African art and sense of beauty.

When you look at some African art, you may wonder whether what you see is fine art or something else. African scarification is part of African art, which is mainly iconographic. In traditional African art, colours are not only used for aesthetic purposes. They have deep meanings. African art is functional, community-orientated, depersonalised,

and contextualized.

Many tribes in Uganda and elsewhere used to practice scarification on the bodies of their women, children, heroes and candidates for initiation. Some went so far as to remove the front teeth of the lower jaw. In the Oromo valley of Ethiopia, you can still find Mursi women with lip plates: the lower lips are stretched to unbelievable proportions to accommodate the lip plates – all in the name of beauty and identity. What some would call ‘disfigurement’, others would call ‘beautification’.

In the Luo languages there is the same word for both beautiful and holy: ‘leng’ can mean holy or beautiful.

In Ateso, the word ‘elai’ can mean both beautiful and good: elai apese means ‘beautiful girl’, but ‘elai eketau’ literally means ‘beautiful heart’, simply referring to a good person. These few examples suggest that beauty, goodness and holiness are closely related.

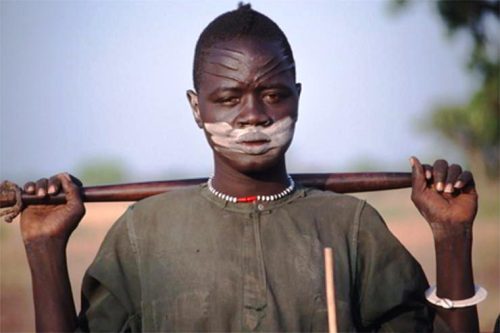

South Sudan. Dinka man. African scarification is often related to the spiritual world. File swm

African scarification is part of African art, which is mainly iconographic. Iconography is a system of images used by an artist to convey a particular meaning. It is often related to the spiritual world. It expresses the supernatural powers to which Africans owe their existence and on which they recognise their dependence.

In Africa, works of art, whether visual, poetic or musical, are used to convey the unknown in the familiar, the abstract in the concrete, and the spiritual in the physical. They are designed to serve a practical and meaningful purpose; beauty of appearance is secondary. African art is therefore functional. We can even speak of ‘functional beauty’. It responds to needs that are vital to the spiritual and physical well-being of the people.In traditional African art, colours are not only used for aesthetic purposes. They have deep meanings. Red symbolises vitality and life force; yellow represents spirituality and kingship. Green embodies nature and fertility, while blue signifies protection and spirituality. White is the colour of ancestral spirits.

Black represents power, authority and the invisible forces of the spiritual realm. Sometimes it also represents the earth, humanity and the ancestors. Unlike Christian liturgy, where clergy wear coloured robes, in African worship colours are painted on the bodies of those who participate in rituals. In ritual, the physical and the spiritual are one.

Ethiopian young Ladies. “Functional beauty” is a response to needs that are vital to people’s mental and physical well-being. File swm

A curious fact about African art is that it is depersonalised. Traditional artists do not sign their work. It belongs to the people and not to the artist, although his creativity is inevitably present in his work. It is community-oriented in that the artist performs to fulfil the ritual and social purposes of the community.

Art is used to regulate spiritual, political and social forces within the community. This is particularly evident in Malawi (Chewa), the Democratic Republic of Congo (Pende) and Nigeria (Igbo and Yoruba), where masks or masquerades play an important role in festivals, rituals, funerals and other social gatherings.

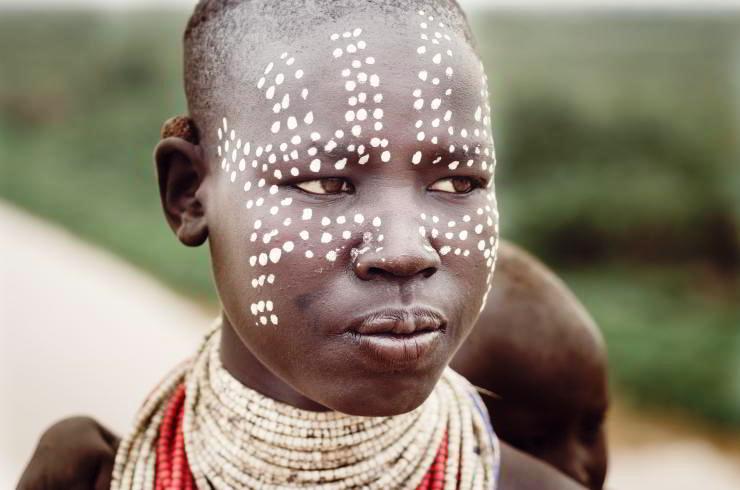

They represent human and animal spirits, deities, ancestors, mythological creatures, good and evil, peace and justice, etc. Sometimes the people who wear them are believed to be possessed by the spirits they represent. They also carry messages and teachings from the spiritual world.Finally, African art is functional, community-orientated, depersonalised, and contextualized. (Open Photo: Karo woman. Kar. people are famous for their body painting. 123rf)

Edward Kanyike