South Africa. A Rainbow nation that needs to be reinvented.

The loss of the absolute majority by the African National Congress (ANC) is the most serious setback in the region for a movement that led the wars of liberation against white regimes. Could something similar happen in neighbouring countries?

The South African elections last May marked a turning point in the history of Southern Africa. The end of the solitary rule of the African National Congress (ANC), which for the first time since 1994 lost its absolute majority and was forced to seek agreements with other parties to form a coalition government, represents in fact the first shock to the balance that had lasted since the end of the Cold War.

Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa since 2018. Photo: Simon Walker

In almost all the countries of the region, the 1980s and 1990s had seen the birth of democracies characterized by the domination of parties born from the transformation of liberation movements against white regimes. With a series of peaceful transitions and “free and fair” elections, Swapo had come to power in Namibia (1990), MPLA and Frelimo had seen their governments legitimised in Angola (1992) and Mozambique (1994) and the ANC had taken power in South Africa (1994). In all these cases, movements that had pursued an armed revolution and had threatened to move the region into the Soviet orbit had been protagonists of an unexpected reconciliation with the capitalist West and the liberal model, in which the liquidation of segregationist regimes had been exchanged for the abandonment of Marxist-inspired economic reconstruction projects.

Under the stabilizing rule of these parties and the absolute majorities they obtained at the ballot box, regimes emerged that reconciled what had seemed irreconcilable. On the one hand, the fundamental rules of the market economy, starting with property rights, had been confirmed, and a model of civic-liberal citizenship had been established that was capable of preventing the expulsion of minorities and of stemming the “tribalistic” tendencies that had dominated the scene in the rest of Africa.

Nangolo Mbumba, president of Namibia. He is a member of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). Photo WIPO.

On the other, the de-racialization of the state and the economy had encouraged the formation of a large black middle class, which had taken control of the public sector and placed white minorities at the top of the social pyramid.

It is true that the success of the liberation movements in keeping the new emerging elites and the poor masses united under their banner made it difficult to imagine an alternation between majority and opposition.

However, their monopoly seemed to be compensated for by their strong integration with the centres of the global economy – which served as a guarantee for the rule of law and the independence of the media, the judiciary and the private sector from political power – and by the demonstrative value of the new regimes, which seemed to embody the possible conciliation between the aspirations born with the liberation from colonialism and participation in the liberatory order and the globalized economy.

Inflexible Power

The model began to show the first cracks during the 2008 global crisis. In the following years, the reemergence of populist demands and the growth of corruption, involving all the parties in power in the region, began to wear down the image of the democracies of Southern Africa and in one case (Zimbabwe) led to a serious crisis of legitimacy of the government born from the liberation struggle.

A township on the outskirts of Pretoria. File swm

The media and observers identify the decline as the cause of the lack of alternation at the top of the state, aggravated by the legacy of “democratic centralism” that characterizes movements built on the Leninist model and incapable of fully accepting the logic of pluralism and the “open society”. However, it is undeniable that the crisis also has its roots in the profound malaise that arises from the social inequalities that characterize all societies of Southern Africa. The abolition of racial discrimination and of the correspondence between “race” and “class”, in fact, does not seem to have altered an economic structure that remains based on the coexistence between an urban economy linked to those of the “first world” and the vast periphery in which the majority of the population lives, dependent on the former and much poorer.

South Africa, laboratory or exception?

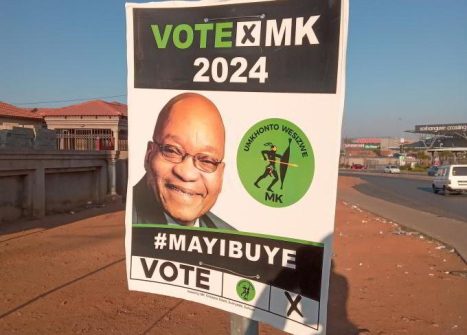

The phase that opened with the defeat of the ANC is linked to conditions that are not easily replicable in other countries in the area. South Africa presents an ethnic-racial scenario that is more suited to forms of “plural” democracy and power-sharing. The size of the white, coloured and Indian minorities (equal to about 20% of the electorate and concentrated mainly in the cities) has in fact allowed the Democratic Alliance (DA), the main opposition party to the ANC, to rely on a stable base and to assert itself in the province of Western Cape, from which it has been able to project the model of a more efficient and less corrupt administration. The strong Zulu identity has contributed to the birth of the MK, the party of former president Jacob Zuma who, by attracting its most intransigent and populist component, has pushed the ANC towards a “centrist” alliance with the DA, on which the new multi-party government is based. Nothing similar is found in other countries, where the tension between Westernized cities and “ethnic” countryside seems more difficult to trace back to the logic of electoral competition and inter-party play.

An MK Party election poster with the face of former president Jacob Zuma. Shutterstock/ Reabetswe C Matjeke

This does not change the fact that South Africa has now become a kind of laboratory for the entire region. The long-term success of the new government will certainly depend on its ability to restore trust in the state and administrative efficiency shaken by scandals and infrastructural failures such as the crisis in electricity production. However, it will also be necessary to rebuild a national cohesion based on a vision of the country that is not based solely on the memory of the struggle against segregationist regimes, inevitably divisive and easily monopolized for their own advantage by the elite of the liberation movements. The fact that, a few months before the elections, the victory of the Springboks, the national rugby team that was always identified with the white Afrikaners, in the World Cup in Paris, was celebrated as the success of a multiracial and multilingual country, could be a first sign of a recovery of the image of the “rainbow nation”, launched in 1994 by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, but set aside during

the years of ANC hegemony.

African National Congress delegates at a conference. File swm

Even more important, however, will be the ability to reconcile liberal democracy and the rule of law with a macroeconomic formula capable of countering the frightening inequalities that continue to afflict South African society (and other societies in the region), also overcoming the limits imposed by the rigid application of the neoliberal model. In the immediate term, the entry of the DA into the government and the negotiations for the renewal of the AGOA, the trade agreement with the US that South African exports cannot do without, should have closed the escape routes towards the dirigiste models embodied by Moscow and Beijing. In the medium term, however, the new government will have to demonstrate that it has better recipes than the populist and radical solutions that important components of the ANC and other parties in power in the area still look to. Otherwise, the survival of democracy and the levels of development in the region are at stake.

(Open Photo: File swm)

Rocco Ronza