Egypt. The long night of the Egyptian economy.

Economic crisis. The burden of foreign debt. Education in collapse. Episodes of xenophobia. The conflict in Gaza aggravates the situation.

Since taking power in 2013, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has focused on major infrastructure projects to establish his power. Over the last decade, Egyptian governments have spent tens of billions of dollars on megaprojects and international events, including the creation of a new capital and the organization of Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022. Although Cairo’s politics had as its first objective the reconstruction of Egypt’s image abroad, with mixed results, the enormous expenditures have had a profound impact on the reality of the country.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. CC BY 4.0/Min. of Communications and Information Technology.

The brand-new road networks south of the capital open onto the suburbs of the Zahraa Al Maadi area. Far from the typical aggregation centres of Cairo, a new and different urban planning model is developing. Under the viaducts, and in the pedestrian areas, cafes and restaurants attract wealthy citizens. But although the new system appears clean, organized and impeccable, it hides the chronic difficulties of the city, and more generally of the country. Some causes of the crisis, not directly attributable to the al-Sisi cycle, date back decades. The lack of industrial development due to poor planning and burdensome bureaucracy, and the export policies that have created a persistent trade deficit, are heavy burdens to carry. Added to these are other chronic problems that Egypt has been with for decades. Corruption, property rights and weak institutions, as well as an overbearing state and military that continue to discourage investment and competition.

The burden of the debt

But al-Sisi’s administration is not entirely free of direct responsibility. The borrowing frenzy that characterized his government, in addition to having left a country with a heavy foreign debt, which grew from around 70% in 2010 to 96% in 2023, pushed the Central Bank to increase interest rates in an attempt to attract new investors and refinance loans, thus generating ever larger deficits.

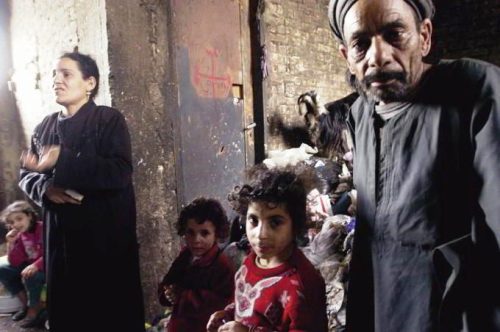

Around 10% of the country’s population has fallen into poverty since 2010. File swm

The result of all this translates into ten million Egyptians – approximately 10% of the country’s population – who have fallen into poverty from 2010 up to today. And while unemployment fell to around 7% in 2024, participation in the labour market also decreased steadily in the decade up to 2020. The litmus test of these phenomena can be seen in the high rate of emigration from the North African country. According to Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouli, in 2023 the number of Egyptians abroad has reached 12 million. Closing the vicious circle is the state of public education – close to collapse. A dynamic that pushes many graduates to look for work outside Egypt.

In an already complicated context, the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have further fuelled inflation. The North African country has therefore turned increasingly eastward, to the other side of the Red Sea. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have become fundamental partners for the stability of Egypt.

Central business district (CPD) in the New administrative capital of Egypt. CC BY-SA 4.0/Mahan84848.

But if on the one hand, loans and guarantees helped the Cairo government avoid default, on the other, great discontent was generated over what it all cost. In the beginning, it was the islands of Tiran and Sanafir, located in the Red Sea and sold to Riyadh in 2016 for 20 billion dollars in investments. Today, at the centre of the Egyptians’ silent murmurings is the 35-billion-dollar agreement between Egypt and the United Arab Emirates for the Ras Al-Hekma area, 200 kilometres east of Alexandria. The project involves the construction of a new city on the Mediterranean coast, a possible tourist centre, in which Abu Dhabi will hold 65% of the property.

Scapegoats

And while the militarization of the Egyptian economy is a long-standing problem that is plaguing the country, on the streets we can see the clear symptoms of a suffering society, while the tensions of those who see no future ahead are projected outward. The main signals come from episodes of racism and xenophobia towards migrants. According to data from the World Organization for Migration (IOM), in addition to the almost 500 thousand asylum seekers, around 9 million people of different nationalities live in Egypt. Sudanese, Yemeni and Syrian passports are the most numerous. As reported by several NGOs and think tanks, cases of violence against these communities are commonplace, while the authorities prefer not to intervene.

Displaced Palestinians set up their tents next to the Egyptian border. Shutterstock/Anas-Mohammed

Episodes of xenophobia are also recorded against Egyptian populations. The Nubians, an ethnic group from the south of the country, endure a fate similar to that of migrants. Considered second-class citizens, they have been denouncing the brutality and repression of the authorities for years. In this context, the Gaza crisis risks triggering a social bomb. Egypt’s dependence on revenue from remittances, tourism and taxes from trade passing through the Suez Canal makes its economy particularly vulnerable to external shocks. The conflict in the Strip is weighing on all three of these revenue streams, making the issue of displaced Gazans in the North African country even more sensitive. But if Egypt’s situation has the typical features of a countdown, there are still those who think that the country, thanks to its position and its assets, has the typical characteristics of being “too big to fail”.

A vision which on the one hand gives a glimmer of hope to the Egyptian government, but on the other hand does not take into account the possible consequences of a further authoritarian spiral and the impact in economic terms on the lives of Egyptians and non-Egyptians alike. (Open Photo: A great pyramid at Giza. 123rf)

Davide Lemmi