “Fertilizers are expensive and many people don’t have access to them. Before, farmers were helped more, they received free seeds; now many don’t have them and are subsistence farmers, they don’t have access to education and they don’t know how to use chemical fertilizers optimally and sometimes they apply too much.”

Veronique Mendy is the one who knows the world of fertilizers the most of the three. She works for a company that uses a formula that is perfectly suited to the situation in Gambia: it fills drums with old fish and mixes them with water, garlic and limestone to transform them into fertilizer. According to Mendy, fertilizers are at the heart of the problems of Gambian agriculture: “There are those who don’t have land, but have water; there are those who have water, but no technical knowledge, or are attacked by insects”, she comments.

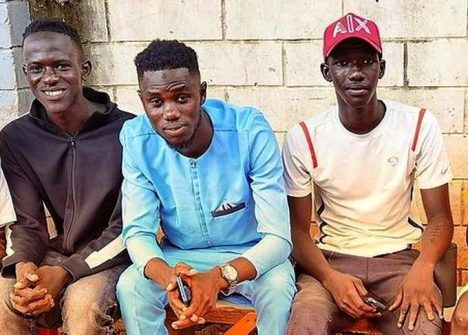

Young People. “We must encourage young people to go into agriculture. ”CC BY-SA 4.0/DWreporter

And she smiles, proudly, announcing what she is working on: “What we are preparing serves as a fertilizer and an anti-parasitic. The costs are very low and the goal of the team she works with is to produce fertilizers that are cheaper than imported ones. Mendy lists the prices of raw materials: “The fish comes to us for free or almost; The rest does not cost more than 200 dalasi (less than three euros) to make a 50-kilo bag. “We should add the costs of transportation and energy to produce it.” According to her, if they managed to commercialize it, this ingredient could revolutionize Gambian agriculture: considering that a bag of fertilizer costs 33 euros, for the same price Gambian farmers could get several bags of local fish-based fertilizer.

Overcoming obstacles

Many Gambians do not trust products made in Gambia. “Gambians often prefer imported products,” Veronique Mendy notes. But she trusts the product she is learning to make to overcome this reluctance, and she trusts especially the youth: “We must encourage young people

to go into agriculture.”

The Gambia. Women at the Market. “Gambians often prefer imported products”. Pixabay

They want to combine horticulture – Rose and Sandren’s strong point – with livestock farming, which would be used to produce fertilizer – Veronique’s strong point – with manure. Her goal is to achieve the greatest possible self-sufficiency, importing only items that are not produced in the country. At the moment, they are looking for capital to start their investment: “They are helping us to cultivate a hectare and, in our case, we don’t need to hire an expert to advise us: we can do it ourselves,” explains Veronique Mendy. The goal of the project should be combined with other measures such as improved storage and a more stable electricity supply.

The three young women are looking forward to this and other projects. Because they believe that solutions must be found locally. This is surely a way to help many young people to stay and invest their energies in their own country. (Open Photo: The Gambia. People and fishing boats on one of the beaches of the coastal town, Tanji. Istock/Salvador-Aznar)

Jaume Portell Caño