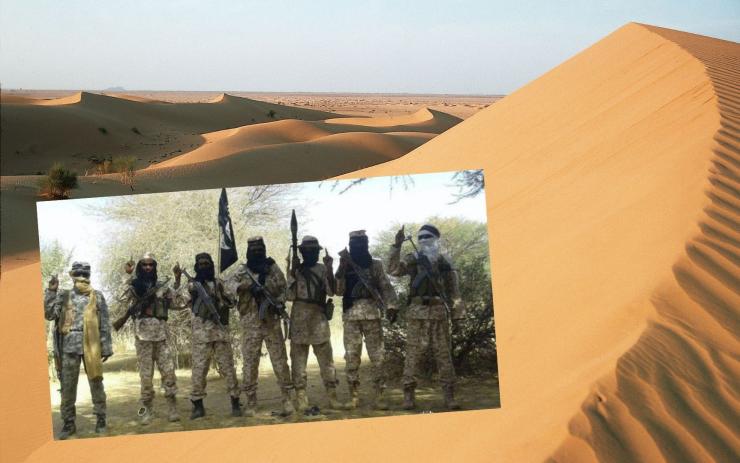

Niger. Jihadists aiming for Niamey.

The most serious threat is that the extremists will expand south and close the access routes to the capital. The military actions of the military junta have so far brought little results. Civilian casualties

have increased.

After the latest coup in Niger, all the countries in the central Sahel region are governed by military juntas and we have therefore entered a new phase of the conflict against jihadist extremism which has been going on for over a decade.Last year Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger also formed the new Alliance of Sahel States (AES) which, as announced in March, will deploy a joint military force to fight against the jihadist cartels that have long been established in the tormented region of three borders,

the Liptako-Gourma.

The military junta led by Colonel Abdourahamane Tchiani, took power in July 2023. ORTN

It is not yet known how the AES will act and how many personnel it will make available, but the new external partners – Russia, Iran and Turkey – raise fears that the approach to terrorism will be mostly security-related and armed. A strategy which, as reported by Human Rights Watch, has already caused serious violations and war crimes against the population in Mali and Burkina Faso, exacerbating the conflict.Some data confirms how the situation on the ground is worsening: half of the deaths from terrorism in Africa in 2023 occurred in the Sahel, where victims increased by 38% and civilian victims by 18% (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project – Acled).

The military junta in Niger (CNSP), led by Colonel Abdourahamane Tchiani, took power in July 2023, justifying his action as “necessary” to take control of a “continuously deteriorating situation” in the fight against terrorism.In reality, according to Acled, the levels of violence and attacks were down by 39% in the country in the first 6 months of 2023 and the coup seems to have instead worked in favour of the jihadists, given that the year ended with an increase of 9% in violence (231 events reported) and victims (48%).

Open fronts

Due to its geographical position, Niger is busy on several fronts. In the north (Agadez region) and in the centre (Tahoua region) it also has to deal with banditry and illicit trafficking with infiltrated al-Qaida cells. To the south-east, in the Diffa region, it has to deal with the Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Boko Haram.

But the focus of the violence is concentrated in the Tillabéri region where the Group for Support of Islam and Muslims (Jnim) and the branch of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (Eigs) are active.

It is in the latter region with long and porous borders with Burkina Faso and Mali that attacks continue to occur. The last one of significant severity occurred last February, and caused the death of 23 Nigerien soldiers in an ambush claimed by the EIGS.

Since the latter terrorist group got the better of the Jnim last year for dominance in the neighbouring Malian region of Menaka, the extremists of the Islamic state have increased their actions in the Nigerien Tillabéri, with strategies more inclined to the killing of civilians and the use of kamikazes. “The most serious threat for Niger is that the extremists, who now have control of the borders in the northwest, also expand to the south and close the access routes to the capital,” says El Hadj Djitteye, president of the Timbuktu Centre for Strategic Studies on the Sahel, as Niamey is located right in the centre of the Tillabéri.

Nigerien Army in the north. They also have to deal with banditry and illicit trafficking involving infiltrated al-Qa’ida cells. Shutterstock/ Katja Tsvetkova

Today the situation may become more complex and fragmented because the Alliance of Sahel states has begun to equip itself with aerial equipment, such as drones supplied by Turkey. It is certainly a point in their favour, but “it pushes the jihadist cartels towards more complex, fragmented strategies and above all towards simultaneous attacks with frequent indiscriminate violence”, explains the analyst. The repeated use of airstrikes leads to an increased risk of targeting civilians and simultaneously pushes armed groups to respond with remote violence (e.g., improvised explosive devices, land mines, mortars and rockets) and suicide attacks, methods which also endanger the defenceless population. El Hadj Djitteye claims that the former Nigerien government of President Mohamed Bazoum had “attempted dialogue with local communities and undertaken rehabilitation and disarmament programs”. For this reason, in his opinion, there had been steps forward, which unfortunately “the military-only approach undertaken so far will cause to vanish into thin air”.

Marco Simoncelli