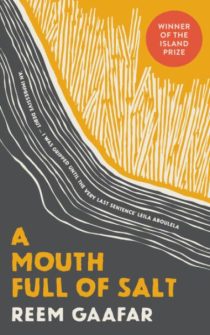

Literature.Three women talk about their Sudan, bitter and divided.

In A Mouth Full of Salt, Sudanese writer Reem Gaafar traces the country’s recent history from a female perspective, shedding light on decades of suffering and abuse.

Rather than news stories, it is often novels that enter into the historical perspectives that help us understand societies better. The tragedies and weaknesses of these societies. This applies to a recent publication. The author is the Sudanese Reem Gaafar who in her debut novel – A Mouth Full of Salt – explores strong themes: racism, intolerance, gender violence, oppressive traditions and female genital mutilation.

Destructive feelings and “habits” that condition life and relationships between Northern Sudanese and Southern Sudanese. And it is women above all who pay the price. The novel tells the life of three of them and through their stories – oscillating between the 80s, then the 40s and then returning to where it all began – it tells of a Sudan that concedes nothing to the female world.

In the background Khartoum, the centre of power and coups d’état, like the one included in the narrative and which concerns Jaafar Nimeiry, his regime and the evil that resulted from it. But back in time, the historical scenario is that of a North and South Sudan colonized by Great Britain and Egypt and considered two separate countries – a policy which, on the other hand, laid the foundations for the subsequent separation.

It is in that context that an encounter occurs between a man from the north and a woman from the south. An encounter that will mark not only their lives but also those of other generations. Nyamakeem does not doubt the words of the boy who stole her heart (love is mutual) nor does she have any reason to doubt the welcome she will receive from his family, there in that village on the Nile in the north of the country. But she is met with violence – first verbal and then also physical – and that mother anchored to traditions who with harsh words puts in order the roles and positions of everyone in society: “… we are Arabs… Ashraaf, our lineage it is pure and uncontaminated and goes back to the prophet Muhammad… There is only Arab blood in it. Even your reckless relatives knew to keep their non-Arab adventures in the dark. That is how it always has been and it must always be so”.

Reem Gaafar is a writer, physician and filmmaker. Photo: HhouseBook

It is with this phrase that the author gives shape to the relationships and civil clashes that for decades – and still today – mark Sudan. After all, that (black, Christian) population was a part of the population “that was always” destined for slavery, for servitude, right in the homes and service of Arab Africans. Then – a 40-year leap – there is Fatima who, unlike the other girls in the village, does not long for marriage but wants to attend Khartoum University, and Sulafa, the mother of a drowned boy, mistreated by her husband and his family because she is unable to have more children. And it is this drowning – as well as other strange, sudden events: livestock deaths, fires – which unites the threads of stories. Yes, because evil generates evil and the past, especially when marked by pain, rejection, and loss, creates a trail, like an underground river, which sooner or later finds a way to return to the surface and drag along those who seemed safe. This is the meaning of the book’s title, A Mouth Full of Salt, a reference to a Sudanese proverb: the taste that remains in the mouth after a great loss.

Antonella Sinopoli