DR. Congo. New Patriots.

Violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has intensified in recent months. With the M23 rebels occupying more and more space and the United Nations mission (MONUSCO) expected to end before 2025, self-defence groups are increasingly

taking centre stage.

They want arms. They don’t care what sort they are, who sells them to them or where they come from, as long as they end up in their hands. They want weapons to wipe out those hiding on the other side of the bush, but also to save their families and protect their land from the war that is spreading in North Kivu province in eastern DRC. They are the Wazalendo (“patriot” in Swahili), a new local defence militia that has been fighting against the M23 guerrillas since the summer of 2023 and is trying to replace the role of the Mai-Mai militias in the area.

There is no age range or “limit” to being a Wazalendo. In the battalions, retired soldiers mix with young farmers, shopkeepers, unemployed men, mechanics, patriots and girls who are approaching adulthood and who avoid the furtive glances of their companions. At road checkpoints, crowded into positions close to the front and playing cards in the rear, dozens of teenagers are integrated into the militia.

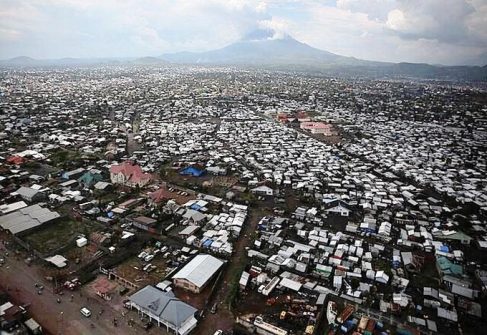

The city of Goma with Nyiragongo volcano in the background. CC BY-SA 2.0/MONUSCO Photos

These militiamen are not part of any government military force and collaborate with the regular army. Wazalendo is the nickname given to dozens of armed groups divided into neighbourhoods, villages and cities that come together with the sole purpose of protecting their land. They put aside their differences to face a common enemy. The neighbourhoods and villages threatened by the M23 have organized themselves, armed themselves as much as possible and are fighting.

This is the case of former general Mbokani Kimanuka, who currently commands 2,780 men and 70 women divided into five regiments. Kimanuka was a military man until he retired to take up farming. But when war knocked on his door, he buttoned up his old uniform and recruited the force that today protects Goma on the slopes of the Nyiragongo volcano. The government asked him to use half of his men to prevent the M23 from conquering the volcano since its summit would become the ideal point for the guerrillas to launch the final offensive against the city. The fighting occurs almost daily. It is Intense, with few victims, but equally mourned by everyone.

The Congolese National Armed Forces (FARDC) are reinforcing their positions around Goma. CC BY-SA 2.0/ © MONUSCO/Clara Padovan

Every loss means the death of a fighter, but also that of a neighbour, a childhood friend, or a brother. The former general states that the very essence of Wazalendo lies in this very human aspect: “We have a strong collaborative relationship with civilians. They are the ones who give us food, water, blankets and wood for the fire to keep us warm. We eat because our women come every day to bring food for us to the base.”

He adds that family and friendship ties between the militia and civilians explain part of their effectiveness. “We are in the front line of battle – he says – and we don’t back down. While the military can fall into the abyss of panic during the fighting, a Wazalendo cannot retreat because he has his home behind him and retreating would mean giving up his home.”

Two waterways

The Wazalendo was born from a double necessity: the inability of the Congolese army to face the M23 in the past two years and the inertia of the United Nations mission in the country (MONUSCO) after almost 25 years from its inception and a few months from its departure from the country. The Wazalendo base their actions on Article 41 of the Congolese Constitution, which states that “every citizen has the right to a healthy, satisfying and lasting environment and must defend it.” The country’s legal framework allows the creation of armed militias, provided that their purpose is in line with the interests of the state and that they do not increase national instability.

Population fleeing their villages due to fighting between FARDC and rebels groups. MONUSCO/Sylvain Liechti

As for MONUSCO, Kimanuka expresses his disappointment by saying that he would like “them to leave Congo” and criticizes them saying “The fact is that they did not fight on the front line with us”. He wants the UN out of his country and is happy that the mission will technically end before 2025. As for the M23, the former general cites Rwandans, Ugandans and ‘white mercenaries’ in the ranks of the M23. For him, this is a war that the Congolese must fight without help because the help that comes to them is often counterproductive due to the interests linked to third countries in the riches of the DRC.

Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi is aware of the risk of entrusting the security of North Kivu to the militias. One of his promises during the election campaign preceding the December 2023 elections was to ensure the integration of militias into the army and to this end he proposed creating a reserve force. Former general Kimanuka agrees, although he believes that it would be more appropriate for the Wazalendo to be integrated into the army at the end of the conflict, rather than

during the course of it.

Shortage of material

To avoid improper use of weapons, militiamen receive very little military equipment with which to engage in combat. When a Wazalendo prepares for battle, he holds his machete close and a sorcerer applies the gri-gri spell that makes him ‘invisible.’

Only one in four uses an AK-47 instead of a machete. They fight and die, win or lose. When the latter happens, enemies flee and it’s time to desecrate the dead. The militiamen can keep the rings and the few banknotes they find during the looting, but the weapons they seize from the fallen are sent to the military authorities who decide how many the Wazalendo are to keep and how many are to be allocated to the state arsenal. Kimanuka states that “there are very strict rules regarding the movement of weapons, especially to avoid abuse. A Wazalendo who misuses his weapons will be tried by a military court, not a civilian one.”

People on the road from Virunga National Park to the city of Goma. iStock/ guenterguni

The Tshisekedi government’s restriction on the movement of weapons would appear to be a welcome measure, but both the former soldier and other militia members interviewed suggest a sense of frustration on their part. The scarcity of weapons among the militias and the government’s control over them hinders any hint of initiative on the part of the Wazalendo. Their offensive actions are limited to those directed by regular army commanders.

“If it weren’t for us, the M23 would already be in Goma. We are the only possible defence; we are the front line.” This is how the former general responds when questioned about the usefulness of his militiamen. The army almost never participates in actions in rural areas and the bulk of the troops are stationed in the cities, awaiting the final attack, if it comes. The militiamen’s motivation is strong, based on land and family, but Kimanuka believes Kinshasa could offer them incentives to make their actions even more decisive. He asks for adequate pay and equipment. A salary, however symbolic, replacing, to some extent, the jobs that the militiamen left to offer their lives for their country. Starting with boots without holes, rain ponchos, food, machete-sharpening stones and above all weapons. Without them, they cannot win the war.

A dangerous game

The DRC government is playing a dangerous game with the militiamen. On the one hand, looking at previous experiences, it limits the actions of the Wazalendo and reduces the flow of weapons in their direction; on the other hand, precisely for this reason, it arouses frustrations among these militiamen eager to liberate their land, but who see their government containing them, imposing deprivations on them. The gri-gri is ‘very effective’ until it is pierced by a bullet. The machete is useful in close combat, but useless during a forest firefight. And the lack of means translates into victims. Losses turn into tears. And the tears of the militias can evaporate, leaving behind a corrosive salt that repeats the history of the Mai-Mai militias.

The United Nations mission (MONUSCO) is expected to end before 2025. UN Photo/Clara Padovan

It can be establihed that the direct culprit for each of the victims would be the M23 guerrilla who fired the shots, but the Wazalendo is starting to understand that there is also an indirect culprit or a culprit by omission: the government.

The promise to integrate the members of these armed groups did not materialize, but it allowed President Tshisekedi to receive the support of these in the presidential elections that led to his re-election.

Eyewitnesses speak of militiamen, led by commanders who have not had formal military training, who often become protagonists of violence against the very populations they say they want to defend. Furthermore, bloody clashes have been recorded between different factions of the Wazalendo. Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu, Metropolitan Archbishop of Kinshasa, recently declared that “Armed groups ultimately become a danger to the population, extorting money from citizens, committing thefts and murders and in the business of illegal trading of minerals extracted from artisanal mines in the area”.

Alfonso Masoliver